Day 2: A Grand Tour of Northern Arizona

March 21, 2021

The Basics of This Adventure

December 16, 2020Most recently updated on March 1, 2024

Driven on March 18-19, 2022

Originally posted on March 20, 2021

If you read the weather pages, then you’re probably familiar with Needles, California.

On any given day in any season, Needles can be listed as the hottest spot in the United States, even outshining the Death Valley region four hours to its northwest.

That shouldn’t be surprising given the climate here.

On average, Needles has 281 sunny days a year with only 22 days of precipitation that produce an annual rainfall of 6 inches.

Temperatures above 110 degrees are not unusual during the summer and 120 degrees is not out of the question.

The town of 4,800 residents also holds some unusual weather-related records.

There are reports that on July 22, 2006, the temperature in Needles never dropped below 100 degrees, one of the few times a place in the United States has had its thermometer stay at triple digits for 24 hours.

On August 13, 2012, there was rain falling that was measured at 115 degrees before it turned to steam and evaporated in mid-air. That is thought to be a world record.

On May 4, 2014, Needles recorded a temperature of 102 degrees with a dew point of minus 38 degrees for a relative humidity of 0.33 percent, a measurement that tied an afternoon in Iran for the lowest value ever recorded on Earth.

Weather aside, Needles also has its cultural lore.

In the comic strip “Peanuts,” Snoopy’s brother Spike lived in the desert near Needles, owing to the fact that Charles Schultz, the creator of the comic strip, lived here for two years as a boy.

The town is also mentioned in the song “Never Been to Spain” when the singers of Three Dog Night harmonize “Well, I headed for Las Vegas. Only made it out to Needles.”

Needles is as far east as you can get in California. It sits along the Colorado River at the Arizona border.

It was built on the strength of the railroads and is connected to the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s.

It has tried to reinvent its economy a number of times and is now seeing some success with its new cannabis industry.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Needles is the end of our Day 1 journey.

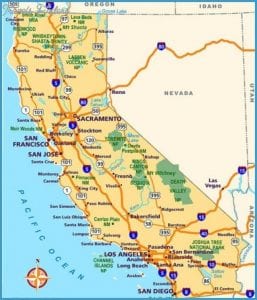

Let’s go back to the beginning of today’s route and kick off this trip that cuts diagonally across California.

Heading Out

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll mark our starting point as San Francisco and head east over the Bay Bridge, past Oakland and Berkeley, and into the suburban reaches of the Bay Area.

Less than an hour after departing, we zoom through the city of Livermore heading east on Interstate 580.

The town is home to Lawrence Livermore Lab, a complex whose primary mission is the development of nuclear weapons. It’s one of three national laboratories overseen by the U.S. Energy Department National Nuclear Security Administration. In recent years, the lab has been broadening its horizons. In December 2021, it established an incubator program for developing artificial intelligence projects. In December 2022, the lab made national news when scientists announced they had made a historic breakthrough by achieving fusion ignition, potentially setting the stage for major advancements in the creation of clean energy.

Livermore is also home to the Centennial Light Bulb, the world’s longest lasting light bulb. It’s been burning inside Livermore Fire Station #6 since 1901. The only time it hasn’t been illuminated is during power outages and for 22 minutes in 1976 when the fire station was moved to a new location. Although its original 30 watts of power has been dimmed to 4 watts, it has still shone for more than 1 million hours. The bulb even has a website where you can watch it shine in real time.

This area is also part of rock ‘n’ roll lore due to a Rolling Stones concert in December 1969. The legendary group was putting on a free concert at the old Altamont Speedway in the hills north of Livermore when one of the Hells Angels bodyguards hired by the Stones for security stabbed to death an 18-year-old man who was toting a gun. The incident was spotlighted in the documentary “Gimme Shelter” about the Stones’ 1969 tour.

It’s not an event remembered by many in this suburb of 81,000 people.

As we slide past Livermore’s eastern city limits, we start to leave behind the San Francisco Bay Area, which at more than 3.2 million residents (without the San Jose region) is the 13th most populous metropolitan area in the United States.

Just outside of Livermore, large windmills start to populate the rolling hills on both sides of the freeway.

The churning, power-generating blades are part of the 58-square-mile Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area that was established by a three-county consortium in 1980 in response to the 1970s energy crisis.

Some of the wind energy turbines in the Altamont Hills near Livermore, California

At one point, there were 6,000 turbines producing 330 megawatts of electricity on this land owned by cattle ranchers. Even though this was defined as clean energy, there was still an environmental problem. Between 2,000 and 4,000 birds per year were being killed after flying into the turbine’s sharp metal blades that can spin at more than 150 miles per hour. Among the feathered fatalities were dozens of golden eagles.

Starting in 2011, many of the old turbines have been replaced with more efficient machines that contain smaller blades. The new structures also don’t have the lattice stands that birds loved to perch on. Each new turbine replaces 23 older ones. As of September 2021, 569 of the older turbines had been replaced by 23 strategically placed start-of-the-art machines, making the hillsides much less populated by the spinning blades. It’s estimated the newer blades can provide clean energy to the equivalent of 47,000 homes.

The Altamont energy program is now the oldest operating wind farm in the United States. It’s also one of the largest concentrations of wind turbines in the world. As of December 2022, it still had more than 5,000 wind turbines capable of producing 580 megawatts of electricity.

The Land of the Super Commuters

As we glide down out of the Altamont hills, the western fringes of California’s flat and fertile Central Valley come into view.

We quickly encounter the sprawling communities of Tracy and Mountain House.

These bedroom communities are growing for one primary reason. The median price for a home in the Bay Area is $1.1 million. That’s nearly triple the national average of $420,000.

The median home price in Mountain House is about $830,000. The median in Tracy is about $760,000.

Mountain House is a new town, carved from the flatlands east of the Altamont Hills. It’s a carefully planned community with a rectangular grid of large homes along tree-lined streets with light industry centers sprinkled on the edges. There are two elementary schools and a large high school with expansive sports fields. A new shopping center with the town’s first supermarket, a Safeway, opened in 2022. A report in the San Francisco Chronicle in October 2023 detailed where this town of 30,000 has succeeded and where it has fallen short. One of the biggest issues is the lack of local jobs. There are only about 1,500 of them in Mountain House, forcing residents here to drive elsewhere for work.

Indeed, there is a price to pay for living out here. You have to drive a distance for the good-paying jobs in Silicon Valley and other parts of the Bay Area. The average one-way commute of a Mountain House resident is 1 hour. For Tracy residents it is 44 minutes, well above the national average of 27 minutes.

This long slog doesn’t seem to be dampening the enthusiasm of people searching for cheaper housing in what is known as the “exurbs.” Tracy has grown from 18,000 people in 1980 to 101,000 today. More are coming, too. The Tracy Hills subdivision is adding nearly 6,000 new homes to the southwest part of town. From the freeway south of town, you can see the first wave of the subdivision’s similar-looking, 2 -story homes lined up row after row over acres and acres.

Some of the homes in the Tracy Hills subdivision on the edge of California’s Central Valley

In this northern sector of San Joaquin County, there were an estimated 80,000 commuters who traveled to the Bay Area before the COVID-19 pandemic. The average round trip is 120 miles. Some “super commuters” travel 2 hours each way to their job so they can afford a home they can enjoy on the weekend.

This trend is transforming some of the towns in this slice of the Central Valley.

One of those communities is Manteca, about 15 miles east of Tracy.

The town was founded in 1861. It was supposed to be called Monteca, the Spanish word for cream. However, railroad officials misprinted the name as Manteca, the Spanish word for lard. It’s a long-running joke in town.

Manteca was primarily an agricultural community until it slowly started to change in the 1970s. The 1996 closure of the Spreckels Sugar factory after 75 years of operation hastened that metamorphosis.

Since then, the town of nearly 90,000 residents has tried to lure high-tech businesses and establish itself as more of a “bedroom community” to the eastern fringes of the Bay Area.

You can see the evidence along the highway with hundreds of newer homes stacked neatly along straight streets with views of the Altamont Hills in the far distance.

A Taste of the Central Valley

As we turn south out of Manteca, we zip onto Highway 99.

This roadway has been around for almost 100 years.

Construction began shortly after California’s first highway bond measure was approved in 1910. Portions of the thoroughfare became Highway 99 in 1926. It was one of the original U.S. highways.

The road was an important route in the 1930s as passenger cars as well as commercial trucks zoomed between Los Angeles and the northern reaches of the state. Towns dominated by the agricultural industry grew up along the route. The road became known as the “Main Street of California.”

That changed in 1956 when construction began on Interstate 5 along a parallel path to the west. That freeway bypassed all the major Central Valley towns and provided motorists with a quicker route up California’s spine.

Since then, parts of Highway 99 have been truncated or melded with other roadways. The highway now runs just 424 miles from the Bakersfield area to Red Bluff, a town 130 miles north of Sacramento.

Nonetheless, Highway 99 remains a workhorse. On its busiest stretches, more than 10,000 vehicles can pass per hour.

That has also made the mostly four-lane highway unsafe. A 2018 study ranked it as the country’s most dangerous road with 62 fatal accidents per 100 miles per year.

Travelers and in particular truckers seem to feel the roadway is worth the risk. All the major Central Valley towns still lie along the route and depend on it.

One of those communities is Modesto.

It’s just 20 miles south of Manteca, but the agriculture-based community is much more Central Valley than it is Bay Area exurb.

About 216,000 people live here with 42 percent of the population listed as Hispanic or Latino. The median price for a home is about $430,000.

This town was founded in 1870 along the shores of the Tuolumne River, which provided settlers with a continuous source of water. The big landowner was a man named William Ralston. Officials wanted to call the settlement “Ralston,” but the land owner was too humble and declined. So, the founders named it Modesto, the Spanish word for “modest,” in Ralston’s honor.

The agriculture industry began when farmers started planting wheat due to a worldwide shortage of that grain. The Central Pacific Railroad tracks arrived in 1870, allowing Modesto crops to be transported across the region. In 1903, the introduction of irrigation further expanded the town’s farm economy.

The George Lucas Plaza in Modesto, California, honors the movie director who grew up here.

The area’s rich farmland has allowed agriculture to remain the chief industry to this day. Almonds are the biggest commodity while walnuts, peaches, milk, chickens and cattle are also plentiful. In addition, the town is a big farm-to-table community.

Grapes also grow well here as Ernest and Julio Gallo found out. They started a winery in town in 1933 after Prohibition ended. The brothers read about winemaking from pamphlets in the Modesto Library basement and began their operation with a $6,000 investment. The E&J Gallo Winery has had a long history of labor strife with farmworkers that has included boycotts of Gallo products. However, the winery remains in Modesto and is now the largest privately owned winery in the world. The family name also adorns the Gallo Center for the Arts downtown.

Perhaps Modesto’s most famous native son is movie director George Lucas. The creator of the “Star Wars” franchise grew up here, graduating from Thomas Downey High School in 1962. His first hit film, “American Graffiti,” in 1973 was based on his teen years cruising up and down 10th and 11th streets. There’s a George Lucas Plaza in a small triangular island where 10th, 11th and three other streets meet. It has a sculpture of a teenage boy and girl sitting on the hood of a car. A plaque dedicated to Lucas is also there.

Not too far away was a homage to those “Graffiti” years. The city’s last drive-up restaurant, an A&W Root Beer, sat in a mostly residential neighborhood near 14th and G streets. The restaurant, which opened in 1957, had a lot of historical items from those cruising days and was part of the city’s month-long Graffiti Summer celebration that begins in June and lasts until the first days of fall. In addition, an Elvis Presley impersonator entertained crowds every Friday night from June to October as people rolled up in their antique cars. This A&W was well-known for its waitresses who roller skate to cars in the parking lot to deliver orders.

However, the restaurant’s days appear to be over. In November 2023, the owner closed the restaurant after a lawsuit was filed over the lack of access for disabled people. The owner had put his business up for sale a few months before but decided to shut its doors after the legal action was taken. It seems unlikely the hamburger stand will reopen.

If you roll out of town along 9th Street you snatch a glimpse the historic arch that adorns that avenue. The sign says “Modesto: Water, Wealth, Contentment and Health.” The slogan was selected during a 1911 contest. The winner got $3 for coming up that motto. The arch was finished in 1912 and has been hanging over 9th Street ever since.

————————————–

Back on Highway 99, the Central Valley really opens up.

This midsection of California is 450 miles long and ranges from 30 to 60 miles wide. Its 18,000 square miles make up 11 percent of California’s total land area.

This region of the valley does have a geographic claim to fame.

Along Highway 99 in the town of Madera, there is a pine tree that sits adjacent to a palm tree in the freeway median. It doesn’t seem like much as you drive by, but Madera officials say these two trees represent the dividing line between Northern California and Southern California. The palm represents the southern half of the state while the pine is symbolic of the northern half.

The Central Valley isn’t necessarily scenic. Acres and acres of crops spread out over miles and miles of flat land formed by glaciers more than 10,000 years ago.

But its importance is indisputable.

The valley is considered one of the most agriculturally productive areas in the United States, perhaps the world.

The farms here produce crops worth $17 billion per year. About 25 percent of the food in the United States and about 40 percent of the nation’s fruits, nuts and other table foods are grown here.

The Central Valley is known for its row crops, in particular vegetables, tomatoes, lettuce, wheat and other staples. However, this region is also covered with fruit trees that burst with peaches, apricots and lemons. There are also 6,000 almond growers who produce 2.5 billion pounds of almonds every year. That’s 100 percent of the U.S. commercial domestic supply and 70 percent of the world’s production.

This volume of agricultural products would not be possible without the California Aqueduct, the 444-mile delivery system that transports water from Northern California into Southern California and the Central Valley.

The aqueduct as well as the volatile battle over water rights and what water shortages are doing to the valley are discussed in more detail in one of our Spotlight articles.

Water is the number one issue in the Central Valley, but it’s not the only one.

In recent years, the valley as well as other agricultural areas have faced labor shortages as current workers get older, fewer immigrants come into the United States and younger immigrants eye less physically exhausting work.

One solution has been to employ technology and use automated harvesting machines to pick lettuce as well as other crops. The robots can also be used inside packaging facilities.

The Central Valley is one of the fastest growing areas in California and that is creating issues for the 6.5 million people who live here.

Among the problems is air pollution from the increase in truck traffic as well as agricultural emissions. In 2019, the American Lung Association listed some the larger cities in the valley as having the most unhealthy air in the country. The California Air Resources Board has launched a program to clean up the valley’s toxic atmosphere.

Poverty is also an issue. The unemployment rate in the valley counties was between 6 percent and 9 percent in 2019, well above California’s average of 4 percent. Those rates started to decline as the economy picked up in 2022 but were still higher than the state average. The poverty rate for the valley was listed as 24 percent in 2020. Part of the problem is farmworker wages. The average annual salary for farmworkers was slightly more than $26,000, less than half of the state average of $59,000.

Many of the workers are undocumented, so the fear of deportation hangs over the fields.

They also face an array of health issues. Migrant field workers have a higher risk of contracting infectious diseases, respiratory ailments and parasitic infections due to their working conditions.

Getting proper health care can also be a struggle. Many farmworkers don’t have health insurance and those living in the United States illegally are reluctant to go to a medical facility over concerns of being deported.

This story isn’t confined to the Central Valley.

There are an estimated 2.5 million farmworkers in the United States. About 77 percent of them are Hispanic. They work in the vast acreage in the Midwest as well as in rural towns in the South.

They all face the same issues: low wages, health hazards and substandard working conditions. About 30 percent of farmworkers live in poverty. They have less access to healthcare than the general population as well as a shorter lifespan.

In September 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom signed a law that makes it easier for farmworkers to vote in union elections. Supporters say that will help the workers get better wages and working conditions.

Even with all the hardships, as you travel through the Central Valley, you still see farmworkers bent over in fields on both sides of the freeways and highways. Picking, raking, weeding, watering.

This back-breaking work is what brings food to your table and makes the Central Valley the productive region that it is.

The Big City in the Valley

Fresno is no small town.

It has 540,000 people, making it the 5th most populous city in California ahead of Sacramento, Long Beach and Oakland.

It’s located near the geographic center of California, close to the halfway point between Bakersfield and Sacramento.

Due to its size and location, Fresno is home to a number of federal and state government office buildings. The city is also considered a gateway to Yosemite Valley 60 miles to the east.

Fresno County is an agricultural powerhouse.

It contains almost 1.9 million acres of farmland, nearly half of the total land in the county.

The farmers here produce more than 350 different types of crops that are worth $8 billion, among the top agricultural counties in the country.

The top crop is almonds, followed by grapes, pistachios and poultry. About 99 percent of the nation’s raisins come from the Fresno area. In fact, raisins are so associated with the city that in 1986 CBS aired a six-episode comedic mini-series starring Carol Burnett called “Fresno” that centered on two local families fighting over the raisin industry.

About 20 percent of jobs in the Fresno area are related to agriculture, so the area is home to many farmworkers. About 50 percent of Fresno residents are listed as Hispanic or Latino with 25 percent classified as white and 14 percent as Asian.

The median annual household income is $63,000 and even with the median price of a home at under $370,000 it can be a struggle to make ends meet.

In October 2021, plans were announced to open the state’s largest family shelter to help the estimated 4,000 people in Fresno who are homeless. The facility is on the site of the old Sierra Hospital campus. It has room for 77 families as well as office space, a coffee shop and a church. The initial phase of the project opened in January 2024.

In addition, the mayor announced in August 2023 that the city is receiving nearly $44 million in infrastructure grant money to upgrade the downtown and Chinatown areas.

Fresno does have its place in history.

The city is home to what is generally considered the first modern landfill in the nation. The Fresno Sanitary Landfill was the first such facility to use trenching, compacting and daily trash burial.

Fresno is now the 5th most populous city in California.

It opened in 1937 and closed in 1987. The dumping ground began as a 20-acre site and grew to 140 acres. During the height of its operation, the landfill disposed of about 16,500 tons of waste a month. Over the years, it buried nearly 80 million cubic yards of trash.

All that garbage had its environmental consequences. In 1989, the property was declared a Superfund site due to concerns over methane gas and groundwater contamination from paint and other discarded items. The initial federal clean-up cost more than $38 million.

The former landfill, which is located three miles southwest of downtown Fresno, is now a National Historic Landmark and is on the National Register of Historic Places. A rare feat for a Superfund site.

Fresno is still breaking ground in the trash disposal industry.

The city is home to a large facility owned by the ERI recycling waste company. Inside the complex, about 6 million pounds of discarded electronic devices such as smart phones and tablets are disposed of every month. The process involves shredding the outdated items into piles of copper, aluminum and steel as well as removing hazardous components such as lithium batteries. ERI, which is based in Fresno, has eight facilities across the country that recycle 275 million pounds of electronic hardware every year. Those sites will remain busy in the years ahead in a society where people seem to want a new updated electronic gadget every year.

Fresno also has its place in credit card history.

Bank of America launched the nation’s first general purpose credit card in Fresno in September 1958. That month, the bank mailed 60,000 BankAmericards to Fresno residents who were BofA customers.

Bank officials chose Fresno because its population of 250,000 at the time was a good test market and 45 percent of residents had BofA accounts. In addition, if the experiment failed in a town like Fresno, bank officials figured most of the rest of country wouldn’t notice.

The credit limit on these original cards ranged from $300 to $500 with a monthly interest charge of 18 percent. The bank snared 6 percent of every purchase, but 300 merchants still signed up.

Three months later, BofA mailed out more cards to Modesto and Bakersfield. By October 1959, there were 2 million BankAmericards circulating in California. There was one major unexpected problem. The bank had estimated the delinquency rate on monthly payments would be 4 percent. Instead, it was 22 percent. There was also a high level of fraudulent charges.

At first, BofA suffered financial losses, but by the early 1960s, the new credit card was sailing ahead. In 1976, BankAmericard was changed to Visa and the rest, as they say, is history.

Oil and Country Music

Along Highway 99 south of Fresno are a collection of agricultural-based communities.

Among them are Visalia, McFarland and Delano, a 51,000-person town where the United Farmworkers Union was formed in 1965 in the Filipino Community Cultural Center that still stands today. More on that historical labor movement in a bit.

Farm fields continue to dominate the landscape here. Kern County is almost the equal of Fresno County when it comes to agriculture. Citrus trees and grape vines as well as acres of carrots, cotton and alfalfa are visible.

Nearly two hours after leaving Fresno, however, the scenery begins to change as we hit Bakersfield at the southern edge of the Central Valley.

One of the first things you notice is all the oil rigs to the east. Hundreds of them.

The oil fields on the northern edge of Bakersfield, California, are one of the primary drivers of the city’s economy.

Bakersfield is a town that was built on oil.

The Yokut tribe lived in this region for thousands of years, but settlers began to arrive after gold was discovered in Kern County in 1851.

The influx of new residents really took off in 1865 when oil was discovered. A settlement sprung up along the Kern River. One of the homes was owned by Thomas Baker from Ohio. He sold alfalfa from his farm. His stopover was called, yes, Baker’s Field.

The town grew quickly as people emigrated from Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma and other states to work in the oil fields. The railroads arrived in 1874 and another discovery of oil near the Kern River just north of town in 1899 fueled even more growth.

The boom continued for most of the 1900s and into this century. The population of Bakersfield grew from 70,000 in 1970 to its 413,000 today.

In fact, Kern for years produced more oil than any other county in the United States. In 2016, it was reported the county’s wells were responsible for 70 percent of California’s oil and 10 percent of the oil produced nationwide. Oil is so big here that the mascot for Bakersfield High School is “Danny Driller.”

In recent years, however, the oil industry has begun to slip in the Bakersfield area along with the rest of California’s oil production,.

The decline has left many oil fields unused or even abandoned. In California, it’s estimated that more than 100,000 oil wells now sit idle. Those static wells still release toxic emissions and gases. That can pose a danger for the 350,000 Californians who live within 600 feet of unplugged wells. More than 40,000 of those inactive wells are in Kern County. In July 2023, state officials said they are looking into plugging 100 abandoned oil wells in Kern County, many of which are leaking methane.

Despite these idle wells, Kern County officials in March 2021 approved a policy that will streamline the approval of drilling projects. The new system could open the door for 2,700 new oil and gas wells per year. The new rules have drawn criticism from clean energy advocates as well as environmental activists.

Despite all these issues, 13,000 people in Kern County work either directly and indirectly in the oil industry.

The decades of emissions from working oil wells as well as agricultural products has left Bakersfield with some pretty unhealthy air. In November 2022, the American Lung Association named Bakersfield as having the worst air quality of any U.S. city. Fresno and Visalia were right behind.

Vince Galindo performs at the Crystal Palace in Bakersfield on March 18, 2022

It’s not all doom and gloom for the Bakersfield economy.

The city has started to grow its manufacturing base with factories that produce products such as central vacuums and house paint as well as the Dreyer’s ice cream manufacturing plant that was expanded in 2006 into what the company claims is the largest ice cream factory in the world.

There’s also been a move to attract more younger residents with more youth-centered businesses and jobs. A revitalization of the downtown is also aimed at millennials.

Before we leave town, it’s appropriate to discuss Bakersfield’s role in country music history. The town has its own country style that’s been labeled “Bakersfield Sound.”

One of the originators was Buck Owens, who moved to Bakersfield with his new wife in 1951. Owens, along with Merle Haggard and Dwight Yoakam, helped popularize the country music subgenre that’s driven by electric guitar. Yoakam and Owens even collaborated on a 1988 song “Streets of Bakersfield” a duet that became Yoakam’s first number one hit.

A statue of singer Buck Owens inside the Crystal Palace in Bakersfield, California.

Haggard was another local boy. He grew up in the Bakersfield area and recorded his first single with Talley, a small local record label.

To commemorate the city’s music history, Owens built the Crystal Palace music hall in 1996. The square building on Buck Owens Boulevard contains a restaurant with a large music stage as well as a museum and statues of a variety of country music stars. Its decor resembles an old western town.

The venue was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, closing in March 2020 and not reopening until November 2021. In March 2022, the Palace was slowly getting back to normal, hosting dinner and music nights on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. The Palace was nearly full when we visited on a Friday night that month. Families, couples, large groups and even a birthday party for a teenage girl were among the crowd.

Mathy Hufford, the general manager of the Palace, told 60 Days USA the restaurant was drawing large crowds as the pandemic eased and everyone was pretty happy, “It’s so good to be open again,” she said.

On this night, Ron and Brenda Woodward were enjoying their visit to the Palace with their son, Jim. They had traveled from Michigan to see Jim’s new baby, born just 3 weeks earlier.

Both are country western music fans but noted you don’t have to be to enjoy the food, ambiance and scenery.

Jim said he brought his parents here for one simple reason.

“It’s the best place in Bakersfield,” he told 60 Days USA.

High Points in the High Desert

The scenery changes quickly as we head east out of Bakersfield on Highway 58.

It’s more mountainous and greener. There are even some pine trees.

The high desert region of California is a somewhat forgotten area of the state. However, it is full of fascinating places and rich history.

In a half-hour, we’ve risen from an elevation of 400 feet in Bakersfield to 2,600 feet in the foothills of the Tehachapi Mountains.

Our first stop is Keene, a town of 400 people nestled in the lower mountains.

The community really wouldn’t be notable except it’s the place where United Farmworkers co-founder Cesar Chavez lived the final 20 years of his life until his death in 1993 at the age of 66.

The town has been the headquarters for the agricultural labor union since the organization moved its offices here from Delano in 1972. The headquarters are part of the 187-acre National Chavez Center, which includes a visitors center, a memorial center and Chavez’s gravesite.

A big part of the site is the Cesar Chavez National Monument, which encompasses 112 acres with 26 historic buildings that include the UFW’s former headquarters.

The monument was dedicated in 2012 with a visit from President Barack Obama. It was the first national park to honor a contemporary Latino American.

There’s good reason that Chavez was the first to receive that honor.

Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona, in 1927. His family moved to California in 1938 where they worked in farm fields all over the central part of the state.

After serving two years in the Navy, Chavez married Helen Fabela and they settled in Delano in 1948. They would eventually have seven children.

Chavez started his career in activism by helping register voters. In 1962, he founded the National Farm Workers Association. He traveled up and down the Central Valley, recruiting members.

In 1965, farmworkers were making about $1 an hour. They were no toilets in the fields and drinking water was sometimes scarce. The average lifespan of a farmworker then was 49.

Chavez was joined by Dolores Huerta and the group organized labor strikes to secure higher wages for their members.

In September 1965, the mostly Filipino members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee struck nine farms. Chavez’s group joined the walkout. A consumer boycott of grapes was also organized. That was followed by a 25-day, 340-mile protest walk by workers to Sacramento.

Under public pressure, the growers eventually relented and signed union contracts.

In 1966, the NFWA and the AWOC merged. The new association organized another grape boycott in 1970 and increased its membership to 50,000 workers.

In 1988, Chavez completed a 36-day fast. The protest helped raise awareness of pesticides used in farm fields.

The graves of Cesar Chavez and his wife, Helen Fabela Chavez, in Keene, California

When Chavez died in his sleep in 1993 he was helping the United Farm Workers fight a lawsuit filed against the union by a Salinas-based vegetable and lettuce producer.

He is buried near a bed of roses in front of his office at the UFW headquarters in Keene.

During a visit by 60 Days USA in March 2022, Miranda Hernandez, a park ranger at the site, said one of the big impacts Chavez had was making Hispanic people proud of their heritage. She noted that when her grandmother was a child, she was encouraged not to speak Spanish at school and elsewhere.

“He stood up and he was a hero,” Hernandez said.

Jackie Hoyos, who started working at the gift shop a month earlier, said she heard similar stories from many visitors. A lot of them worked in the fields and even protested alongside Chavez. They come to pay tribute.

Hoyos said other visitors simply see the highway sign for the monument, recognize Chavez’s name and come out of curiosity. Others see the facility on a map while planning a road trip.

That’s what brought John and Trina Lee of Sacramento on this particular day. They noticed the national monument on the route they were drawing up and felt the need to come. Trina teaches English and many of her students are Hispanic.

“I’m an American and this is my history,” she told 60 Days USA. “I’m a Californian and this is my history.”

—————————————–

We continue east on Highway 58 with scenery changing again from the pine-covered mountains to a more desert-like landscape.

Just outside of Keene is the Tehachapi Pass Railroad Line, better known as the Tehachapi Loop.

The circular railway loop was built in 1875 and 1876 by 3,000 Chinese workers who had nothing more than picks, shovels and blasting powder.

The line’s 50 miles of track traverses the steep Tehachapi Mountains to an elevation of 3,600 feet. The loop is still in use today with more than 30 freight trains passing through daily. It’s considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Railroad World.

A little farther down the road is where another marvel, the Pacific Crest Trail, crosses under Highway 58 before it heads up the slopes of the southern Sierra Nevada. A gate on the north side of the roadway was where Cheryl Strayed began her 94-day hike in 1995 that eventually led to her book, “Wild.” My friend, Mark Shuman, and I found this gate in 2016 and hiked the first mile and a half of Strayed’s route.

About 10 miles farther down the highway is the town of Mojave, a community of 3,800 people now known for its strong winds and its significance to the aerospace industry.

The town was settled in 1876 as a construction camp for the Southern Pacific Railroad. From 1884 to 1889, Mojave was the western terminus of the 165-mile, 20 mule team borax wagons from Harmony Borax Works in Death Valley.

The community also served in the early 1900s as the headquarters for the construction of the 223-mile water pipeline project from the Owens Valley on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada to the growing metropolis of Los Angeles, a scheme made famous in the 1974 film “Chinatown.” Some of those pipelines still travel underground through Mojave.

Today, the town is home to two more modern industries.

The first is the Alta Wind Energy Center. This facility takes advantage of the area’s high winds to produce 1,550 megawatts of electricity for Southern California Edison. It’s the third largest onshore wind farm in the world, although two larger wind projects are currently under construction in Iowa and the United Kingdom.

The Mojave Space Port in the High Desert of California is home to some groundbreaking aerospace design companies.

The second major industry here is the Mojave Air and Space Port, a 3,300-acre complex with three runways that was the first facility in the United States to be licensed for horizontal launches of reusable spacecraft. It was certified by the Federal Aviation Administration in 2004 as a spaceport.

It’s home to 60 companies that are involved in flight research, advanced aerospace design and other entities. Several of the firms are developing rockets that are designed to eventually take private citizens into outer space.

The airfield’s first success came in September 2004 when the Mojave-based SpaceShipOne was launched in mid-air over the spaceport and ascended to an altitude of 64 miles for three minutes before gliding back to Earth. The 28-foot-long plane became the first privately funded aircraft to soar above the Earth’s atmosphere. It made 17 flights in all, reaching outer space on its 15th voyage.

In February 2019, Virgin Galactic completed a successful test flight from the Mojave airfield of its VSS Unity aircraft. Virgin’s goal is to carry private citizens on recreational flights into outer space.

Stratolaunch is another company at Mojave looking toward the future. In April 2019, it completed a successful test flight of its Roc plane, the largest aircraft ever built. That spacecraft is capable of launching satellite-carrying rockets.

There are no public tours given at the Mojave spaceport, but the facility hosts a “Plane Crazy Saturday” on the third Saturday of every month.

On Saturday, March 19, 2022, we paid a visit to the spaceport to watch several dozen people mingle among the vintage planes. The license plates in the parking lot indicated there were tourists from Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, Illinois and Oregon among the Californians there.

One of them was Bill Frost, a former member of the Air Force as well as a Vietnam War veteran and a resident of nearby Tehachapi. He’s visited the spaceport dozens of times over the past two decades. On this day, he had family members with him.

“You always see so many different things,” the airplane enthusiast told 60 Days USA.

Blanca MacDougal sees that enthusiasm working as a waitress at the Voyager restaurant at the site. She told 60 Days USA that the spaceport visitors are always happy and interested in what’s going on.

Todd Lindner, the spaceport’s chief executive officer, said the facility is also a way to connect with the community and teach them about aviation history.

“We want them to know what they have right in their back yard,” Lindner told 60 Days USA.

—————————————–

As we continue east on Highway 58, we get a glimpse to the south of Edwards Air Force Base, another aeronautical gem in the high desert.

The 470-square-mile facility is the second largest Air Force base in the country with 19 runways. One is almost three miles in length, making it the longest runway in the nation.

The Rogers Lake bed was converted to military use in 1933. The base is where pilot Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947. Most modern military jets have been at least partially tested here. The space shuttle programs did their tests here, too. The 1981 landing of the shuttle Columbia was the first time an orbiting space vehicle had returned safely to Earth.

As Edwards AFB fades from view, we come across the town of Boron.

This community of 2,400 people that straddles Highway 58 is here for one reason: The borate mines that are clearly visible from the highway as you approach town.

This mineral is used to manufacture the compound known as borax. It may not sound interesting, but the borax here is used in more than 30 types of products ranging from detergents to soap to adhesives to glass to liquid fertilizers, mostly under the 20 Mule Team Borax brand.

In addition, lithium has been discovered in boron waste piles, advancing the possibility that the mineral could be used in electric car batteries.

This varied usage has made borate mining quite sustainable in the high desert. The Rio Tinto U.S. Borax Mine is 1.7 miles wide, 2 miles long and more than 700 feet deep, making it the largest open pit mine in California and one of the richest borate deposits in the world.

The mine produces 1 million tons of refined borate ore every year, providing about a third of the world’s demand for the compound. The ore reserves are expected to last until 2050.

About 1,000 people are employed at the Rio Tinto mine, although they aren’t necessarily getting rich. The median annual household income in Boron is $54,000, well below California’s median of $91,000. About 25 percent of residents live below the poverty line, including a high percentage among the Hispanic and American Indian populations. On the plus side, you can buy a single-family home for about $145,000.

Borax ore was first discovered here in 1913. Open pit mining began in 1957.

Many people in town today are descendants of Oklahomans who migrated to this region during the Dust Bowl days of the 1930s to work in the mines.

All this history is captured at the Twenty Mule Team Museum, which sits at the corner of Boron Road and Twenty Mule Team Road near the center of this quiet, dusty town.

—————————————–

Just 10 miles down the road is Kramer Junction, a small town that until recently was known for traffic jams and deadly vehicle crashes.

That’s because the community is where Highway 58 and Highway 395 intersect. For decades, that juncture was a four-way intersection with stop signs and then later stoplights. It was described by local journalist and long-time resident Bill Deaver as a “death trap.”

That all changed in October 2019 when a new Highway 58 bypass opened, circumventing the dangerous intersection and bringing relief to this former Southern Pacific Railroad town.

As we glide out of Kramer Junction, it should be noted that we are now in San Bernardino County. At 20,105 square miles it is the largest county in the continental United States. The county is actually bigger than the nine smallest states in our country. It should also be noted that 82 percent of the acreage in this large county is undeveloped.

Speaking of vacant land, we now approach the town of Hinkley.

Most people wouldn’t know the community by name, but it’s the town made famous in the 2000 film, “Erin Brockovich,” starring Julia Roberts.

Brockovich, a legal assistant for a Los Angeles law firm, took Pacific Gas & Electric to court in the 1990s for contaminating Hinkley’s groundwater with the cancer-causing chemical hexavalent chromium.

One of the many abandoned homes in Hinkley, California, the town made famous by Erin Brockovich.

The chemical came from PG&E’s Hinkley Compressor Station, which was used to transport natural gas from Texas to Northern California. Hexavalent chromium was used from 1952 to 1966 to fight corrosion on the station’s equipment.

With Brockovich’s persistence, PG&E eventually agreed to a $330 million settlement with 633 Hinkley residents in 1996. Since then, PG&E has spent $700 million cleaning up the environmental mess.

The town, however, did not flourish from its cash infusion.

A lot of residents sold their houses at discount prices and moved, still afraid of the poisonous groundwater.

In the past two decades, PG&E has purchased 300 homes and bulldozed them. The utility has planted 230 acres of alfalfa, rye and other grasses on the vacant land.

The elementary school closed in 2013. The post office was shuttered in 2015. The town’s last remaining store also boarded up in 2015.

Hinkley’s population is listed as 917, although they must be counting the dogs, cats and chickens to reach that number.

Residential streets such as Mulberry Avenue are dotted with abandoned homes and empty lots. The school building still stands, but it is decaying.

Erin Brockovich is now a famous consumer activist still fighting for environmental causes.

But the town of Hinkley is no more.

————————————–

Right next door to Hinkley is the community of Barstow.

This town of nearly 25,000 people sitting at 2,106 feet elevation was established in the 1860s and 1870s with the discovery of gold, silver and other minerals in the nearby Mojave Desert.

The Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in 1882, helping develop the town into a transportation center. A large rail yard owned by Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway sits on 600 acres with 48 classification tracks. Southern Pacific’s transcontinental line from Chicago has a major fork in this yard. One spur travels west to Los Angeles. The other heads north to San Francisco.

Barstow’s population is listed as nearly 52 percent Hispanic or Latino. The median household income is $52,000 per year and 22 percent of the town lives below the poverty line.

One of the things you notice as you roll into downtown Barstow is the Route 66 signs on poles along the main roads. The town takes pride in being one of the main stops on that once prominent highway from Los Angeles to Chicago.

The Route 66 museum in Barstow, California.

The Route 66 Mother Road Museum was opened in 2000 in an old hotel. It is literally a wall-to-wall display of artifacts and photographs from Route 66’s glory days.

During a visit by 60 Days USA in March 2022, the retired gentlemen working behind the counter said the museum gets visitors from all 50 states as well as other countries, many of which have Route 66 organizations. He said the foreign visitors seem particularly fascinated with the old highway. The road has special meaning for him as his family used to take Route 66 from Barstow to visit family in Missouri when he was a child.

We’ll have more to say about this historic roadway and its significance when we travel through Arizona tomorrow.

The Long, Dry Road to Needles

You have two highway choices as you head east out of Barstow.

One is Interstate 15, a not-too-scenic roadway that takes you past the entrance to Death Valley and eventually into the gambling mecca of Las Vegas.

Right before the Nevada border is the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System. The facility contains three solar power plants on 3,500 acres that’s been generating 386 megawatts of electricity for PG&E and Southern California Edison since it opened in 2013.

Ivanpah is the world’s largest solar thermal plant and its 347,000 sun-tracking mirrors are clearly visible from the freeway as you cruise by.

The complex is a major reason that California is by far the number one solar energy state, producing 29 percent of the nation’s output. Texas is second, Florida is third and Arizona is fourth. However, it might surprise you which state is fifth. We’ll discuss that state’s solar energy industry when we pass through in a couple weeks.

Your second option as you depart Barstow is Interstate 40. It begins where Highway 58 ends.

The first town you hit is the place where California’s solar energy industry got its start.

Daggett was the site of the world’s first commercial solar power plants. Solar Energy Generation System 1 and Solar Energy Generation System 2 began operations in 1985. One reason this 700-person community was selected for the solar complex is that it receives 340 days of sunshine a year.

The two systems are now part of nine solar power plants in three locations in the region that can generate up to 354 megawatts of electricity, enough power for 232,000 homes.

There’s plenty of sunshine as we motor eastward on Interstate 40. It’s two hours to Needles and there’s not much in between here and there.

Interstate 40 is the third longest freeway in the United States at 2,555 miles. It begins in Barstow and travels all the way to Wilmington, North Carolina, passing through eight states along the way.

There’s a sign just outside Barstow informing you it’s 2,554 miles to Wilmington. There’s another one outside Wilmington telling you the same thing in the other direction. Both locations have had those signs stolen numerous times.

—————————————-

The Needles area was originally inhabited by members of the Mojave tribe, who used the Colorado River to fish and irrigate crops. The Fort Mojave Indian Tribe is still headquartered in Needles.

The town was founded in 1883 as a place for the construction workers of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad who were building a bridge across the Colorado River.

At one time, Needles was the largest stop on the river north of Yuma, Arizona. It also was a swapping station for freight trains headed to and from Los Angeles.

In the 1930s, the Colorado River crossing was where many Dust Bowl refugees first entered California. Needles, in fact, is the Joad family’s first stop in John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Transportation and warehousing were the major industries in Needles for a long time, but there had been some economic struggles in recent decades.

The railroad industry dried up. Route 66 no longer brings in the traffic it once did. The long-standing Claypool’s Hardware store closed in 2002. A few years later, Mudshark Pizza followed. The town lost Bashas’, its last full-fledged grocery store, in 2014.

In 2012, the city decided to see if the cannabis industry could revive the local economy. Voters overwhelmingly approved a 10 percent tax on cannabis businesses. Starting in 2015, city officials have approved more than 80 permits for cannabis-related businesses.

Marijuana cultivation was aided by the nearby Colorado River water and cheap electricity from a city-owned utility. Growing operations sprung up in old facilities on almost every block. So did places to bake edible cannabis treats as well as manufacture cannabis oils.

By 2018, four stores had opened in Needles to sell cannabis to the public, two years after California legalized recreational marijuana.

In July 2019, city leaders told The Sun newspaper that the cannabis plans were working. The 10 percent tax had added $1.2 million to the city’s $5.5 million budget. More than 350 new jobs paying on average $20 an hour had been created.

City Manager Rick Daniels told 60 Days USA in March 2021 that there were 160,000 square feet of cannabis-related businesses operating in town. There was another 640,000 square feet approved. In October 2021, the planning commission approved conditional use permits for a cannabis store despite objections from some local residents about its downtown location. In February 2022, the council did deny a permit application for a cannabis business on North L Street due to concerns from nearby residents.

Daniels pointed out that the local cannabis businesses had now created 500 new jobs. That’s in a town that had a total of only 2,000 jobs when this all began.

During a March 2022 visit, we stopped by the Marvin’s Mary J dispensary on the Old Needles Highway. Jeff, who was one of the people working the counter inside, told 60 Days USA, that business has been booming for the five dispensaries operating in Needles.

He noted Marvin’s sales are exclusively for recreational use for people 21 years and older. A large portion of the customer base skews to an older demographic and the shop gets a number of visitors from nearby Nevada and Arizona.

You can only purchase cannabis products at Marvin’s. You can’t consume the product in the dispensary or outside in the parking lot.

That’s not the case at a cannabis lounge at an old Texaco gas station across the street. There, people are able to use cannabis on site. That facility, known as Kush on 66, opened in June 2022.

Needles isn’t the only locale giving this new industry a try.

In the United States, there are only 4 states left where the cannabis industry is “fully illegal.” There are 23 states, including California, where cannabis is fully legalized.

In 2019, legal cannabis retail sales nationwide topped $10 billion. About 60 percent of those transactions were for recreational use. Sales in 2020 were estimated at $15 billion. Not even COVID-19 could slow the industry down. Sales hit $25 billion in 2021 with 100,000 new jobs added. In 2022, sales topped $30 billion. Sales topped $33 billion in 2023.

There are still issues for the industry to tackle. A big one is banking. Many financial institutions still refuse to deal with cannabis-related businesses.

In California, cannabis manufacturers and merchants have also had to deal with high taxes, strict regulations and a large illicit market.

There are also growing concerns about the increasing potency of cannabis and how the drug may now be addictive.

Nonetheless, the cannabis industry has a healthy upward trajectory and the economic lift is welcome news in a town like Needles, which is still battling to bounce back. During a visit by 60 Days USA in March 2022, it was evident there remains a lot of vacant businesses and others that are struggling.

The cannabis dispensaries did seem to be thriving as were the hotels.

Mayor Janet Jernigan, a Farmers insurance agent as well as a member of the Needles Tourism and Visitors Center, notes that the Colorado River is also a big draw here.

She also said they are trying to revive interest in historic Route 66. The roadway is still the main drag in Needles.

Her tourism center helped other jurisdictions with the 2021 edition of the Route 66 passport book, a souvenir that allows people to collect stamps to document their trip along the old highway.

The Wagon Wheel restaurant in Needles, California, is a favorite of locals as well as tourists.

Her center is also a major participant in the annual Route 66 Bike Week, which takes place in April. Over the course of five days, motorcyclists rode the old highway from Needles to Seligman, Arizona. There’s music, campfires and games along the way.

Jernigan grew up in Needles. She and her husband also raised their daughter here. In November 2022, she was chosen as the city’s mayor. She told 60 Days USA that there is freedom and friendship in this eastern California town that she enjoys. The town supports its local youth sports teams and there is plenty to do.

“It’s really never boring,” she said. “The heat during the summer is the negative part, but the winters here are great.”

Daniels and his wife moved to Needles a decade ago after spending 25 years in the Palm Springs area. He too is sold on the attributes of the town.

“I love being here because it’s quieter. It’s calmer,” he said. “That background hum that’s always in urban areas is missing here.”

He notes there’s no waiting in line here, even at the local DMV office. In fact, Daniels says people from Los Angeles will drive to the Needles DMV because it’s so much easier to navigate.

And if you do get bored, he notes, Las Vegas is only 90 minutes away.

Daniels and Jernigan are both frequent visitors to the city’s Wagon Wheel restaurant, a favorite of travelers as well as locals. The pot roast is apparently the specialty and was still a highlighted menu item when 60 Days USA visited the packed restaurant on a Saturday evening in March 2022.

That’ll wrap it up for Day 1. Plenty of open road on tap for tomorrow.

On Day 2, we begin and end at a pair of famous hotels with a drive on the longest stretch of the old Route 66 still left in the country.