Day 12: Blowing Through the Bayou

March 31, 2021

Day 10: Cars, Cookbooks, Oil and Music

March 29, 2021Most recently updated on March 11, 2024

Driven on April 1, 2023

Originally posted on March 30, 2021

Today is the day we leave the Southwest and begin our 12-day journey through the country’s southern states.

We start our sojourn by driving in a southeasterly direction out of Tulsa through suburbs such as Broken Arrow.

Eventually, we glide into more open country and merge onto Highway 351, also known as the Muskogee Turnpike.

After 45 minutes, we roll into Tullahassee, a town of 112 people that is part of an important story in U.S. history.

Tullahassee is the oldest of the 13 All Black Towns still existing in Oklahoma.

It was founded in 1850 by members of the Creek Nation who built a school at the site. In 1881, the tribe handed over the town to recently emancipated Black Freedman who had been slaves of the Five Tribes nation.

Yes, you read that correctly.

In the 1800s, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole tribes all owned Black slaves. As early as the 1500s, European explorers convinced Native Americans to enslave members of other tribes as a means of free labor.

The inter-tribal slave trade faded in the 1700s but was soon replaced by the enslavement of Africans captured and brought to this country. At that time, the five tribes had already started to adopt some European traditions such as clothing and governmental structure.

So, it wasn’t a stretch to pick up the European system of slave owning.

This was heightened when Native Americans were forced off their land in the 1830s and moved to Indian Territory locales such as Oklahoma. The tribes needed the free labor to help them with their crops, in particular cotton.

It’s estimated that in 1860 the Cherokee tribes in Indian Territory owned 2,511 Black slaves, about 15 percent of their population. The Choctaw held 2,349 slaves, about 14 percent of their population. The Creek enslaved 1,532 Black people, about 10 percent of their population. The Chickasaw owned 975 slaves, about 18 percent of their population.

Most of the slave owners were the wealthiest members of their tribes. Some even had estates that resembled plantations. Tribal laws restricted the movement of enslaved people and prohibited them from learning to read and write as well as forbade interracial relationships.

After the Civil War, treaties signed by the tribes and the U.S. government in 1866 freed slaves who had been held on Native American land. However, the native tribes did not view the slaves as citizens of their nations. So, they sent many of them packing.

That brings us to Tullahassee in 1881. That’s when a group of these newly emancipated Freedman landed at this site. They formed an All Black Town. These were places recently freed slaves congregated to form their own communities.

They did so for protection and economic security. Many of these settlers created farming communities that sustained themselves. They built schools, churches, homes and businesses.

Between 1865 and 1920, African-Americans created 50 All Black Towns in Oklahoma, where many Black settlers felt they could escape the prejudice and violence in the South.

It worked that way for a while.

However, after Oklahoma became a state in 1907, Jim Crow laws were passed and the state began to infringe on the All Black Towns.

The Great Depression in the 1930s decimated the agricultural communities and many residents migrated to the Midwest, West and even the Canadian Plains looking for opportunities.

Many of the All Black Towns disappeared.

Tullahassee is one of the few to survive.

About 72 percent of the town’s residents are listed as Black. The average age is 57 and the median household income is listed at $108,000.

Tullahassee is now one of a number of towns that is seeking reparations for the harms done to Black populations through the Mayors Organized for Reparations and Equity (MORE) organization.

Local residents also launched a campaign in February 2024 for their town to have their own ZIP code, a status they lost about 20 years ago.

Entering Arkansas

Out of Tullahassee we continue south on Highway 351.

We pass by the town of Muskogee, made famous by Merle Haggard’s 1969 country music hit “Okie from Muskogee.” It’s a song he said he wrote against the people who were protesting against the Vietnam War.

About a half-hour later, we meet up again with our traveling companion Interstate 40. We head east on this coast-to-coast freeway through the eastern flatlands of Oklahoma.

As we approach the Arkansas border, the landscape changes dramatically. The rolling hills become greener and pine trees become plentiful. A few swamps even appear.

After about an hour, we finally leave the Southwest and cross the border into Arkansas, the first of many segments of our Southern journey.

The Natural State, as it’s nicknamed, is the 33rd most populous state with slightly more than 3 million people. Arkansas has only eight cities with more than 60,000 residents.

About 71 percent of the state’s citizens are white with 15 percent Black. The annual median household income is about $56,000, one of the lower levels among states.

The economy here took a severe hit after the Civil War due to the state’s reliance on plantations and slavery. It diversified a bit after World War Two, relying now on agriculture, steel, the aircraft industry and tourism. It’s among the top states in rice, broiler chickens and turkeys.

There are five Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Arkansas. They’re led by Walmart, which still sits at the top the standings. Also on the list are Tyson Foods, Murphy USA, J.B. Hunt Transport Services and Dillard’s.

The scenery in Arkansas is quite varied.

It ranges from the mountainous Ozark region in the northeast to the dense forests in the southern timberlands to the low-lying areas along the Mississippi River.

Our route the next two days will take us through most of that geography.

As soon as you cross the state line, you roll into Fort Smith, the first official stop on the southern leg of this journey.

At 90,000 people, Fort Smith is the third most populous city in Arkansas. Almost 60 percent of the residents here are white and nearly 20 percent are listed Hispanic or Latino.

As its name implies, the city’s history is closely tied to its forts.

Original settlers found the soil conducive to farming and the high bluff along the river a good defensive lookout against invaders.

Fort Smith was built in 1817 to help keep the peace between the Cherokee and Osage tribes. The fort was abandoned in 1824, but by then a town had started to grow up around it.

The economy was initially centered around the fur trade. It then became a regional trade center after the railroads arrived in the 1870s. In later years, it became a regional manufacturing center.

The 1824 closure of Fort Smith didn’t last long. It became active again during the 1830s when the “Indian removal” era was in full force. The fort was put to use once more in the 1840s during the United States’ war with Mexico.

During the Civil War, the fort was initially occupied by Confederate soldiers, but Union troops seized it in 1863.

Fort Smith was vacated by the military for the final time in 1871. Over the decades it was used for various other purposes and is now home to the Fort Smith National Historic Site.

Another fort played a significant role in the town’s history.

Fort Chaffee was established near Fort Smith during World War Two. In the 1970s, the facility became a relocation center for Vietnamese refugees. In the 1980s, it served the same purpose for Cuban refugees. The Arkansas National Guard now uses the fort as a training facility.

Military operations are still a key part of the economy. In June 2021, the federal government announced that Fort Smith has been selected as a pilot training center for F-35 and F-16 fighter jets.

A famous figure in U.S. history is connected to Fort Smith.

Isaac Parker was appointed as a judge here in 1875 to bring law and order to a town full of saloons and brothels.

Parker did just that.

Before he retired in 1896, he had sentenced 160 people to death and 79 of them were actually executed, some of them hanged at Fort Smith.

Parker was known as the “Hanging Judge,” a title he appears to have earned, although he did tell an interviewer in 1896 he was actually against capital punishment but followed the law while he was a judge.

As part of this law and order history, Fort Smith opened the doors on the United States Marshals Museum in September 2019. The mission of the 53,000-square-foot facility is to chronicle the history of the U.S. Marshals as well as to “inspire appreciation for the accomplishments” of the service.

The U.S. Marshals program was established in 1789. The agency’s roles have included assisting courthouse proceedings, tracking down fugitives and helping manage operations for disaster relief. During the country’s expansion in the 1800s, marshals were called upon to enforce law and order in the western frontier. Today, they oversee the federal Witness Protection program. More than 350 marshals have been killed in the line of duty since the agency’s formation.

The Spirit of the American Doughboy Monument in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

The town also pays homage to its military history with its Spirit of the American Doughboy Monument, which honors World War One soldiers. The Fort Smith sculpture is one of two in Arkansas and one of 136 such memorials in 35 states.

“Doughboys” was the nickname given to U.S. soldiers who fought in Europe during World War One. The exact origin for the term isn’t known, although several theories exist. One is that the name stems from U.S. soldiers in the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, whose uniforms appeared to be covered in dough after they marched through dusty fields.

The country’s last Doughboy soldier from World War One was Frank Buckles. He died in 2011 in West Virginia at the age of 110. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

The Fort Smith monument was dedicated on July 4, 1930, in front of a crowd of 2,000 people. The statue was placed in storage in 1979 after it was vandalized. It was refurbished and rededicated at a new site in 1989.

Spinach and Gators

We head east on Interstate 40 as we depart Fort Smith.

This part of the freeway overlaps with U.S. Route 71, a 1,515-mile road that runs north to south through the center of the country.

Highway 71 starts in southern Louisiana near Baton Rouge and travels all the way to International Falls, Minnesota, at the Canadian border. It passes through six states. They are Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, Missouri, Iowa and Minnesota, although the roadway is in Texas for only about three miles.

Highway 71 is sort of like a north-south version of Route 66.

The biggest towns it travels through are Shreveport, Louisiana, Texarkana, Texas, Fort Smith and Kansas City. The rest of its route cuts through small towns and rural communities.

It was built in 1926 and its original path hasn’t changed much, although it does merge with other highways and freeways along the way now.

—————-

After 20 minutes on this particular stretch, Highway 71 veers north and we say goodbye as we stay on Interstate 40.

We immediately cross into the town of Alma.

We’re highlighting this community of nearly 6,000 people primarily for one reason – spinach. We’ll get to that in a moment. First, a little history.

The first Anglo settler to this region was Armistead “Ira” Smoot, who set up residence in 1836 and farmed the fertile land here. He was followed in 1872 by Colonel Mathias F. Locke, who built a house and a cotton gin.

Timber was one of the early industries. Alma was known as “Gum Town” because of its gum trees.

The town started to grow when a train depot was built in 1876 for the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad. Cotton and timber were the main commodities transported.

In the early 1900s, coal was mined and natural gas was tapped in the surrounding region.

However, it was agriculture that had staying power in the economy. The main crops included cotton, hay, strawberries, beans, tomatoes, mustard greens and, yes, spinach.

The spinach output sparked the canning industry here. The first in town was Alma Canning and Evaporation, which was formed in 1888.

During the Great Depression, spinach grew in popularity due to its cheap price as well as the introduction of the cartoon character Popeye the Sailor, who downed a can of spinach whenever he needed some extra muscle power. Popeye’s celebrity boosted the spinach industry in Alma and other locales.

The Popeye statue in Alma, Arkansas

The local industry experienced another surge during World War Two when Alma factories supplied canned goods to soldiers overseas. At one point, the Allen Canning Company in town processed 60 million pounds of spinach a year. Overall, more than half of the spinach canned in the United States came from Alma.

In 1961, H. L. Hunt purchased Alma Canning Company. The manufacturer remains the leading business in Alma.

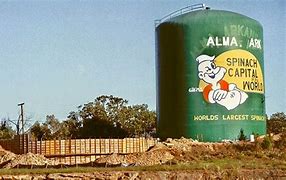

In 1987, Alma proclaimed itself the “Spinach Capital of the World.”

To cement its claim, the town erected a papier mache statue of Popeye in front of the Chamber of Commerce building. That deteriorated after a few years, so the city replaced it with a fiberglass statue. In 2007, that monument was replaced by a bronze statue of Popeye that sits atop a water fountain in the city’s Popeye Park downtown.

In 1991, local officials painted their resident water tower to look like a can of spinach with Popeye smiling down at motorists.

The city also hosts an annual Spinach Festival in April that includes a spinach eating contest and a “spinach drop.”

—————————————-

We head east once more on Interstate 40 with two hours of driving ahead until we reach the state capital.

The Arkansas River runs parallel to I-40 in this stretch of the state. It’s a river that probably doesn’t receive the credit it deserves.

It’s 1,469 miles long, beginning near Leadville, Colorado, in the Rocky Mountains and flowing all the way to the Mississippi River. It has a “total fall” of 11,400 feet from start to finish.

It’s the sixth longest river in the country and the second longest Mississippi tributary. The river travels through Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma and, of course, Arkansas.

The Arkansas River played a historic role in the westward expansion of this country as explorers followed its course upstream.

From 1820 to 1846, it was the boundary between the United States and Mexico.

The river still feeds the farmlands in the states it traverses. With the Port of Catoosa in Tulsa, Oklahoma, as its western terminus, the Arkansas also plays an important role as an inland waterway for commercial barge traffic.

The river also funnels into the Holla Bend National Wildlife Refuge.

The 7,000-acre sanctuary south of Interstate 40 was established in 1957 after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cut a new channel at a place in the Arkansas River where there was a “deep bend” to control flooding and promote navigation.

In the early 1900s, more than 60 families farmed the rich land there, but a 1927 flood covered the region with four feet of sand. The families picked up and moved elsewhere.

Today, the refuge’s lakes and ponds are the winter home for up to 100,000 migrating geese and ducks. Bald eagles can be seen from December to February. Egrets, herons and other birds have permanent homes here. The refuge is also the northern edge of the American alligator habitat.

Some of the land is still farmed and a portion of the crops are left out for the birds.

Segregation, Evolution and the Clintons

After passing the Holla Bend region, Interstate 40 bends southeast and takes you straight through the middle of Arkansas.

An hour later, you cross the Arkansas River and glide into the metropolis of Little Rock.

At slightly more than 200,000 people, the state capital is by far the most populous city in Arkansas. It’s a diverse community that is 45 percent white, 41 percent Black and nearly 8 percent Hispanic or Latino. It has an annual median household income of $58,000 and a poverty rate of 16 percent. The median home price is listed as about $200,000.

The name “Little Rock” is synonymous with school desegregation. It also played a lesser-known role in the teaching of evolution in public schools.

And, of course, it’s where former President Bill Clinton began his political rise after he was elected governor of Arkansas.

But let’s start at the beginning.

The Little Rock region was initially inhabited by Mississippi River native tribes for thousands of years.

A French explorer who scouted the area in 1722 named the settlement after a small rock formation in the Arkansas River that served as a navigation guide. The rock formation can still be seen from city’s waterfront.

The region became part of the United States after the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. The first permanent Anglo resident was a fur trader who built a cabin in 1812.

The first steamboat arrived in 1822 and the city was incorporated in 1835. Little Rock was named state capital when Arkansas was admitted to the Union in 1836.

Little Rock was captured by Union forces in 1863 during the Civil War and was under military control until the end of the conflict.

The railroads first came through in the 1880s. The city’s early economy was agriculture based with crops such as cotton and soybeans.

Since the 1950s, manufacturing has taken over as the main driver. That has become even more embedded since the Port of Little Rock opened in 1971. The docks are part of the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System that stretches 448 miles to the port in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Little Rock’s port is home to more than 40 businesses that employ more than 4,000 people.

One of those industries is a 158,000-square-foot facility owned by Hormel that manufactures Skippy Peanut Butter. Rail cars bring 750,000 pounds of peanuts every day to the Skippy plant. The facility produces 3.5 million pounds of peanut butter every week. It’s one of only two Skippy plants worldwide. The other one is in China.

Despite all that peanut butter production, aviation-related products are Little Rock’s chief export. The newest company to set up shop here is Arcturus Aerospace, which announced in April 2020 that it would be moving operations from California to the Arkansas state capital.

The northern part of the city features the Big Dam Bridge, the longest pedestrian/bicycle span in North America. It’s 4,226 feet long, spanning the Arkansas River. It connects to 14 miles of hiking and biking trails.

A system of paths known as the Arkansas River Trail follows the river from the downtown area to the bridge and beyond, totaling 88 miles through several communities. In Little Rock’s downtown area, it features a sculpture garden as well as the Medical Mile, which includes a 1,300-foot-long wall of murals focusing on healthy lifestyles such as smoking cessation and nutrition.

Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign put Little Rock at the center of politics that year, but the city first grabbed the national spotlight in 1957 when a segregation battle erupted at Little Rock Central High School.

This was the scene at Little Rock Central High School in 1957 when nine Black students started attending classes.

It ignited when nine Black students enrolled at the all-white school as a test of the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court Brown vs. Board of Education ruling that struck down the practice of “separate but equal” schools.

On the first day of class, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus ordered the state’s National Guard to block the Black students from entering. The students were turned away while a crowd of white supporters of segregation yelled at them.

During the next few weeks, President Dwight Eisenhower initiated legal proceedings against Faubus’ move. A federal judge eventually ordered the National Guard to leave and the city police took over security.

Another attempt to escort the teens into the school failed, so Eisenhower ordered federal troops to escort the Black students onto the campus.

Under the protective eye of 1,200 National Guard soldiers, the pupils were led past a jeering crowd of white protesters and began their first day of class on September 25. Federal troops remained at the school for the entire school year. The students were harassed and even physically assaulted throughout those months.

In September 1958, Faubus closed all Little Rock high schools pending a public election. Little Rock citizens then voted 19,470 to 7,561 against integration. So, Faubus kept the schools closed until September 1959.

Eight of the nine original students finished their high school careers via correspondence or at high schools elsewhere in the country. The other student, Ernest Green, graduated in May 1958.

Green eventually served as an assistant secretary in the Department of Labor under President Jimmy Carter. Another one of the students, Minnijean Brown-Trickey, worked as a deputy assistant secretary in the Department of Interior in the Clinton administration.

The Little Rock confrontation startled the nation and helped lead to integration of public schools nationwide.

The Little Rock Nine Foundation was established in 1999 to promote equality, justice and opportunity.

The nine students were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President Clinton in 1999.

Little Rock Central High School looks much the same today as it did in 1957

Little Rock Central High is still an educational facility as well as a national historic site. It’s the only operating high school in the United States with that designation.

During a visit to the campus in April 2023, we chatted with Valerie Hildebrand, a 5th grade teacher from South Carolina who was visiting Little Rock with her husband, Keith.

Hildebrand talks about the 1957 Central High standoff in her class and wanted to see the site for herself. She said her primary feeling while walking the steps of the high school was how terrified those nine Black students must have been.

She said it’s difficult for her students to believe this actually happened, but it’s an important event to include in classroom lessons.

“We have to know where we came from and try to not let it happen again,” Hildebrand said.

Her husband also noted that it’s important to remember the progress that has been made. The country has a long way to go on civil rights, he said, but there are no longer governors standing alongside troops telling children they can’t enter a school.

That theme is echoed in a park across the street where two remembrance arches with photos note that Central High is a success story because it became integrated, remained open and is now considered one of Arkansas’ premiere schools.

Eight years after those nine Black students were escorted to class, Little Rock Central High found itself at the center of another educational controversy.

In 1928, 63 percent of Arkansas voters approved a law that prohibited the teaching of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools. Efforts to repeal that law failed in the state Legislature in 1937, 1959 and 1965.

For the 1965-66 school year, new textbooks were introduced in Arkansas schools that included the subject of evolution. Susan Epperson, a biology teacher at Little Rock Central High, filed legal action to secure the right to teach evolution from those new textbooks.

The Arkansas Supreme Court ruled against Epperson, but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in her favor in 1968 in a 9-0 decision that stated that Arkansas’ law banning the teaching of evolution violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment that prohibits the government from favoring any one religion.

However, it wasn’t until 1981 that Arkansas legislators passed a law officially allowing the teaching of evolution in public classrooms. Creationists have attempted since then to overturn the law in the courts and in the legislature, but so far they have been unsuccessful.

Susan Epperson, now in her 80s, went to teach science at Pike’s Peak Community College and at the University of Colorado.

Little Rock is also the home of the William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum that honors the nation’s 42nd president.

One of the exhibits at the Bill Clinton presidential library in Little Rock, Arkansas

The exhibits there include a replica of the Oval Office as well as 2 million photographs, 78 million pages of documents, 20 million e-mails and 80,000 artifacts.

It’s also the home of the Clinton Foundation, a non-profit organization that is involved in global issues ranging from climate change to public health.

The 28-acre center cantilevers over the Arkansas River as a symbol of Clinton’s 1996 re-election campaign promise to “build a bridge to the 21st century.”

In one part of the center are panels from 1993 to 2000 that highlight what the Clinton administration did in each of those years of his presidency.

There are also exhibits that hone in on specific topics such as the economy and international efforts for peace.

During our visit in April 2023, there was a special exhibit on the efforts to secure the right to vote for women.

The Clinton center is a centerpiece of downtown Little Rock, which has developed over the past 20 years along the riverfront.

The River Market District is a revitalized retail area that features restaurants, shops, art galleries and music venues.

Three bridges in the district are now lit up at night by an array of colorful LED lights. The program is called River Lights in the Rock.

The Little Rock amphitheater along the Arkansas River with one of the city’s three lighted bridges behind it

One of the restaurants in the district is Gus’s World Famous Fried Chicken, an eatery my wife, Mary, and I discovered along with our friends Tom and Sue Keane during a 2014 trip to Memphis, Tennessee.

Gus’s was recommended by our hotel’s front desk clerk and we were glad he did. We sat a booth in western Memphis and ate what was probably the best fried chicken of our lives.

The restaurants got their start in the small town of Mason, Tennessee. It was there that Napoleon “Na” Vanderbilt and his wife, Ms. Maggie, began selling their spicy brand of chicken out of the back door of a tavern.

Encouraged by neighbors, the couple eventually built a restaurant on property they owned along Highway 70. Maggie’s Short Orders opened in 1973. The building is still there today.

After the couple died in the early 1980s, their son Vernon “Gus” Bonner inherited the restaurant and the recipe. In 1984, Gus and his wife, Gertrude, opened “Gus’s World Famous Fried Chicken” in Mason.

In 2001, Memphis resident Wendy McCrory brought a Gus’s chicken joint to her town. There are now 40 Gus’s chicken restaurants in 14 states.

Before we call it a day, we should note one other famous American from Little Rock.

General Douglas MacArthur was born in 1880 in the Little Rock Barracks, the third son of Captain Arthur MacArthur and Mary Pickney Hardy. He graduated first in his class at West Point in 1903 and was highly decorated as a soldier during World War One.

During World War Two, he was in charge of U.S. forces in the Pacific campaign against Japan. He achieved the status of five-star general and was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

The MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History in downtown Little Rock is named in his honor.

Tomorrow we will march forward as we head into Bayou country. Along the way we’ll visit the town where crop dusting and Delta Airlines were born as well as some places still recovering from back-to-back hurricanes in 2021.