Day 42: Kansas City, Here We Come

April 30, 2021

Day 40: From Limestone to Lincoln

April 28, 2021Most recently updated on February 11, 2024

Originally published on April 29, 2021

We’re on our way to get acquainted with Mark Twain, the mighty Mississippi and a famous arch.

First, we have one more high-flying stop in Illinois.

So, we head due west out of Springfield on Interstate 72 to begin today’s journey.

After an hour, we stop in at the town of Griggsville, a community of just 1,000 people whose location between two rivers has caused it some problems over the years.

The first European settlers came here in the 1820s. The early industries were flour milling and pork processing.

The fact that Griggsville sits between the Illinois and Mississippi rivers made it a convenient location when steamboats were a major source of transportation.

However, in more modern times, that locale made Griggsville a haven for mosquitos, especially during the hot, muggy summer months.

The birdhouse tower in Griggsville, Illinois. Photo by Waymarking.

Local residents were concerned about using pesticides to kill the flying insects, so they were looking for an alternative. In the 1960s, J. J. Wade, a local resident who owned a local antenna manufacturing factory, came up with an idea.

He told folks that Griggsville was on the migratory path of the purple martin, the largest member of the swallow family. Wade told his fellow citizens that these birds can eat 2,000 mosquitos a day. The problem is purple martins are notoriously bad nest makers. That’s why they migrate.

So, Wade converted his antenna facility into a bird house manufacturing complex. He made 5,000 bird houses and the residents helped install them around town. The aluminum homes include a 562-unit apartment-like high rise that he put up in 1962.

Now, here’s the thing. Wade’s claim about the purple martins is strongly disputed by bird experts. They say the purple martins eat larger insects such as dragonflies. They don’t eat mosquitos.

Nonetheless, town residents swear their mosquito problem disappeared when the bird houses went up and the purple martins stayed.

So, whether Wade was the town savior or the Music Man, he was undeterred. He continued to produce bird houses and sold his bird house technology to companies across the country.

Wade sold his factory in 2006 to a Chicago entrepreneur. He died in 2007.

The purple martins, mosquito eaters or not, are adored by the residents of Griggsville.

The town is known as “The Purple Martin Capital of the World.” There’s also a short section of downtown street called Purple Martin Boulevard.

Fascinating stuff, but it’s time for us to fly the coop here and continue westbound on I-72.

In 40 minutes, we cross over the Mississippi River for the second time on our adventure and enter Missouri.

The Show Me State is 18th in size and 18th in population with more than 6 million people.

The first inhabitants arrived here 12,000 years ago. The first European explorers passed through in the 1670s. The territory became part of the United States in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.

It entered the Union as a slave state in 1821 as part of the Missouri Compromise that allowed Maine to gain statehood as a free state.

Missouri played a critical role in the westward expansion. Lewis and Clark’s expedition started here. The eastern terminus of the Pony Express was in St. Joseph. The Oregon Trail, the Santa Fe Trail and the California Trail all began here.

The state quickly became known as “the Gateway to the West.”

Missouri is also bordered by eight other states, along with Tennessee the most of any state.

Missouri has a blend of Midwest and Southern traditions and culture that includes barbecue as well as Kansas City jazz and St. Louis blues.

The leading industries are aerospace and transportation as well as food and beverage processing. There is a mining industry for coal, zinc, lead and limestone. It has a variety of crops with 95,000 farms, second only to Texas.

Catching Up with Tom, Huck and Molly

As soon as we cross the Mississippi, we enter our first town in Missouri.

Hannibal, a community of 16,000, is best known as the boyhood home of Samuel Clemens, who wrote such classics as “Tom Sawyer” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” under the pen name of Mark Twain.

The region had some relatively quiet beginnings.

A variety of native tribes lived in the area for centuries. The first European explorers arrived in the 1673. Salt was discovered here in 1819, but the town still grew slowly at first. Only 30 people lived in Hannibal in 1830.

The advent of the steamboat soon changed that. Those paddle boats along with flat boats and other river transports brought commerce and residents to town.

The Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad was organized in 1859 by Samuel Clemens’ father, John Clemens. The railway provided a connection to St. Joseph, transporting mail to the Pony Express. Hannibal was the westernmost point for the railroad until the Transcontinental Railroad was built.

The Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum in Hannibal, Missouri. Photo by Wikipedia.

By 1870, Hannibal was Missouri’s second most populous city and third largest commerce center. Its early industries included pork packing, candle and soap manufacturing, barrel making and timber.

In later decades, the economy was focused on shoe manufacturing, button making and cement. Atlas Portland Cement Company began operations in 1903 and is still in business.

The economy today also includes a General Mills food processing plant, healthcare industries and, of course, tourism.

Most of the visitors come to town to see the various places connected to Mark Twain and his books.

There’s the Mark Twain Boyhood Home and Museum. The exhibits include a typewriter used by Twain, a writing desk, a number of first editions of his novels and the only known surviving white suit that was so symbolic of Twain’s attire.

The museum, which opened in 1912, is one of six properties in the complex, which also includes the Becky Thatcher and Huck Finn homes. The legendary white-washed picket fence from the Tom Sawyer adventures borders the property.

The Tom and Huck Statue in Hannibal, Missouri. Photo by the city of Hannibal.

There’s also a Tom and Huck Statue, which was erected in 1926, that looks out over Main Street.

The Mark Twain Riverboat has been giving tours on the Mississippi River for more than 30 years.

The town also hosts a National Tom Sawyer Days festival in July that include a fence painting contest.

Just south of town is the Mark Twain Cave Complex. Guided tours have been given at the caves since 1886. The site was dedicated as a National Natural Landmark in 1972. The big attraction these days is the signature of Samuel Clemens on a wooden frame that was discovered in 2019. Other well-known folks are occasionally asked to add their signatures.

Hannibal has one other well-known famous hometown resident.

Margaret Brown was born in Hannibal in 1867 and attended grammar school here. Brown was an actress and one of the passengers who survived the 1912 sinking of the Titanic cruise ship. Her life was the basis for a character created in the 1930s by the name of “The Unsinkable Molly Brown.” The Hannibal native’s life is highlighted in the Molly Brown Birthplace & Museum.

Hannibal also hit the big screen in summer 2022. The movie, “Lovers Leap,” features a rock formation on the southern edge of town that overlooks the Mississippi River. The cliff is the locale for a legend that involves a Native American princess and a warrior from warring tribes who end their lives by leaping off the formation after being cornered by other tribe members. The film was made by Jeffrey Tipton, who moved to Hannibal several years ago. Tipton’s film is based on the Native American legend. He calls it “Romeo and Juliet meets Ozark.” It’s now available on Amazon Prime Video after debuting at Hannibal’s Bluff City Theater.

Hannibal was also the site of another film premiere. A 10-minute documentary called “Flyover” made its debut at a Hannibal theater in 2021. The film was made by Brian White, a native of Palmyra, Missouri, just 20 minutes northwest of Hannibal. The movie’s title refers to the term given to the states in the middle of the country that people who live on the West Coast and East Coast fly over. The documentary focuses on the day in the life of a rural Midwest town. The film has since been in 10 festivals and there are now plans to turn it into a feature-length movie that details a year in the life of a small rural town.

——————————————–

From Mark Twain’s hometown, we head due south on Highway 61 until we hit the town of Wentzville, a community of 50,000 on the outskirts of St. Louis.

German farmers and craftspeople helped settle this area before the town was founded in 1855. The tobacco industry was strong from 1850 to 1880 with eight tobacco factories operating in 1860.

Wentzville has been the most rapidly growing community in Missouri in recent years.

The Vietnam War veterans memorial in Wentzville, Missouri. Photo by St. Louis Public Radio.

Besides its proximity to St. Louis, the town also has a General Motors truck and van assembly plant that has been operating since 1983. In August 2022, GM announced it was investing $1.5 billion in the plant to build the company’s next-generation mid-size pickup trucks. The first of the “next generation” trucks rolled off the assembly line in January 2023.

From 2013 to 2018, Serco operated an Affordable Care Act application processing center in Wentzville. It was one of three facilities that Serco oversaw in the nation, employing 1,500 people at its peak. In 2014, the Wentzville facility garnered national attention when reports came out that employees were sleeping or playing games due to a lack of work. The center closed in 2018 after its $1.2 billion, five-year contract expired.

Wentzville is home to the nation’s first Vietnam War veterans’ memorial. The tribute began in 1967 as a tree of lights to raise money to send gifts to military personnel. In 1985, it evolved into a pillar of granite with an eagle perched on top. The memorial is a stop on the annual “Run for the Wall,” a motorcycle caravan that begins in May in Southern California and rolls cross country to the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. A mural honoring Vietnam War veterans on a wall near the memorial was dedicated in May 2022.

Wentzville was also the final stop for musician Chuck Berry. The creator of “Johnny B. Goode” and other classic songs was born in St. Louis, but lived in Wentzville in his later years. He purchased his home near here in 1957 and died in that house in 2017.

————————————–

We hop on Interstate 70 eastbound toward St. Louis.

Right before we get there, we take a short detour north on Highway 67 to a place called the Edward “Ted” and Pat Jones Confluence Point State Park.

This public recreation area, which opened in 2004, is where the mighty Missouri and Mississippi rivers come together.

The park is 1,118 acres of shoreline and bottom land that also serves as a flyway for migrating birds. There are plans to re-create a natural flood plain much like what the explorers William Clark and Meriwether Clark encountered when they began their expedition from this confluence in 1804.

We should take this moment to admire the Missouri River.

Where the Mississippi and Missouri rivers flow together. Photo from flickr.

It’s the longest river in the United States at 2,341 miles, slightly longer than the Mississippi.

The Missouri flows east and south through 7 states from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains in western Montana. The states are Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas and Missouri.

Its watershed includes 10 states and two Canadian provinces in which 10 million people live. It’s been called the “Center of Life” in the Great Plains.

Native American tribes lived along the river for centuries. It was first seen by Europeans in 1673. Lewis and Clark traveled nearly the river’s entire length looking for the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. They discovered no such passage exists.

The Missouri was one of the major transportation systems for the westward expansion of the 1800s. Fur trade was also important.

In the 1900s, the river was used for irrigation and hydroelectric power.

There are now six dams along the main stem of the river. Channelization for better navigation has actually shortened the river by about 200 miles. Industrialization has also harmed the river’s ecology.

The Missouri ends its long journey at this spot north of St. Louis where it converges in a beautiful merging with the Mississippi River.

Where Westward History Began

Our journey for today is nearing an end, too.

We exit the confluence park and head back down Highway 67 in a southerly direction until it meets up again with Interstate 70.

That freeway takes us to St. Louis.

Along the way, we pass the suburb of Ferguson.

The town was founded in 1855 by William Ferguson who deeded 10 acres of land to the Wabash Railroad. The settlement sprung up around the train depot that connected the community to St. Louis.

Until the 1960s, Ferguson was a “sundown town” that prohibited Blacks after dark.

In 1970, Ferguson was 99 percent white. That has changed dramatically in the past 50 years.

Today, Ferguson is now more than 70 percent Black and just 22 percent white. The racial composition of this 17,000-person community came to national attention in 2014 when Michael Brown Jr., an unarmed Black teenager, was shot to death by a white police officer on the streets of Ferguson.

The street in Ferguson, Missouri, where Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by a police officer in 2014. Photo by Time magazine.

The shooting happened after officer Darren Wilson stopped the 18-year-old Brown and a friend after hearing reports that Brown had stolen merchandise from a nearby store. Witnesses accounts vary as to what happened next, but there appears to be agreement that there was an altercation between Wilson and Brown at the driver’s door window while Wilson was still in his patrol vehicle. The officer fired two shots, one of them striking Brown in the thumb.

Brown ran away with Wilson in pursuit. When Brown stopped and turned back toward the officer, Wilson fired 10 more shots, fatally wounding the teenager.

Brown’s death sparked weeks of demonstrations and confrontations between police and protesters. One point of contention was that in a majority African-American town, only 4 of the city’s 53 commissioned police officers were Black.

The protests returned in late May 2020 after the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. Seven Ferguson police officers were injured during the demonstration outside a police station.

The shooting of Brown also strengthened the Black Lives Matter movement that had begun the year before in response to the acquittal of the man who shot to death Black teenager Treyvon Martin in Florida.

Wilson was never charged in the case, although the incident was investigated for five years until prosecutors announced in 2020 that Wilson would not be prosecuted.

Ferguson has seen some changes in the past six years. The police force is more diverse. The county elected its first Black prosecutor in 2018. A better job market has been promised.

————————————–

St. Louis is no stranger to racial strife itself.

The city just 15 minutes south of Ferguson along Interstate 70 is well known for its history of red-lined neighborhoods in which Blacks and other people of color were not allowed to buy homes.

St. Louis had its own high-profile officer-involved shooting in 2011 when Anthony Lamar Smith was shot and killed by a white police officer. That officer was acquitted in 2017.

Like many cities, St. Louis has been dealing with homelessness, especially along its Mississippi River waterfront. In March 2023, city workers cleared out an encampment along the river after complaints from nearby business owners and concerns over public health issues. About two dozen residents of the encampment were transferred to local housing facilities before the heavy machinery rolled in. Another homeless encampment near City Hall was cleared in October 2023.

However, this city of 270,000 in the center of the country also has a rich history that’s intertwined with the expansion of the United States.

It’s known as the Gateway to the West. It once hosted the Summer Olympics and the World’s Fair in the same year. St. Louis also has a culture of blues music, barbecue and Italian food, and even championship chess.

Several hundred years ago, the region was a center of Native American Mississippi culture.

The city was founded in 1764 by French fur traders who named it after King Louis IX. The United States eventually acquired the territory in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

The Eads Bridge in St. Louis, Missouri, spans the Mississippi River. Photo by Wikipedia.

St. Louis grew along with the steamboat industry, becoming a major port along the busy Mississippi River. Its port is the second largest inland port in the United States. It’s also the northernmost point on the Mississippi that is ice free.

The manufacturing sector grew after the Civil War. In 1874, the Eads Bridge was completed, becoming the first Midwest span over the Mississippi. By 1890, St. Louis was the 4th most populous city in the country. In 1904, it hosted both the Summer Olympics and the World’s Fair, an event attended by 20 million people.

The city’s economy today is based on trade, transportation, manufacturing, medicine and tourism. Anheuser-Busch has its headquarters here. So does Energizer Holdings, Express Scripts, Monsanto and Purina.

St. Louis is actually small in terms of acreage, so suburbanization has played a role in the city’s population. St. Louis peaked at 856,000 residents in 1950 before dropping by two-thirds to its current population.

It’s fallen to the second most populous city in Missouri, well behind Kansas City. About 44 percent of the population is Black and another 44 percent is white.

There are a number of spots for tourists to visit here.

The most prominent is the Gateway Arch. The 630-foot-high sculpture is as wide as it is tall. It’s the world’s tallest arch and the highest human-made monument in the United States.

The $15 million arch was completed in 1965. It commemorates the Louisiana Purchase as well as the first civic government west of the Mississippi and the westward expansion of the United States.

The sculpture is part of the Gateway Arch National Park, a 91-acre preserve on the site of the Old Courthouse. That complex was where the famous Dred Scott slavery case was heard. There is a Dred Scott exhibit within the park.

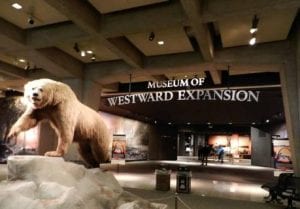

The Museum of Westward Expansion sits under the St. Louis Arch. Photo by TripHobo.

The Museum of Westward Expansion is underneath the arch. There’s also a memorial to President Thomas Jefferson, who negotiated and approved the Louisiana Purchase.

The city is also home to Forest Park, a 1,300-acre preserve that opened in 1876 and receives 13 million visitors in a typical year.

Another tourist attraction is the Chain of Rocks Bridge. The mile-long span was first opened to traffic in 1929. It connects Missouri and Illinois over a scenic section of the Mississippi River. It was part of Route 66 and famed for a 30 degree turn at its midpoint. The bridge closed in 1986 when Interstate 270 opened. It sat abandoned until 1999 when it was restored and reopened as a bicycle and pedestrian bridge. It’s one of the longest pedestrian/bicycle bridges in the world and has great views of the city as well as bald eagles hunting for fish in the river.

The World Chess Hall of Fame is also here. It opened in 2011 and features an autographed book by former champion Bobby Fischer as well as antique chess pieces.

Part of the reason the hall of fame is here is because of Saint Louis Chess Club. The group has hosted the U.S. Chess Championship every year since 2009. Its 6,000-square-foot complex contains tournament hall and classroom.

It’s a hangout for chess afficianados such as Susan Polgar, the former world champion who was inducted into the hall of fame in 2019.

Shannon Bailey, the chief curator at the Hall of Fame, said Polgar has helped bring a number of tournaments and championships to the city.

“She’s a rock star in the chess world,” Bailey told 60 Days USA in spring 2021.

Bailey explained that chess has a long history here. It started in 1886 when the world chess championships were held in New York, New Orleans and St. Louis.

It really grew when Rex Sinquefield and his wife, Jeanne, moved back to St. Louis after he retired from the finance industry in 2005. Sinquefield got involved in politics and other civic activities. One of them was the formation of the Saint Louis Chess Club.

“He had a deep connection to the game and he wanted to have a really nice chess club near his home,” Bailey said.

The World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of the World Chess Hall of Fame/Photo by Michael DiFilippo.

Sinquefield also helped bankroll the move of the Hall of Fame to St. Louis after the facility had closed in Miami, Florida, in 2008. The hall moved into a building that had been vacated next to the chess club facility.

Since then, both the hall and the chess club have taken off with continued support from Sinquefield, something members of the club and hall say they greatly appreciate.

Bailey said the club offers programs and lessons for everybody from beginners to more advanced players. They also provide free chess lessons for schoolchildren in St. Louis. In addition, they have instituted a chess merit badge program for the Scouts.

Emily Allred, a curator at the hall, said the free lessons have been offered to 75,000 students in 200 schools. In addition, 250,000 Scouts have earned chess badges.

Allred said chess helps children learn how to handle difficult problems as well as how to think creatively. In some schools, chess is now part of the curriculum.

Allred said chess is an ancient game with a lot of history that “anybody can play.” All you need is a board and the game pieces. You can even make those yourself.

“It’s accessible to anyone. It brings people together in such a beautiful way,” she told 60 Days USA in spring 2021.

Bailey adds that people don’t even need to speak the same language to play chess.

“It’s a great way to bring people together,” she said. “There seems to be a beautiful relationship between people who play the game.”

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 did not slow down enthusiasm at the Saint Louis Chess Club. That was mainly due to the Netflix series “The Queen’s Gambit” about a troubled and brilliant female chess champion.

Toasted raviolis are a specialty at Italian restaurants in St. Louis, Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

Bailey said people flocked to the hall and the club despite the limited operating conditions due to the pandemic. People said the Netflix show had inspired them to play chess. Sales doubled at the gift shop.

“We could not keep chess sets on our shelves,” she said. “It also gave us a chance to say, ‘See, I told you chess was cool.’”

“I was bowled over to see the interest it brought to the game,” added Allred. “I’m so happy to see more people gravitate to the game we love.”

Food is also a hot commodity in St. Louis.

The city is known for its Soulard District, a region full of barbeque residents and blues music. It also is bedecked with pizza parlors, live music venues, Southern restaurants and a farmers market established in 1779.

If Italian food is more your style, there are a number of restaurants that serve toasted raviolis, a dish invented in St. Louis. These eateries can especially be found in The Hill, an Italian neighborhood.

Between the food and the music, this seems like as good a place as any to stop.

More blues and barbeque ahead tomorrow as we cut across the center of Missouri on Interstate 70 with a college town and a presidential library along the way.