Day 13: The Colorful Road to The Big Easy

April 1, 2021

Day 11: Spinach, Forts and Desegregation As We Enter the South

March 30, 2021Most recently updated on March 12, 2024

Partially driven on April 3, 2023

Originally posted on March 31, 2021

Our route today is a pretty straight north-to-south shot through the middle of Arkansas and Louisiana.

The best roadway out of Little Rock in n this direction is Interstate 530, a freeway that takes you through the rich agricultural region of the Arkansas River Basin. This 6.7 million acre watershed consists of 3.7 million acres of forest, 2 million acres of grassland, 430,000 acres of cropland and only 220,000 acres of urban use.

After 45 minutes along the rolling hills that surround I-530, you reach Pine Bluff, a city of 38,000 in southern Arkansas that is 77 percent Black and 18 percent white. And losing population quickly.

The town has a long history, beginning with its original inhabitants, the Quapaw tribe.

It was founded in 1686 by French colonists. By the late 1800s, it had developed into a cotton center and a major port along the Arkansas River.

In the early 1900s, Pine Bluff was hit by flood, drought and economic depression. It rebounded for a while during and after World War Two thanks to a munitions arsenal. However, as the 21st century dawned, the town was facing economic uncertainty and a crumbling infrastructure.

In 2014 and 2015, numerous buildings in the downtown area collapsed. In July 2015, part of Main Street was closed due to concerns other structures might falter. Many buildings today stand empty and are in need of repair. The city is eyeing one of those businesses for a major redevelopment. In February 2023, the City Council approved using $3 million in sales tax revenue to help build a Marriott Courtyard hotel to replace the now-shuttered Plaza Hotel. In March 2023, furniture and other items from the hotel started to be auctioned off to raise money to build new homes in the region. The $24 million, 125-room hotel is scheduled to open sometime in 2025.

Since 2000, the population in Pine Bluff has dropped from 55,000 to its current 38,000. In August 2021, the Census Bureau labeled Pine Bluff as the fastest shrinking city in the United States.

That declaration followed a 2020 report by 24/7 Wall St. that listed Pine Bluff’s metropolitan areas as having the highest rate of population loss in the country.

The report noted that Pine Bluff’s violent crime rate of 1,007 incidents per 100,000 individuals was significantly higher than the national average of 383 per 100,000. Crime appears to still be an issue. In spring 2021, it was reported that Pine Bluff had the highest robbery rate the previous year of any community in Arkansas. That year there were 29 homicides reported in Pine Bluff. In 2022, there were 20 homicides reported. It rose again in 2023, hitting 24 homicides by the end of October.

Pine Bluff currently has a median annual household income of $39,000 and a poverty rate of nearly 25 percent. The median home price is about $76,000,.

Pine Bluff’s economy today centers on cotton, soybeans, poultry, cattle, lumber and paper.

The International Paper Company mill, which opened in 1957, was sold along with other company assets in January 2020 to Carter Holt Harvey Limited. It’s still in operation as is another major paper mill purchased by Twin Rivers Paper Company in 2018.

One person of notoriety from Pine Bluff was Martha Mitchell, the wife of 1970s Attorney General John Mitchell. She was born here in 1918. Her father was a cotton broker and her mother was speech and drama teacher. Mitchell graduated from Pine Bluff High School in 1937. She eventually went to work in Washington, D.C., and married John Mitchell. During the Watergate scandal, Martha Mitchell publicly criticized President Richard Nixon and others for the 1972 burglary of the Democratic National Committee headquarters. The White House went to great lengths to try to silence her, but Mitchell kept talking until her death in 1976 from bone cancer.

Entering Louisiana

Interstate 530 ends in Pine Bluff, so we need to head south on Highway 530 to continue on this portion of our journey.

We eventually connect with Highway 11 east, which quickly leads us to merge onto Highway 425 south.

The drive through southern Arkansas is a scenic one. Thick rows of pine trees line both sides of the highway. There is significant distance between towns and a plethora of Baptist churches.

About an hour and a half after leaving Pine Bluff, we cross the border into Louisiana.

The landscape changes quickly after you zoom over the state line. The pine trees become less plentiful. They’re replaced by rice fields, swamp land and green pastures. The air becomes more humid, too.

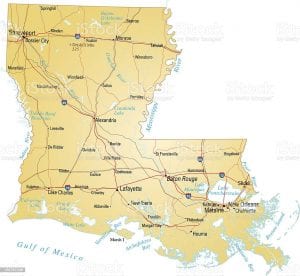

The Pelican State is 43,566 square miles, making the 33rd largest state. Its population of 4.5 million puts it at 26th. The populace here is 57 percent white and 32 percent Black, one of the highest percentages among states.

The state is a rich mixture of cultures from French to Spanish to Haitian to African. It also has more Native American tribes than any other Southern state.

Louisiana is the only state with parishes instead of counties. There’s 64 of them.

This is low-lying land, formed primarily by sediment that has flowed down the Mississippi River for thousands of years. That has created swamps and deltas that are perfect habitats for wading birds and all sorts of reptiles, insects and amphibians.

The mean elevation of Louisiana is only 100 feet with New Orleans sitting at 8 feet below sea level. The only other state with a locale that sits at negative sea level is California with Badwater in Death Valley clocking in at 282 feet below.

Louisiana also ranks low when it comes to economics and health.

A 2022 report ranked Louisiana as being the least healthiest of all the states, even lower than Mississippi, which has traditionally held the bottom spot.

Louisiana’s median annual household income is listed as $57,000, among the lower echelons of the states, with a poverty rate of more than 18 percent.

This is true in much of the South. The authors of a 2020 report stated that this region has struggled economically because it has long been reliant on an agriculture industry that hasn’t advanced with the times. Neither have the textile and manufacturing businesses, which have been overrun by foreign industries that do the jobs more cheaply.

Louisiana does have its economic strengths.

It is the second among states in seafood production, behind only Alaska. It supplies the United States with 90 percent of its crawfish and is the leading state in shrimp production. The state’s number one crop is sugar cane followed by cotton and soybeans. Its top manufacturing industry is chemical production followed by petroleum products. It has one of the highest petrochemical concentrations in the country.

In late October 2021, sports gambling became legal in public land casinos in Louisiana. Four casinos initially began taking sports bets the final week of that month. In January 2022, online sports betting got the approval ahead of the National Football League playoffs. The state generated about $32 million in sports betting revenue in 2022. That went up significantly in 2023 with a record more than $300 million in revenue recorded.

In 2019, Louisiana became the first state in the Deep South to legalize medical marijuana. The industry seems to be thriving. In February 2023, Good Day Farm, the largest medical marijuana producer in the state, announced it is doubling the production capacity at its complex in Ruston to meet the growing demand.

Coca Cola and Delta Air Lines

An hour after crossing the Louisiana border we arrive in Monroe.

The town has a population of 46,000 people, making it ninth most populous city in Louisiana. It is more than 60 percent Black and 33 percent white. Its median annual household income is listed as $36,000 with a poverty rate of 35 percent.

Ironically, we’re stopping here due to two historic business successes that have roots in Monroe.

The town was founded in 1785 by French pioneers from southern Louisiana. It was named after a steamship that bore the name of President James Monroe that was the first such vessel to reach this settlement by river.

Monroe’s first historic industrial achievement came when Joseph Biedenharn and his family moved to town in 1913.

Biedenharn was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1866. As a teen, he worked in his father’s candy store. That shop had a soda fountain where beginning in 1890 Biedenharn mixed syrup and carbonated soda to make Coca Cola, a soft drink that had been invented a few years earlier by a pharmacist in Atlanta.

Biedenharn sold the new drink for 5 cents a glass. The drink proved popular, so in 1894 Bidenharn hit upon the of actually bottling the soda rather than just selling it from the tap. He set up a bottling operation inside the store and began shipping cases all over the South.

The Biedenharn Museum and Gardens in Monroe, Louisiana

In 1913, Biedenharn purchased a small bottling factory in Monroe and began mass producing Coca Cola there. It was the first full-scaling bottling operation for Coca Cola in the country.

The Biedenharn Museum and Gardens in Monroe has displays of soda fountains, Coca Cola signs, a delivery truck and other memorabilia.

However, the soft drink wasn’t the only fledging industry Biedenharn was involved in.

In 1925, he and other entrepreneurs purchased Huff Daland Dusters. That company had been officially formed a few months earlier in Macon, Georgia, where pilots had been putting on exhibitions with special planes that could spray chemicals onto farm fields to kill insects but not harm plants.

They called it crop dusting because they used dry chemicals that looked like dust when they were dropped from the planes. The planes were first used in the South in the 1920s to eradicate agricultural pests, in particular the boll weevil that could devastate an entire field of cotton.

Huff Daland Dusters was the first commercial enterprise for this new industry. When Huff arrived in Monroe, the company brought with it 18 specialty planes, the largest privately owned aircraft fleet in the world at the time. That fleet soon grew to 25 planes.

In 1928, C.E. Woolman, the chief entomologist for Huff, negotiated a contract with Peru to deliver airmail. The company quickly expanded to passenger and mail service.

Later that year, other investors joined the company and it was renamed Delta Air Service for the Mississippi Delta region it primarily served.

In 1929, Delta began offering passenger flights from Louisiana to Texas and Mississippi. Over the years, its business expanded greatly and Woolman was eventually named chief executive officer.

In 1941, Delta moved its headquarters from Monroe to Atlanta. In 1945, the company name was changed to Delta Air Lines, which is now the second largest airline in the world, behind only American Airlines.

The history of Delta Air in Monroe is on display at the Chennault Aviation and Military Museum. The 10,000-square-foot facility opened in 2000 and contains 11,000 artifacts.

This Delta exhibit is not the only local history recorded at the museum.

The complex also shines a spotlight on Selman Field, the airport where Huff and Delta first operated.

During World War Two, Selman Field was the country’s only complete navigation training facility for the Army Air Corps. More than 15,000 navigators who flew missions during the war trained here.

The field was converted back to civilian use in 1946 and is now the Monroe Regional Airport.

The museum also pays tribute to its namesake, General Claire Lee Chennault, who spent his final years in Monroe.

Chennault, a native of Texas who grew up in rural Louisiana, fought in World War One and earned his wings as a pilot for the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1919. Chennault found a career training pilots until history would come knocking in 1937.

Chinese military officials asked Chennault to take command of its fledging air force in its war with Japan. Chennault is credited with leading China’s pilots to significant victories over the superior Japanese air force. He was promoted to brigadier general in the Chinese military in 1941.

Part of his duties was to oversee a group of volunteer pilots from the United States who became known as the Flying Tigers.

The volunteer pilots fought aerial battles with Japanese aviators over China and Burma. They played a key role in keeping China’s ports open as well as securing the Burma Road for supply trucks.

In 1942, the Tigers became part of the United States’ 10th Air Force, which became a major component of China’s air war with Japan. Chennault remained in command. He was promoted to U.S. brigadier general in 1942 and major general in 1943.

In July 1958, Chennault was given an honorary title of lieutenant general. He died nine days after receiving that honor.

There are a couple other well-known people who hail from Monroe.

One is Bill Russell, the Hall of Fame basketball player who helped lead the Boston Celtics to 11 championship in 13 seasons in the 1950s and 1960s. Russell was born in Monroe in 1934.

The other is Huey Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party. Newton was born in Monroe in 1942.

The Eye of the Hurricanes

Highway 165 south is still the road of choice as this route departs from Monroe.

There’s more than 3 hours of driving through Louisiana bayou country before we hit today’s final destination.

Just a few miles south of Monroe, we drive past a landmark that is important in the prehistoric history of the Pelican State.

Native tribes first arrived in the Louisiana area more than 13,000 years ago. They found the low lands, rivers and estuaries conducive to hunting and fishing.

The Watson Brake Mounds in central Louisiana

Just west of Highway 165 is a site known as the Watson Brake Mounds. It consists of 11 dirt mounds connected by ridges that surround what appears to be an ancient plaza. Nine of the mounds are between 2 feet and 11 feet high. The largest mound stands 25 feet. They cover an area that measures 984 feet by 646 feet.

It’s believed the mounds were constructed over a 700-year period between 3500 BC and 2800 BC. They are believed to be among the oldest large-scale mound sites in North and South America.

Watson Brake was built by tribes who were part of what is known as the Evans Culture. These prehistoric people appear to have chosen this site because it had access to lowland as well as upland locations.

Archaeologists say this culture lived in Louisiana when sea levels were high, so river flows were slow. They hunted using notched spear tips and were among the first to use clay cooking vessels. They were also the first to be build mounds.

There are 13 prehistoric mounds spread around Louisiana. Archaeologists aren’t sure why the mounds were built. They aren’t burial grounds, although they do appear to have been inhabited for extended periods of the year.

No known mounds were built between 2800 and 1800 BC, although construction resumed after that 1,000-year hiatus. It’s unknown why the building stopped, although it may have been due to severe flooding during those centuries.

Highway 165 continues its southward trek, cutting through one small town after another. In the middle of this portion of the route, you zoom through Alexandria, a town of 42,000 people along the Red River known for its saw mills.

The parade of small towns continues until Highway 165 ends at Interstate 10, our traveling companion from our first day in Texas.

You only have to venture a few miles west on I-10 to reach Lake Charles, the final stop on this leg of the journey.

Lake Charles sits in the southwest corner of Louisiana, about 40 miles north of the Gulf of Mexico and 30 miles east of the Texas border.

It also sits right in the path of hurricanes that churn through the Gulf of Mexico. That includes two major storms that devastated the Louisiana coastline in 2020.

Lake Charles has 82,000 residents, making it the sixth most populous city in Louisiana.

It’s also one of the most humid places in the United States with an average humidity of 90 percent in the morning and 72 percent in the afternoon.

In the 1700s, this area was a popular port for pirates. Among them was Jean Laffite, the infamous smuggler who temporarily redeemed himself by helping the United States defeat the British in the Louisiana area during the War of 1812.

The city was founded in 1861 by a merchant who had established a trading post. A busy lumber mill and a schooner port helped the city grow. Its chief exports were wood products made from timber in the pine and cypress forests north of town.

The arrival of the railroads in the 1880s elevated that industry as well as lured grain farmers who came from the Midwest and turned the region into one of the major rice-growing areas in the United States.

After World War Two, Lake Charles developed into one of the nation’s primary petrochemical industry centers. It’s also home to the Trunkline LNG Terminal, one of the few liquified natural gas terminals in the United States.

In 2019, a new $3 billion petrochemical complex joined the array of industrial facilities. The Lake Charles Complex has an ethane cracker that’s used to manufacture caustic soda, chlorine and other products. There’s also a monoethylene glycol plant that produces a key component used to make paper, textile fibers, latex paints and other products.

Manufacturing facilities include The Shaw Group that exports parts for nuclear power plants. Other industries include aerospace, agribusiness, healthcare and maritime operations. All these facilities use the Calcasieu Ship Channel to transport their wares around the world.

Just outside of the eastern city limits is Louisiana Spirits, a distillery founded in 2011 by two brothers from the Lake Charles area and an investor from Baton Rouge. Their 18,000-square-foot facility sits on 22 acres in Lacassine. Their signature product is Bayou Rum, whose chief ingredient is sugar cane from nearby fields.

Lake Charles is also Louisiana’s gambling mecca with four major casinos, including the 18-story Golden Nugget with its 1,904 hotel rooms and L’Auberge Casino Resort with its 1,000 guest rooms.

Alligators are a common site here as well as throughout southwestern Louisiana. There are signs around town with warnings not to get to close or to try to feed the reptiles.

The city is also known for its festivals. There are 75 of them held during a typical year. There’s the Louisiana Pirate Festival, a 12-day event usually held in early May. The city also has its own Mardi Gras celebration, usually held in January and February.

Some of the damage from the 2020 hurricanes in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Photo by Yahoo News.

In recent years, Lake Charles has also had to deal with the destruction leveled by hurricanes.

The city was clobbered in September 2005 by Hurricane Rita, a category 5 storm whose winds reached 180 miles per hour while it spun through the Gulf of Mexico. To date, it’s still the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the gulf.

Rita came ashore as a category 3 storm with winds of 115 miles per hour. It was the most powerful hurricane to hit the southwest coast of Louisiana since Hurricane Audrey in 1957. Seven people died in the 2005 natural disaster, including one person in the Lake Charles area.

Rita’s storm surge flooded downtown Lake Charles, destroyed a dockside casino and badly damaged the lakefront civic center. The regional airport was seriously damaged and had to be rebuilt. Harrah’s Hotel & Casino was destroyed and wasn’t rebuilt. Its casino license went to the Golden Nugget, which opened in 2014.

The damage from Hurricane Rita was a overshadowed that year due to the devastation and death caused in New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina, which had struck the month before. Some folks displaced by Katrina were staying in hotels in Lake Charles when Rita roared through.

In 2020, Lake Charles received a double whammy when Hurricane Laura came ashore in late August and then was followed by Hurricane Delta in early October.

Hurricane Laura hit the Gulf Coast as a category 4 storm with winds reaching 150 miles per hour. It didn’t slow down much as it plowed inland. The Lake Charles Regional Airport reported gusts of 128 miles per hour.

The storm knocked out power and water service in Lake Charles for days. In the weeks following, blue tarps could be seen on most homes where at least sections of roof had been torn away.

The city’s downtown was also hard hit with windows being blown out of office buildings. A fire broke out at a chemical plant, prompting a shelter-in-place order.

Officials at the Port of Lake Charles reported extensive damage. Transit sheds, ship loaders and warehouses were among the casualties. A number of docked vessels sunk. Port officials used emergency funds to purchase a $6 million crane to help with the loading and unloading of cargo.

The blue tarps were still on roofs when Hurricane Delta barreled through a little more than a month later as a category 2 storm with winds up to 100 miles per hour.

Although the winds were less powerful than Laura, there was more serious flooding from Delta as 15 inches of rain fell in a two-day period. This produced serious damage in homes that had already been crippled by Laura.

in mid-May 2021, nature struck again. Lake Charles was one of cities to get deluged by a powerful storm that put 30 million people in Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas in danger of flooding. The southern portion of Lake Charles received more than 12 inches of rain in a 12-hour period. The mayor said hundreds of homes had been flooded in what may well turn out to be a 100-year event. At least 80 Lake Charles residents had to be rescued from the rising waters.

In August 2021, Lake Charles caught a break when it suffered relatively little damage as Hurricane Ida roared ashore east of the city. In fact, some people from other parts of Louisiana actually took shelter in Lake Charles.

Despite all the storms, there are plans for a massive solar energy facility on 3,400 acres of land just outside of town. Officials at Aurora Solar have proposed an electricity generating plant on a former rice field that would utilize 1 million solar panels. However, some local residents have filed a lawsuit, saying they haven’t received sufficient guarantees on health, safety and environmental issues.

We’ll enjoy the sunshine and the flavor of Lake Charles as we park for the night.

Tomorrow, it’s Cajun culture and our first glimpse of the Mississippi River as we ease our way to The Big Easy.