Day 59: Angling Across Oregon

May 17, 2021

Day 57: Pendletons and Ports in Eastern Oregon

May 15, 2021Most recently updated on February 28, 2024

Originally posted on May 16, 2021

Mount St. Helens. D.B. Cooper. The end of Cheryl Strayed’s “Wild” hike. And the city of Portland, a community whose name was decided by the toss of a coin.

There’s much to cover, so there’s no time to waste.

We head out of Boardman westbound on Interstate 84 on today’s journey. We immediately get a wide view of the mighty Columbia River, the largest river in the Pacific Northwest as well as the largest river flowing into the Pacific Ocean in North America. It’s also the fourth largest river by volume in North America.

The Columbia is 1,240 miles long with a 258,000-square-mile basin. The river starts in the Canadian Rockies in British Columbia. It travels northwest first before turning south into Washington. It eventually angles west and forms the border between Oregon and Washington as it winds its way to Portland and out into the Pacific. Along the way, the river irrigates 600,000 acres of farmland.

Several species of fish that migrate from fresh water to salt water, including salmon, live in the river. The Columbia used to produce more than 30 million salmon per year, most in the world, but now only a fraction of that number as well as smaller amounts of other fish swim in these waters due to all the dams on the river.

Native tribes lived along the Columbia for 10,000 years. The first European-Americans were Spanish explorers in 1775. Captain Robert Gray officially discovered the estuary of the Columbia River at the Pacific Ocean in 1792. Once he fixed the latitude and longitude of the river, scientists on the East Coast figured out the width of the North American continent.

In the 1800s, fur traders utilized the river extensively. Starting in the early 1900s, dams were built for power, irrigation and flood control. The river now has 19 hydroelectric dams, producing about half of the region’s electricity.

In December 2018, Oregon officials began a program to eradicate sea lions that were invading inland rivers, especially near Portland, in search of fish. In May 2019, a federal plan allowed for the killing of additional sea lions feeding on fish near the Bonneville Dam. In August 2020, a federal plan was unveiled that allows for the killing of more than 700 sea lions over a 5-year period ending in 2025. Wildlife officials say the sea lions in the Columbia River represent less than 1 percent of the population of these animals in the wild.

There’s also concerns about the number of abandoned ships that have sunk here. It’s estimated there are 129 of the vessels littering the river, many of them leaking pollutants into the waters. In September 2022, two of the sunken boats were removed by the U.S. Coast Guard. In June 2023, Oregon lawmakers approved $18 million to remove more abandoned vessels amid concerns over the asbestos and chemicals such as PCBs they might be leaking into the water.

In spring 2022, a new rule was instituted that requires drivers to obtain a permit to drive along the Historic Columbia River Parkway, the road commonly known as the “waterfall corridor” that includes many favorite tourist destinations.

————————————-

Interstate 84 follows the majestic Columbia as we continue westward along the northern border of Oregon.

We take this scenic route for nearly an hour and pass through the town of Biggs Junction, a community of less than 30 people along the river where I-84 meets up with Highway 97 out of the central Oregon town of Bend.

The community is named after W.H. Biggs, who settled in the area in 1880. The town was a stop on the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company rail lines. That route was eventually taken over by Union Pacific Railroad. The settlement was where travelers on the Oregon Trail would first see the Columbia River.

The main business in this small town is as a rest and refueling stop along the two main highways. This locale has the largest truck stops along I-84 in Oregon. Biggs Junction is also a wheat shipping point with grain storage elevators.

The Sam Hill Memorial Bridge, built in 1962, crosses the Columbia River here and connects Oregon and Washington.

However, we’re not ready to cross yet. There’s a special place just ahead where we can do that.

Trails, Volcanoes and Skyjackers

We skirt the Columbia River for another hour before we come upon what is known as the Bridge of the Gods.

This 1,858-foot-long span crosses the Columbia between Cascade Locks, Oregon (population 1,300) and North Bonneville, Washington (population 1,400).

The bridge had quite a history even before it became a focal point of a best-selling book.

The Bridge of the Gods at Cascade Locks, Oregon, is where Cheryl Strayed ended her “Wild” Pacific Crest Trail hike. Photo by AARoads.

There used to a be a natural earthen bridge at this spot, caused by a landslide about 1200 A.D. Native tribes used the dirt barrier to cross the Columbia River. This natural dam became legend with tribe members and appears to be the source of the name “Bridge of the Gods.” The barrier finally collapsed in the 1690s, perhaps due to earthquakes.

The current bridge opened in 1926 at a length of 1,127 feet. The span had to be elevated by 44 feet after the Bonneville Dam was completed in 1940. It’s also been lengthened to its current 1,858 feet.

In September 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew his Spirit of St. Louis plane under the bridge as he doubled back on a flight to and from Portland airport. People in Cascade Locks got to see Lindbergh zoom over the bridge, then do a “180” and “barnstorm” by flying under the bridge. The famed aviator had completed his successful solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean just four months earlier.

In more recent times, the Bridge of the Gods was made famous by Cheryl Strayed’s book “Wild.”

The bridge is where the Pacific Crest Trail crosses the Columbia River in the midst of its route from the Mexican border to the Canadian border. This spot’s altitude of 240 feet is the lowest elevation along the trail’s 2,660 miles.

Strayed finished her 1995 hike at the Bridge of the Gods. In her book, she describes how she felt when she reached the span after her long, soul-searching journey and how she sat down at a small café nearby on the Cascade Locks side and ate an ice cream cone.

My wife, Mary, and I both loved the book, so we had to check out the bridge during our 2017 road trip through the Pacific Northwest. We actually saw the skinny portion of the Pacific Crest Trail that Strayed would have walked down to reach the foot of the bridge. We also found what we think was the place where she ordered the ice cream.

As I mentioned in the Day One column, my friend, Mark Shuman, and I actually hiked the first mile and a half of Strayed’s quest in Mojave, California. So, I have seen the beginning and end of her route.

The toll for cars on the Bridge of the Gods was raised to $2 in 2016 due to the popularity of the 2014 movie “Wild” starring Reese Witherspoon. The toll was raised again in July 2022, reaching $3 for passenger vehicles where the drivers pay by cash or credit card (as opposed to a pre-purchased electronic toll).

Cascade Locks also holds a Pacific Crest Trail Days festival in late August that celebrates hiking, backpacking and camping.

——————————————–

The Bridge of the Gods is the perfect spot to cross the Columbia River and reach a milestone of our own. As we glide off the bridge’s northern terminus, we enter Washington, the 48th and final state on our 60-day virtual journey.

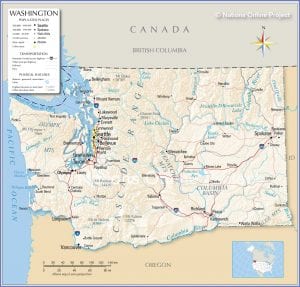

The Evergreen State is the 18th largest state in area at 71,298 square miles. It’s the smallest state in the continental United States west of the Rocky Mountains. It’s also the only state named after a president.

Washington is the 13th most populous state with nearly 8 million residents. It’s the second most populous west of the Rocky Mountains, trailing only California. Much of that is due to Seattle, the 18th most populous city in the country with 780,000 residents. About 60 percent of people in Washington live in the Seattle metropolitan area.

Native American tribes lived in the Washington area for thousands of years. Many were known for their colorful totem poles.

The first European arrival was a Spanish explorer who landed along the coast in 1775. British explorers arrived around 1790. In the early 1800s, fur trappers began to settle here. The territory was handed over by the British to the United States as part of the Treaty of Oregon in 1846.

The early economy involved logging, canning, mining and agriculture. Yakima Valley developed as one of the state’s many apple production regions. Wheat farms emerged in the eastern basin. Seattle eventually developed as a major trading port with Alaska and other areas.

The ship building industry grew during World War One and World War Two. Boeing made its headquarters in Puget Sound.

During the Great Depression, dams were built along the Columbia River to produce electricity. The final one was the Grand Coulee Dam, which was finished in 1941. It’s still the largest concrete structure in the United States and one of the world’s leading hydroelectric producers.

Washington’s economy today is diverse.

In agriculture, Washington is the top producer of apples with more than half of the nation’s crop. It’s also one of the top states for pears as well as tops in hops and sweet cherries. Washington is also a leading producer of lumber due to its forests of pine and fir. It’s the second leading producer of wine (behind California) as well as potatoes (behind Idaho).

Commercial fishing is another strong sector of the economy. The manufacturing industry includes ship building, missiles and aircraft as well as transportation machinery. Washington also has more than 1,100 dams for electricity, flood control, irrigation and water storage. It generates more hydroelectric power than any other state.

Boeing is headquartered in the Seattle area. Its Everett facility is the world’s largest building by volume with 98 acres and 472 million cubic feet of space. Disneyland could actually fit inside the building with room left over for parking.

Microsoft and Amazon have headquarters in Washington as does Nordstrom, Costco, Starbucks and Alaska Airlines. One reason is the state has no corporate or personal income tax.

Washington is a progressive state. It was among the first to legalize same-sex marriage (2012) as well as recreational and medicinal marijuana. The state also legalized physician-assisted suicide with a Death With Dignity Act in 2009.

The minimum wage here is $16.28 an hour, among the highest in the nation. In May 2019, the state approved the first public option health plan for its residents. The Cascade Care plan took effect on January 1, 2021.

————————————-

You can’t drive into southern Washington without at least making an attempt to get a close-up glimpse of Mount St. Helens.

So, from the Bridge of the Gods we backtrack a bit east on Highway 14 and then head north on the Wind River Highway, which eventually downgrades to Wind River Road. After an hour and a half on these windy, two-lane roads we get pretty close to the famous volcano when we reach the northwest corner of Swift Reservoir.

The view of Mount St. Helens in Oregon from a visitors’ center. Photo by Seattle Met.

Mount St. Helens is the most active volcano in the Cascade Range. The mountain began to form about 40,000 years ago after the last Ice Age. The volcano experienced at least nine major eruptions by the mid-1800s but had been dormant since 1857.

That all changed on May 18, 1980 when Mount St. Helens blew its stack with a powerful eruption. It was one of the most violent volcanic explosions ever recorded in North America. The eruption launched rock and ash 12 miles into the air, decimated 230 square miles of forest and killed 57 people. Over the next two weeks, Mount St. Helens sent 520 million tons of ash eastward over 22,000 miles.

From 1980 to 1986, there were 17 additional eruptions, forming a new lava dome 820 feet high and 3,600 feet in diameter. Earthquakes and smaller eruptions have occurred since, indicating the volcano is still active.

The 110,000-acre Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument was established in 1982. It preserves the site for scientific study and serves as an education tool for visitors. The U.S. Forest Service planted 10 million trees after the eruption. Otherwise, the environment has been left alone to recover naturally.

The park has two main visitor centers. One is the Silver Lake center just east of Castle Rock and the other is the Johnston Ridge Observatory in the heart of the monument and only five miles from the volcano’s crater.

Both are too far away to visit today, so we turn out attention west and south.

——————————-

Just a few minutes from Swift Reservoir on westbound 503 lies the town of Cougar, a community of about 120 people that is the closest occupied area to Mount St. Helens. The village along Yale Lake sits at an elevation of 502 feet and is about 11 miles from the bulk of the volcano.

The town was named after the cougars that live nearby. A post office was established here in 1902.

The Ape Cave lava tubes near Cougar, Washington. Photo by TripHobo.

Cougar was never a big town, but enough people left after the 1980 eruption that it was disincorporated before the 2000 census.

The motto on village logo says it all. It reads: “Mount St. Helens Changed Our World.”

Still, the area is marketed as a great fishing spot as well as good place for hiking and skiing. Ape Cave is about 10 miles away. The cave is a lava tube 13,042 feet in length, the third longest lava tube in North America. It has a year-round temperature of 42 degrees. The tube was formed 1,900 years ago by a Mount St. Helens eruption. It was first discovered in 1947 and first explored in the early 1950s by a Scout troop. The name comes from a 1924 attack on five miners in a small cabin in Ape Canyon by “ape men.” The area was the locale of a 2002 Bigfoot sighting.

There are a few businesses in the Cougar area. One is the Cougar Store, a gas station with some food items. There’s also the Cougar Bar and Grill, whose menu lists items such as a volcano burger, an Ape Cave sandwich and a Bigfoot house special.

——————————–

If that isn’t strange enough for you, we head west on Highway 503 for another half-hour until we reach the community of Ariel.

The town of 1,300 people along the Lewis River mostly consists of scattered houses and ranches. The region gets 87 inches of precipitation in an average year, one of the highest amounts in the United States.

The Cowlitz and Chinook tribes lived in this area for centuries, utilizing the Columbia and other rivers. European settlers first arrived in the region in the 1820s. Fur trapping was a big industry.

What has put Ariel on our map is its connection to perhaps the most famous plane hijacking in the 20th century.

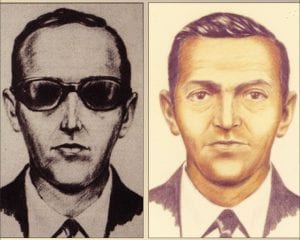

That skyjacking happened on Wednesday, November 24, 1971, right before Thanksgiving weekend. A quiet man in his 40s who used the name Dan Cooper paid cash for a $20 one-way ticket on Northwest Orient Airlines flight 305 from Portland to Seattle.

Sketches of the 1971 skyjacking suspect known as D. B. Cooper. Photo by Maxim.

Shortly after takeoff at about 3 p.m. the man handed a note to a flight attendant saying he had a bomb in his briefcase. He demanded four parachutes and $200,000. The plane landed in Seattle. All 36 passengers were removed. A bundle of cash and four parachutes were given to the flight crew and taken to the skyjacker.

The plane was re-fueled and took off again with only the skyjacker and the crew on board. This time the plane was headed for Mexico at the demand of the skyjacker. About 8 p.m., 10,000 feet over the Mount St. Helens region, the aft door was opened and the passenger disappeared as did two parachutes.

The name of the skyjacker was reported as D.B. Cooper after a reporter misheard the information and reported the hijacker as “D.B.” instead of Dan. Despite all the publicity, the mysterious hijacker seemed to have disappeared from the face of the Earth.

Now, this is where the town of Ariel comes in.

Initial estimates had concluded that Cooper would have landed somewhere near Ariel if he did indeed survive his parachute leap.

No one in town ever reported seeing anyone matching Cooper’s description, but the community did have some fun with the mystery.

Every November on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, the town used to hold a D. B. Cooper Days at the Ariel Store and Tavern to commemorate the 1971 skyjacking involving the mysterious D. B. Cooper, a guy some locals felt “beat the system.”

The annual celebration started in 1974 and then took off when Dona Elliott, who bought the store in the late 1980s, decorated the shop with Cooper memorabilia and made the event famous. Hundreds of people attended some years.

Dona’s Ariel Store Pub in southern Washington used to hold an annual D. B. Cooper Days festival. Photo by The Mountain News.

The event was cancelled in 2015 after Elliott died. Dona’s Ariel Store Pub hasn’t reopened since.

The mystery of D.B. Cooper lives on to this day.

In 1980, about $5,800 of the ransom money was discovered by a boy along the Columbia River about 20 miles southwest of Ariel. In August 2021, a self-described D. B. Cooper expert began digging along the banks of that portion of the river, hoping to find clues to the mysterious hijacker.

The skyjacking led to the Cooper Vane being installed on Boeing planes. The aerodynamic device prevents the back stairs from being deployed while an aircraft is in midair. That makes it tough for anyone such as a D. B. Cooper to jump out of the back half of a plane while it’s in flight.

After the hijacking, the FBI interviewed 800 people and considered two dozen potentially credible suspects. They arrested a man five months after the incident, but he was ruled out because he didn’t match Cooper’s physical description.

Investigators kept the investigation, dubbed by authorities as the NORJAK case, open until July 2016, when they officially closed it.

In January 2021, Rolling Stone published an interview with former flight attendant Tina Mucklow, the person who had the most contact with Cooper during the flight.

In 2022, Netflix debuted a 4-part series called “D. B. Cooper: Where Are You?” that detailed not only the case but also the amateur sleuths who have tried to solve the mystery.

In January 2024, a man said his mother told him that his father, Rick McCoy Jr., a Vietnam War veteran and an experienced parachutist, was the skyjacker known as D. B. Cooper. McCoy was arrested during an attempted skyjacking in 1972. He was sentenced to 45 years in prison, escaped and then died in a shootout with police in 1974.

There have been a number of other claims made as to who D.B. Cooper was, but none have been substantiated. Some of them involved people who seemed to have suddenly and quietly come into a whole bunch of money.

Many experts believe the hijacker did not survive the parachute jump and his body long ago decomposed in the remoteness of the Mount St. Helens region.

There is one puzzling fact to that theory, though. If D. B. Cooper didn’t survive, why wasn’t there ever a report from somebody about a brother or cousin or friend or coworker who suddenly disappeared in November 1971?

A mystery to which we may never have an answer.

————————————-

One last stop in Washington and it’s right at the border.

Vancouver is about 40 minutes southwest of Ariel along the Interstate 5 corridor where the freeway crosses the Columbia River into Oregon.

The city of 198,000 is the fourth most populous in Washington. It’s also one where vaccinations were a flash point a few years ago.

Native American tribes, including the Chinook, lived in the area for hundreds of years. The first European contact was in 1792. The explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark passed through in 1805 and on their way home in 1806. By then, much of the Chinook tribe had died from diseases such as small pox that were introduced by white visitors. By 1830, there were only a couple dozen survivors from what was once 80,000 tribal residents.

Fort Vancouver was established in 1825 by the Hudson Bay Fur Company as a trading post where staples such as coffee, tea and sugar were swapped for furs and pelts brought in by trappers. The town was named after Captain George Vancouver (as was Vancouver, British Columbia). The captain had mapped the Northwest coast in 1792. Part of the reason for the fort was to try to establish British control of this region. The Fort Vancouver National Historic Site was established in 1948 in recognition of the protective facility.

The Fort Vancouver National Historic Site in southern Washington. Photo by Scenic Washington State.

The U.S. Army arrived in the region in 1849 and built officers’ housing, a neighborhood that eventually became known as Officers’ Row that was a temporary home to Ulysses Grant, among other soldiers

The Army’s presence encouraged more settlers to come. Vancouver incorporated as a city in 1857. Farmers grew crops in the outlying areas and by 1867 Vancouver had seven merchandise stores. Wood product manufacturers emerged as did brick manufacturers. In the 1890s, the city was listed as having five saw mills, two sash and door manufacturers, three brick yards, a box manufacturer and a brewery.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, prunes were dried and canned in the city. From 1900 to 1910, Clark County shipped 16,000 tons per year. In the 1920s, the county was known as the prune capital of the world.

The North Bank Railroad arrived in 1908. A toll bridge across the Columbia River was finished in 1917.

Prohibition began in Vancouver in 1915, four years before the national ban. The restrictions and bad weather were part of the reasons the prune industry eventually dried up.

During World War One there were two shipyards, one for wooden ships and one for steel ships. In November 1918, the flu pandemic shut down Vancouver. Celebrations for the end of the war were even cancelled.

The Ku Klux Klan was active in Vancouver in the 1920s. A 1924 rally attracted 500 KKK members

The Alcoa plant opened in 1940, two years after the Bonneville Dam was built. It produced the first aluminum west of the Mississippi River.

Henry Kaiser opened a shipyard in 1944 that employed 36,000 people and built 140 ships and two dry docks during World War Two. The Vancouver Housing Authority built six developments to handle the influx of workers. The housing discrimination that civil rights activists noted there prompted the formation in 1943 of a local chapter of the NAACP.

Interstate 5 arrived in 1955. However, there was no downtown exit, so the city’s core faded. In 1994, city leaders approved a plan to revitalize the downtown area. It was rewritten in 2004 and updates were completed in 2011 and 2016. In February 2021, The Columbian newspaper reported that the downtown area was undergoing a construction boom with seven major projects under way or recently completed. Most of the new square footage will be residential units with some office space and hotel rooms.

The local economy today is more high-tech and service oriented. Since 2000, more than 300 high-tech companies have set up shop. Nautilus Inc. is also headquartered here.

Vancouver residents shop in Portland because there’s no sales tax in Oregon, but they live and work in Vancouver because there’s no income tax in Washington. Vancouver residents who work in Oregon have to pay Oregon income tax. In 2019, a new law got rid of the practice of Oregon residents not paying sales tax when they buy products in Washington.

Vancouver was an anti-vaccination “hot spot” that caused a measles outbreak in January 2019. In July 2019, Washington legislators enacted a law eliminating personal and philosophical exemptions for these type of vaccinations.

Pulling Into Portland

For today’s final destination, all we have to do is cross the Interstate 5 bridge over the Columbia River as we leave Washington and re-enter Oregon, the sixth state we’ve visited more than once.

Upon crossing, we immediately land in Portland, a city with little religion as well as a lot of roses, strip clubs and breweries as well as the world’s smallest park. It’s also the town whose name was decided by the flip of a penny.

There are nearly 620,000 residents in Portland, making it by far the most populous city in Oregon. In fact, more than half of the state’s population lives in the Portland metropolitan area. The city is also the second most populous in the Pacific Northwest, behind only Seattle.

The penny that determined the name of Portland, Oregon. Photo by Bellevue Rare Coins.

Portland gets 36 inches of rain a year. It’s called the “The City of Roses” and is known for its eco-friendly bike paths and 10,000 acres of city parks. It’s also home to both the University of Portland and Portland State University.

The first settlement was established in 1843 when two men beached their canoes on the banks of the Willamette River and filed a land claim. Other settlers arrived via the Oregon Trail.

In 1845, Francis Pettygrew of Portland, Maine, and Asa Lovejoy of Boston owned much of the town’s land. They each wanted to name the city after their hometown. They decided the debate with a coin toss. Pettygrew won two out of three and named the town Portland. The “Portland Penny,” the coin that was used, is on display at the Oregon Historical Society headquarters.

In 1851, the city was incorporated with 800 residents. At that point, the town had a steam sawmill and a log cabin hotel. The main ingredients of the economy included fishing, lumber, wheat and cattle. Portland grew because of its rivers and railroads. The Northern Pacific Railroad arrived in 1883. Three bridges were built over the Willamette from 1887 to 1891.

From 1850 to 1941, the city was known as a dangerous port town with organized crime elements.

Nonetheless, by 1900 there was 90,000 residents. By the 1930s, that had risen to 300,000 residents. During World War Two, the Portland Assembly Center processed Japanese American residents, housing some and sending others to internment camps elsewhere. The center had a peak population of 3,676.

Over the decades, various sectors of the city have served as Japantown and Chinatown communities.

In the 1960s, hippies and other counter-culture folks moved in and the city became more progressive with food co-ops and a vibrant music scene. The Crystal Ballroom was popular with bands such as Buffalo Springfield and The Grateful Dead performing. City residents also took on causes such as Native American rights, gay rights and the environmental movement. In the early 2000s, a large LGBTQ community was established.

Free speech is also a big issue here. In 2008, a judge dismissed charges against a nude bicyclist, citing First Amendment rights. There is also a nude bicyclist event every year. That free speech has slipped over into the adult entertainment world. Portland has more strip clubs per capita than any other U.S. city, including Miami and even Las Vegas.

The liberal political bent here has apparently taken a toll on local residents.

Damage from protesters have dissuaded residents from visiting downtown Portland. Photo by KOIN.

A poll released in May 2021 revealed that people who live in Portland planned to visit the downtown area less often due to homelessness and the Defund the Police protests that had been held the previous year. In the survey commissioned by The Oregonian newspaper, those questioned used words such as “dirty,” “riots” and “unsafe” to describe the city’s core. The newspaper reported that the downtown area was rife with homeless tents, smashed windows, graffiti and boarded-up business, despite the fact that the anti-police demonstrations that raked the city had mostly faded.

A survey published in August 2021 indicated that a vast majority of restaurant and bar owners downtown believe the COVID-19 pandemic as well as homelessness and vandalism have significantly affected their business. About 20 percent said they planned to relocate to another part of the city. In August 2022, researchers reported that Portland was experiencing one of the slowest post-pandemic recoveries of any major U.S. city. In November 2022, the owner of the Rains PDX closed her downtown store, leaving a note on the front doors citing the number of break-ins as the reason. A February 2023 report stated that downtown Portland is still struggling to rebound economically. An October 2023 report stated that foot traffic in downtown Portland was only 61 percent of what it was in 2019.

The homeless crisis appears to be spreading across the city. In October 2022, it was estimated there were more than 3,000 homeless people living in 700 encampments in Portland. The mayor said he planned to ban homeless encampments on Portland streets and establish at least three large, designated campsites near city services for the homeless. In January 2023, Oregon’s governor signed legislation declaring a state of emergency over homelessness and laying out plans to build 36,000 new housing units statewide. In May 2023, officials reported a drop in chronic homelessness in the Portland area, but housing advocates said few homeless people have found permanent housing. In October 2023, plans were announced for the second of six major encampments for homeless people.

The city is also grappling with a high number of killings. In 2021, 90 people died by homicide in Portland, surpassing the record of 66 set in 1987. Gang violence as well as shortages in police staffing and budgets were blamed. In May 2022, the police chief announced a shift in resources within the department to move more personnel to the homicide unit. Despite those measures, there were 101 homicides recorded in Portland in 2022, another new record. That number dropped significantly to 74 homicides in 2023.

Nonetheless, technology companies have been moving into Portland since before World War Two. One of the first was the U.S. Forest Service Radio Lab established in the 1930s. In the 1950s, Tektronix set up camp in the Portland area. In 1963, the Oregon Graduate Center was formed to create a hub for education, research and development. In 1976, Intel set up a facility in the region. By 2006, more than 1,500 tech firms were located in the Portland area, earning the region the nickname of Silicon Forest. In recent years, some companies have been migrating to Portland from the San Francisco Bay Area.

The city’s economy is driven by low energy costs, accessible resources, freeways, airport, railroad and docks.

The Port of Portland is also a major player. The port handles 13 million tons of cargo per year. Portland is the largest shipper of wheat in the United States. It’s also the largest potash exporter in the world as well as the largest facility on West Coast for imports of automobiles.

The steel industry was the biggest employer in town in the 1950s. The city is still home to Schnitzer Steel and EVRAZ.

There is also a cluster of athletic shoe manufacturing companies. Nike has its world headquarters in nearby Beaverton.

Food carts are popular in Portland, Oregon. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

Portland is home to nearly 70 breweries, one of the highest totals of any city in the world. In addition, there are “brew and view” theaters that show second-run, art and revival films.

The city is also known for its “street food” from food trucks and food carts. More than 500 of them at last count. The carts actually endured the COVID-19 pandemic in reasonably good shape because they filled a need when restaurants closed.

Portland also sports a multitude of coffee roasters.

The International Rose Test Garden in Portland, Oregon. Photo by AFAR.

The variety and quirkiness of the city was captured in the television series “Portlandia.” The show was filmed on location in Portland and ran for eight seasons from 2011 to 2018. The show made light of Portland’s liberal politics, organic food and alternative lifestyles.

There are a number of sites for tourists to take in when they come to Portland.

One is the Oaks Amusement Park, which opened in 1905 and was once known as “Coney Island of the Northwest.” Besides rides, there is also a roller skating rink and a miniature golf course here.

One of the city’s pride and joys is the International Rose Test Garden. It was approved in 1917 and dedicated in 1924. It’s the oldest public rose test garden in the country. The 5-acre facility is in Washington Park. The garden has more than 10,000 roses.

If reading is your thing, you can stop by Powell’s City of Books, the world’s largest independent book store. The shop, established in 1971 in a former car dealership, takes up an entire city block. The 3-story complex has 9 rooms and more than 1 million books.

Finally, Portland has the world’s smallest park. The Mill Ends Park, all 452 square inches of it, is in a median on SW Naito Parkway. The park was started by newspaper columnist in 1948 who used to look out his window at a hole in the street where a light pole was never installed. When weeds grew, he decided to make the 2-foot-wide circle into a tiny park, joking it was for leprechauns.

We can put our vehicle into park for the day.

Tomorrow, we’ll see a lot more of Oregon, including the center of the state as well as some of its fabled coastline.

Along the way, we’ll check out a driftwood museum, one of the best spots to “storm watch” and the only place in the continental United States that was bombed by the Japanese during World War Two.