Day 21: Following My Grandfather’s Footsteps Into Kentucky

April 9, 2021

Day 19: War, Religion and Remembrance in Virginia

April 7, 2021Most recently updated on March 20, 2024

Originally posted on April 8, 2021

Day 20 begins by simply crossing State Street in downtown Bristol.

That’s where we travel on our journey from Virginia into Tennessee.

This particular state is shaped like a sawtooth rectangle that is nearly four times as long as it is wide.

Tennessee measures 112 miles north to south, but it stretches 432 miles from the Mississippi River on its western edge to the Appalachian Mountains in the east.

Despite its length, Tennessee is only the 36th largest state at 42,000 square miles.

Nonetheless, Tennessee has more than 7 million residents, making it the 15th most populous state. Of that population, 73 percent are white and nearly 17 percent are Black.

The first inhabitants of what is now Tennessee are believed to be people from Asia who crossed into North America during an ice age more than 20,000 years ago. A series of native tribes who specialized in hunting lived in the region in the centuries that followed.

The Spanish were the first colonial power to explore the area, doing so in 1540. The British came through in 1756.

The origins of the state began with the Watauga Association, a group of about 70 landowners that formed a frontier government outside of British rule in 1772. The association negotiated a 10-year treaty with the Cherokee. The government lasted less than five years due to the American Revolution, but it set the stage for Tennessee statehood.

The region was initially part of North Carolina and then the Southwest Territory becoming the 16th state, admitted to the Union in 1796.

Tennessee achieved its nickname of the “Volunteer State” because of the thousands of state residents who volunteered to fight against the British in the War of 1812.

The initial pioneers enjoyed good relations with the Cherokee. The word “Tennessee” derives from the Cherokee village known as Tanasi.

However, as European settlers took over more and more land, conflicts arose that eventually led to the native tribes being removed.

In 1838, more than 12,000 Cherokee tribe members were forced to walk from Tennessee and other states to Oklahoma in a forced relocation program known as the “Trail of Tears.” Thousands of those Native Americans died while making the trek.

Tennessee was the last Southern state to secede at the start of the Civil War and was the first one readmitted after the war ended. There were definitely split loyalties over that conflict. Tennessee supplied the second most soldiers to the Confederate cause, behind only Virginia. However, it also supplied more soldiers to the Union side than all the other Southern states combined.

Farming was the main economic activity in the 1800s. Pioneers ground corn and wheat to make flour and meal as well as spun cloth, processed hides and manufactured farm equipment and furniture.

In the 1800s, manufacturing industries began to emerge. Many revolved around iron and lead, producing products such as nails and furnaces. Later in the century, textiles and furniture were among the items manufactured.

In the 1900s, the state shifted to a more diverse economy. There were two big projects that helped drive that change. We will discuss both of them at different locations during our travels today.

Farmland still covers 44 percent of the state. The 82,000 farms here produce soybeans, greenhouse products and cotton as well as broiler chickens. The largest agricultural commodity is beef cattle.

Manufacturing ranges from processed foods, whiskey and other beverages as well as transportation equipment and chemicals.

Tourism is also a $20 million industry in Tennessee. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most visited national park in the country. There’s also Memphis, along Tennessee’s Mississippi border, that brings in visitors with Elvis Presley’s Graceland home and other attractions. Finally, there is Nashville, the center of country music.

———————————————

Before we travel some of Tennessee’s vast length, we need to quickly visit the “other Bristol.”

As mentioned during our Day 19 virtual sojourn yesterday, the Tennessee Bristol is larger in size and population than its Virginia sibling.

The main reason for popping in today is the Bristol Motor Speedway. The race track opened in 1961 with 17-year-old Brenda Lee singing the national anthem.

The speedway is known as “The Last Great Colosseum” because it is surrounded by grandstands on all sides. It contains a .53-mile concrete oval track, which has been called the “World’s Fastest Half Mile.”

The track is where NASCAR’s Food City 500 is held in the spring. Other racing events are scheduled through most of the year.

The Bristol speedway has a seating capacity of 160,000. The races there attract the largest crowds of any sporting events in Tennessee.

Before we leave Bristol, we want to mention one of the city’s more famous hometown residents.

Ernest Jennings Ford was born here in 1919. He was better known as Tennessee Ernie Ford. The singer had a string of hits in the 1950s and 1960s such as “Sixteen Tons.” Ford, who died in 1991, is in the Country Music Hall of Fame.

———————————————–

We hop onto Interstate 81 and head west but only for a short distance.

Just 10 miles down the freeway from Bristol is the community of Blountville.

This village of 3,100 people in northeastern Tennessee is officially not a town nor a city. It’s a census dedicated area. Yet, it is still the seat of Sullivan County.

It gained this status in 1792 when settler James Brigham donated 30 of his 600 acres to set up a center of county government.

The main reason for stopping in on this day is that Blountville is the home of Northeast State Community College, a school of 5,400 students that was founded in 1966. The college offers degrees in 30 areas of study, in particular technical education. It also has an active transfer programs in which its students can vault more easily to a four-year school.

Northeast State participates in two programs that are worthy of discussion here.

Northeast State Community College in Blountville is involved in two statewide programs designed to encourage Tennessee residents to attend college. Photo by Unigo.

The first is the Tennessee Promise project, which provides free two-year scholarships to those who attend community colleges or technical schools.

The goal of the program is to provide financial support and mentoring services to high school seniors in an effort to increase the number of students who attend college in Tennessee.

Students can use the scholarship at any of Tennessee’s 13 community colleges or 27 colleges of applied technology. The students must meet regularly with a mentor, put in at least 8 hours of community service per term and maintain a grade point average of at least 2.0.

Tennessee Promise was established in 2014 as a way to help lower income students as tuition and others costs continue to rise. Since then, at least 30 other states have adopted similar programs.

So far, the program appears to be having some success. A 2022 report noted that there were 88,000 students enrolled at Tennessee’s 13 community colleges, more than half of the state’s 140,000 students in public higher education facilities.

The second program is Tennessee Reconnect, which provides the same two-year scholarships for adults who want to return to college or attend for the first time. There are also provisions for veterans and active members of the military.

The Reconnect project began in 2018. The purpose is to create highly skilled workers for the jobs of the future. It’s estimated that more than half the jobs in Tennessee in 2025 will require a college degree or certificate.

The “Drive to 55” organization is working with Tennessee Reconnect to reach a goal of having 55 percent of the state’s workforce equipped with a college degree or certificate by 2025.

The programs are part of efforts to make college more accessible nationwide.

A report by the National Center for Education Statistics notes that undergraduate enrollment at post-secondary institutions that grant degrees dropped by 8 percent between 2010 and 2018. In May 2022, it was reported that college enrollment nationwide had dipped another 5 percent, although that decline had slowed to 1 percent by fall 2022 and 2023 fall enrollment actually rose by 2 percent. Projections indicate that enrollment won’t increase by much the rest of decade. In fact, a June 2023 report stated that nationwide college enrollment may have peaked at 18 million more than a decade ago.

A report by the Center for American Progress recommends a stronger effort to establish debt-free college education and an increase in Pell grants. It also urges college administrators to adjust their programs and their way of thinking to address these issues.

The center reports that college educations are becoming more important as our nation shifts to a more technology-based economy. Experts say college-educated workers not only obtain better paying jobs, they also tend to be more engaged in their communities.

Another component is the debt that college graduates face when they leave school and enter the job market. The total of student debt nationwide has topped $1.7 trillion, although that figure actually dipped slightly in 2023 for the first time ever. More than 43 million people have student loan debt in the United States with the average debt being near $40,000.

A report by Scholarship America concluded that student debt forces many college graduates to accept lower paying jobs so they can meet their financial obligations more quickly. These debt-burdened young adults are also 36 percent less likely to buy a house, a factor that can produce a drag on the overall economy.

President Joe Biden promised to ease the burden of student loans. However, in July 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court blocked Biden’s plan to cancel $430 billion in student loan debts. Nonetheless, the president has used executive actions to cancel $160 billion in federal student loan debt for more than 4.5 million borrowers since he took office.

Electrical Energy and Atomic Power

It’s back on Interstate 81 in a southwesterly direction as we head more toward the middle of Tennessee.

The freeway comes to an end when we merge onto Interstate 40, our traveling companion from the first three days of our journey.

An hour and a half down the road from Blountville, you hit the town of Knoxville.

The community of 200,000 people is the third most populous city in Tennessee, behind Nashville and Memphis and just ahead of Chattanooga.

It’s also the home of one of the best-known federal projects from the Great Depression.

In addition, it’s the birthplace of a popular soft drink whose marketing campaign includes hillbilly moonshiners. We’ll explain in a bit.

First, some history.

This spot where the French Broad River meets with the Holston River to form the Tennessee River was initially inhabited by Native American tribes about 1000 B.C. The Cherokee were here when European explorers arrived in the 1700s.

The town was established in 1786 when settler James White built a fort and a cluster of cabins. The village was named after Secretary of War Henry Knox.

The 1791 Treaty of Holston settled peace terms with the local tribes and allowed the town to develop.

Initially, Knoxville was a stop for travelers. After the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad arrived in 1855, the city became a wholesale and manufacturing center. Between 1880 and 1887, there were 97 new factories in operation, producing textiles, food items and iron products. Between 1895 and 1904, more than 5,000 new homes were built.

The rapid industrialization brought with it problems such as air pollution, unsafe drinking water and strained race relations.

Manufacturing started to wane as the Great Depression unfolded and that’s when President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs stepped in.

In 1933, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was established to provide people with jobs and boost the economy of this mountainous region as well as parts of six surrounding states.

Its projects mostly involved flood control and electricity generation. The program also provided malaria control, forest fire prevention, erosion control and fertilizer development. The power generation reduced rates and encouraged consumers to buy electrical appliances.

Tennessee Valley Authority dams provide electricity for 10 million people in 7 states. Photo by Britanncia.

By 1934, more than 9,000 people were working for the TVA. Between 1933 and 1944, the agency built 16 hydroelectric dams in the Tennessee Valley. Those dams displaced thousands of residents who had to move when their lands were flooded to create reservoirs.

The owners of privately held utilities fought against the TVA, viewing the cheaper energy the agency produces as a threat to their business. They took their case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where they lost in 1939 when the justices upheld the constitutionality of the law that created the TVA.

Today, the Tennessee Valley Authority is still headquartered in Knoxville.

The public corporation contracts with municipalities and cooperatives to supply wholesale power that is sold in bulk. About half of that electricity goes to federal agencies.

The TVA provides power to 10 million residents in seven Southeastern states. That electricity is generated by 29 hydroelectrical plants, nine natural gas plants, five fossil fuel plants and three nuclear plants and 14 solar energy units that are sourced out to developers.

The TVA remains the largest public utility in the United States.

Officials at the TVA say the mission of their agency hasn’t changed much since it was created more than 90 years ago.

Patricia Ezzell, a TVA historian and senior program manager, told 60 Days USA in 2021 that when the TVA was created the people in the region had an annual income about 45 percent below the national average. In addition, the literacy rate was low, malaria was common and malnutrition was rampant.

“We were created to transform a region,” Ezzell said.

She said the TVA “serves the people of the Tennessee Valley to make life better” through economics, environmental stewardship and electricity.

Ezzell notes one of the first accomplishments of the TVA was controlling the floods that used to plague the region. They did this in part by building 49 dams along the Tennessee River. The projects have avoided an estimated $9 billion in flood damage in this area since 1933. They’ve also made the 652 miles of the Tennessee River more navigable.

“Flood control is one of those foundational missions that is as important today as it was in 1933,” said Scott Fiedler, a TVA media relations spokesperson.

Controlling floods has allowed the economy in the region to flourish, too.

The TVA currently employs 10,000 people itself and the agency estimates it helps create 67,000 jobs across the region.

The TVA is probably best known for its affordable and reliable electricity.

Fiedler said they are able to do this because they are a public entity that doesn’t have to turn a profit.

“The public power model gives us an advantage over the investor-owned utilities,” he told 60 Days USA in 2021. “We are not beholden to shareholders.”

Fiedler said TVA’s electricity has had a more than 99 percent reliability rate over the past 20 years. This consistency was duly noted during February 2021 when winter storms knocked out power in neighboring regions as well as when frigid temperatures hit the state in January 2024.

“The way we run our system through a diverse generating portfolio ensures that we have electricity available every time you turn on the light switch,” he said.

The TVA’s electricity production was one reason the 1982 World’s Fair was held in Knoxville. The theme of that event was “Energy Turns the World.”

President Ronald Reagan officially opened the fair, which ran from May 1 to October 22. The 67-acre site was visited by 11 million people.

The city sold $46 million in bonds to pay for the fair. It paid off the debt in 2007, two years ahead of schedule.

The impetus for the fair was to create an area that could be used for downtown redevelopment. It didn’t quite work out. No major projects occurred after the fair and most of the buildings were torn down. Much of the site is now a park.

The only things left from that 1982 event are a restaurant, a 216-foot Rubik’s Cube, an amphitheater and the Sunsphere. The tower’s observation deck was opened to the public in 2004. The Sunsphere was part of a 1996 episode of The Simpsons where Bart Simpson and some friends take a spring break trip to Knoxville and knock it over.

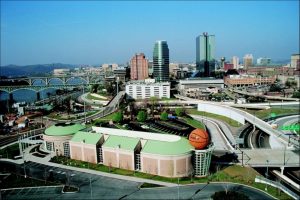

The Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Tennessee. Photo by Downtown Knoxville.

Knoxville is also home to the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame. The 35,000-square-foot facility opened in 1999 and honors women basketball players at all levels. There are now nearly 200 inductees, some of them men who have contributed to the development of women’s basketball. There are three basketball courts where visitors can test their skills. On top of the center is the world’s largest basketball at 30 feet high and with a weight of 10 tons.

Finally, Knoxville is the place where Mountain Dew was invented.

The story starts with two brothers, Barney and Ally Hartman, who operated an Orange Crush bottling facility near Augusta, Georgia, shortly after World War One.

When their Orange Crush factory went bankrupt in 1932, they moved to Knoxville. They sold beer and Pepsi after Prohibition ended in 1933. Soon after, they formed the Hartman Beverage Company.

In the 1940s, they decided to develop a lemon-lime flavored soft drink to use as a mixer with their Old Taylor Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey. They asked a Virginia master flavor mixer to come up with a concoction.

The mixer came up with Mountain Dew and the brothers debuted it at a 1946 bottling convention. The green bottles featured a hillbilly with a rifle in one hand and a jug of moonshine liquor in the other.

The public, however, thought the Hartmans’ product was kind of blah. In 1954, the brothers awarded a Mountain Dew franchise to Tri-City Beverage in nearby Johnson City. In 1960, that company developed a new taste for the high-sugar, high-caffeine beverage. Sales of that new Mountain Dew took off.

The soft drink brand was purchased by Pepsi in 1964.

Today, Mountain Dew, which is popular with skateboarders, race car drivers and others, is the fifth most popular soft drink in the United States behind Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, Diet Coke and Dr Pepper.

And it all started in Knoxville.

———————————————

It’s just a half-hour drive west from Knoxville to reach a town with the nickname “The Secret City.”

Oak Ridge was one of the three places selected by the U.S. military for the Manhattan Project scientists who were developing the atomic bomb during World War Two.

The other two spots were the Los Alamos area in New Mexico that we visited on Day 4 and the community of Hanford in eastern Washington.

Oak Ridge was the site where scientists worked on separating the isotope uranium 235. That product was shipped to Los Alamos, where the atomic bomb was assembled.

The Tennessee community was chosen for this dangerous work because of its isolation inside a 17-mile-long area of ridges and valleys. It also had access by road, the Clinch River and a railroad as well as the Norris Dam, one of the first major TVA projects, that could provide electricity and water.

Ray Smith, Oak Ridge’s historian, told 60 Days USA in 2021 there was another major factor.

President Franklin Roosevelt had contacted Tennessee Senator Kenneth McKellar about this project and the need to keep it secret. McKellar made sure his state got one of the locations.

“That probably had more to do than anything with Tennessee getting the project,” Smith said.

In 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began acquiring 60,000 acres in what would become Oak Ridge. Eviction notices were sent to 3,000 residents of the surrounding communities, giving them just a few weeks to move. The citizens weren’t told why they had to vacate the area other than it was needed for military purposes. After they left, construction began on three major facilities as well as the city.

Smith said many of the residents first heard of the relocation from the high school principal. Many of the folks didn’t have cars and others who had cars couldn’t buy gasoline or tires as those items were rationed. However, they left anyway, some within a matter of days.

“What they did have,” Smith said, “was young men in the military getting killed. They wanted to do anything they could to stop the killing and end the war.”

The Army built a completely new town for the Manhattan Project workers. About 3,000 prefabricated homes were quickly put together. At one point, 30 to 40 houses were being completed every day. There was also 300 miles of roads, 55 miles of railroad tracks, 17 restaurants, 13 supermarkets, 10 schools and seven movie theaters that were built.

Oak Ridge grew from 3,000 people in 1942 to 75,000 residents in 1945. Eventually, 80,000 people were employed at the secret facility.

Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was known as “The Secret City” because of its work on the atomic bomb during World War Two. Photo by The Oak Ridger.

Three main sites were established, each doing its part to help separate out uranium 235.

The first was a complex known as Y-12 that employed electromagnetic separation. About 22,000 people worked here.

The second site was K-25, which housed a gaseous diffusion process. This facility consisted of 50 four-story buildings in a U shape on 1,500 acres. At the time, it was the largest building in the world under one roof.

The third site was S-50. It consisted of 2,142 columns, each more than 40 feet high. They housed thermal diffusion separation processes.

In 1945, all three separation systems were combined to provide the maximum concentration of material needed to construct the first atomic bomb named “Little Boy” that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1945.

There was also an X-10 site that included a graphite reactor to prove that a uranium reactor could produce plutonium. Hanford, Washington, was then chosen as the site to build three larger reactors to produce the plutonium was used to build “Fat Man,” the bomb that was dropped days after “Little Boy” on Nagasaki, Japan, and brought an end to World War Two.

“Little Boy” was an uranium-based weapon while “Fat Man” was plutonium based.

The Oak Ridge project was top secret. The town was not listed on any maps. There were guards posted at the town’s entrances and residents were required to wear badges any time they were outside their homes.

Signs around town warned residents not to discuss their work. Smith said some people in town were told to carry 3-by-5 index cards in their pocket and take notes on anybody they heard discussing the project. Those cards were then mailed off. Later, the residents learned that about half the town was involved in the secret note taking.

“They were spying on each other,” Smith said.

Most employees were only aware of their small part of the project. Many didn’t know they were working on an atomic bomb until the first one was dropped on Japan.

Oak Ridge was a segregated town with separate housing and schools for its Black employees and their families. Smith said Black residents did most of the lower level labor jobs and had to live in huts that were separated in groups between men and women with restrictions on visitations.

The schools weren’t integrated until 1955 after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling. Smith noted that the high school and junior high school in Oak Ridge were the first public school in the South to integrate. The town had a 65th anniversary celebration in September 2020 for the 85 Black students who attended the white school in Oak Ridge in 1955.

Smith is a treasure trove of Oak Ridge knowledge. You can learn more historical facts about the town on his website at draysmith.com.

In 1947, Oak Ridge was transferred to civilian control under the authority of the Atomic Energy Commission.

The S-50 site was dismantled soon after the war.

The K-25 site enriched uranium until 1985. It was demolished in 2015. Smith notes that the enriched uranium program ended there in 1964. However, the uranium it produced is still in use in weapons, submarines and some reactors. The material is stored at the Y-12 site.

“Oak Ridge was a significant contributor to the Manhattan Project. Since, it has been a significant contributor to global security,” Smith said.

The Y-12 site helped produced thermonuclear weapons after the war. It now helps manufacture and store materials deemed vital to national security.

The Oak Ridge National Laboratory operates under the Department of Energy and employs more than 5,000 people. In 2018, officials at the lab announced they had created the world’s fastest supercomputer. Smith said the lab’s supercomputer has since lost that title, but a new supercomputer was coming within the next few months to reclaim the crown. Indeed, in May 2022, the Frontier supercomputer at Oak Ridge was hailed as the world’s fastest and the first one to break the coveted exascale barrier.

The national lab also houses the Spallation Neutron Source, a facility that in the most basic sense produces neutrons. The advancements here have been used to improve products ranging from mobile phones to batteries to bridge cables.

Since the 1980s, there have been peaceful anti-nuclear protests at the sites.

The American Museum of Science and Energy in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Photo by Wikipedia.

The town now has 33,000 people, about 80 percent of whom are white. The median household income is a $67,000 a year. The economy revolves around the science and research centers.

There are five museum complexes in town that highlight the field of science as well as the history of what went on in Oak Ridge during World War Two.

The American Museum of Science and Energy was established in 1949. Its mission is to teach children about energy, in particular nuclear power. The museum does have exhibits from the atomic bomb research, but its focus is more on more current science.

The K-25 History Center opened in February 2020 and has exhibits explaining the history of the gaseous diffusion process.

The Y-12 History Center spotlights the work that happened in this facility during World War Two as well as the Cold War and Y-12’s current mission.

The Oak Ridge History Museum opened in 2019. Its mission is to educate the public about the daily lives of the people who lived here during World War Two.

And the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge is the location of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park visitor center as well as a collection the photographs of Ed Westcott, the photographer who made all the black and white photos of Oak Ridge during the Manhattan Project.

Another science-based company has moved into town. General Fusion, a Canadian-based company that produces carbon-free fusion energy, announced in November 2021 that it had chosen Oak Ridge as its U.S. headquarters as well as its first operation in the United States.

Smith said Oak Ridge is now slowing changing as more service workers move into town. However, the town still retains many of the scientific facilities and cultural amenities that have been there since the Secret City was built.

“Oak Ridge is a small town, but it’s large city atmosphere,” he said.

Even with the changes, Smith said the people of Oak Ridge are still proud of their city’s heritage.

“People here are aware of the history and are proud of the history,” he said.

———————————

From Oak Ridge, we jump back on Interstate 40.

It’s a drive of 2 ½ hours to reach our final destination today.

As we head west, we cross back over into the Central Time Zone and pass through a mountainous region known as the Upper Cumberland.

This 5,000-square-mile area in north-central Tennessee consists of 14 rural counties situated between Knoxville and Nashville.

There’s a lot of open space in the Upper Cumberland, including 16 state parks and the 125,000-acre Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area. The region is known for its natural beauty that includes 12 waterfalls.

About 360,000 people live in 30 small towns, most of them with populations under 30,000. Many of the residents here are 3rd and 4th generation descendants of early settlers and still live close to the land.

The most populous city is Cookeville, a community of 37,000 that sits along Interstate 40 that likes to call itself the “Hub of the Upper Cumberland.”

The town was settled in 1812 by Richard Fielding Cooke, a land owner who later became a state senator and was influential in Cookeville being named as the seat of Putnam County.

The early economy here was dominated by agricultural, timber and mining.

Today, manufacturing is the economic catalyst. The town also enjoys some tourist trade thanks to the outdoor recreation opportunities presented by the Upper Cumberland.

Cookeville is also home to Tennessee Technological University, better known as Tennessee Tech.

Cookeville has three interesting facets that make it a stop on our itinerary.

The first is WCTE, a PBS affiliate that began broadcasting in 1978. WCTE is the only television station in the entire 14-county Upper Cumberland region. That’s right. No NBC, ABC, CBS, CNN or Fox.

On its website, WCTE states its mission is “to establish lifelong learning and cultural storytelling by connecting the Upper Cumberland to the world and the world to the region.”

The station was featured in a December 2020 story on “CBS Sunday Morning” on the 50th anniversary of the Public Broadcasting System.

In that report, we learned that WCTE is one of 80 PBS stations in rural, underserved areas of the country. Most parts of the Upper Cumberland have no Internet and, at best, spotty cell phone service.

Residents of the Cookeville region told “CBS Sunday Morning” they are grateful for the programming they receive from their local station.

What WCTE provides fits in with what the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 had in mind when it declared: “It is in the public interest to encourage the development of programming… that addresses the needs of unserved and underserved audiences, particularly children and minorities.”

PBS, which was created by the 1967 act along with National Public Radio (NPR), now has more than 355 member stations that provide programming for 66 million viewers every month as well as 60 million who use PBS’ website and social media.

The first show broadcast by PBS was a cooking show by Julia Child. Since then, PBS has been the host of well-known programs such as “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” “Sesame Street,” “Masterpiece Theater” and “Downton Abbey.” The network also been the site of numerous documentaries by filmmaker Ken Burns.

PBS receives $450 million in federal funds each year. WCTE gets about $600,000 of that money.

The chief executive officer and president of WCTE until recently was Becky Magura. She grew up in Cookeville and started at the station as its first student intern.

Another Cookeville native is Richard Froning Jr.

Froning graduated from Cookeville High School in 2005 and from Tennessee Tech in 2009.

He became well known in the sports world after he won the CrossFit Games individual championship four years in a row from 2011 to 2014.

After his titles, Froning was hired as an assistant strength coach at his college alma mater. More importantly, the CrossFit Mayhem gym he opened in 2009 became an international draw.

His fitness center, which is on Rich Froning Way, has attracted many of the best CrossFit athletes in the world. They now live and train in Cookeville, making this rural Tennessee town a mecca for the sport.

There’s a little musical celebrity status in town, too.

Jake Hoot, the winner of the 17th season of “The Voice” in 2019, played football at Tennessee Tech. He still lives in town.

Hoot is giving back to his community. He has donated $15,000 to each of three charities. The money was raised from the sale of Hoot merchandise while he was competing on “The Voice.”

One of the organizations to receive money is the local Habitat for Humanity chapter. So, like Froning, Hoot has a street here, too. Jake Hoot Drive is in one of the Habitat projects in town.

The Heart of Country Music

It’s another hour and 15 minutes on Interstate 40 west before you reach the Tennessee state capital of Nashville.

The community along the Cumberland River has grown to nearly 680,000 residents, making it the most populous city in the state as well as the 21st most populous in the country.

Nashville is well known for its connection to country music, but it also has been a major inland port and a center of higher learning. It even has a replica of a famous structure in Greece to honor its dedication to education.

Native tribes of the Mississippi culture first moved into the region about 1000. They grew corn, painted pottery, made dirt mounds and then mysteriously disappeared around 1400.

The first European settlers were French fur traders who established a post in 1717. The town was founded in 1779 by English pioneers and named for Francis Nash, a general in the Continental Army.

Nashville grew quickly due to its port along the Cumberland as well as its network of railroads.

It did suffer from a cholera epidemic that began in 1849 and lasted into 1850. More than 300 people were killed, including former President James Polk just three months after he left office. Polk’s post-presidency remains the shortest retirement of any U.S. president.

During the Civil War, Nashville was highly sought by Union forces because of its port. They captured the city in 1862, making it the first Southern state capital to fall.

After the war, Nashville developed a manufacturing base to go along with its port and railroads.

The city also developed a history of racial problems.

The Ku Klux Klan struck early, holding a meeting in Nashville in 1867 in which the organization’s first grand wizard was selected.

In 1892, Ephraim Grizzard was lynched by a mob that suspected him and several other Black men of assaulting two white teenage girls. In June 2019, an historical marker was installed downtown to remember Grizzard as well as his brother, Henry, and two other Black men who were publicly killed in the Nashville area after the Civil War.

In 1960, the home of City Councilman Z. Alexander Looby, who was also an attorney for African-American activists, was bombed. There’s now an historical plaque at the councilman’s former home.

In 1967, there were race riots at three colleges in the Nashville area in which gunfire was exchanged between protesters and police. Injuries and property damage were reported. The protests began after speeches by Black leaders that encouraged their constituents to take the reins of economic power in the city.

And in 1979, the Klan burned crosses at two locations, one of which was the offices of the local chapter of the NAACP. The fiery demonstration occurred in the midst of a debate over the removal of a bust in the state Capitol of a Confederate general who was a co-founder of the Klan.

Despite all this violence, some successful Black neighborhoods did rise. There are ongoing efforts to preserve some of the historic buildings in these areas.

The city received an economic boost in 1997 when it was awarded a National Hockey League expansion team, a squad that was eventually named the Nashville Predators. In 1998, the Houston Oilers moved their football team to Nashville and became the Tennessee Titans.

In 2017, Nashville was named one of the fastest growing cities in the country. That year was when Nashville surpassed Memphis as Tennessee’s most populous city.

The music industry is a major player in the economy for decades.

The city is a center for music recording and production. It’s estimated that the industry provides 43,000 jobs in town and has an economic impact of $15 billion.

The Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, Tennessee. was once home to the Grand Ole Opry. Photo by Tennessee Encyclopedia.

Among other things, Gibson Guitar has been headquartered here since 1984. The Gibson Garage guitar store opened in June 2021, allowing musicians to try out and purchase every brand of the company’s guitars.

Along 16th and 17th avenues is a district known as Music Row, full of recording studios and production offices. The district got started with the opening of RCA Studio B in 1957. At a traffic circle, there is the Musica statue, a 40-foot-high piece of artwork unveiled in 2003 that displays nine bronze nude dancers floating in the air and has been criticized by some in town as being obscene. It’s considered to be the largest bronze figure group in the country.

The Grand Ole Opry is another landmark. The Opry began as a radio show in 1925. It has had a number of different locations over the years, including a famous 31-year run at the Ryman Auditorium. The Opry has been held at the Grand Ole Opry House northeast of downtown since 1974, although concerts are still performed at the Ryman during the winter months. The show was popular on radio through the 1950s. It made its television debut in 1955 and had several versions during the decades that followed. The Opry returned to television in 2020 on a new network known as Circle TV.

Nashville is also home to the Country Music Hall of Fame. Its mission is to “preserve, celebrate and share the important cultural aspect that is country music.”

The hall opened in 1967 on Music Row and has been in its current location downtown since 2001. It now contains 200,000 recordings, 500,000 photographs, a 776-seat theater and exhibits that display famous musicians’ clothing and cars. More than 1 million people visit in a typical year.

The Johnny Cash Museum is also downtown. It contains the world’s largest collection of artifacts from the country music legend known as “The Man in Black.”

Another component of Nashville’s economy is higher education.

The city is home to Vanderbilt University, a private research institution founded in 1873 with a $1 million gift from industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt. The 13,000-student university has 10 schools on a park-like campus.

Tennessee State University also calls the city home. Tennessee State was founded in 1912. The 500-acre campus now enrolls more than 7,600 undergraduate students.

Due to its educational institutes, Nashville quickly became known as the “Athens of the South.” In 1897, a full-scale replica of The Parthenon in Greece was built for the city’s centennial celebration. The complex also serves as Nashville’s main art museum and houses 63 paintings by American artists.

Nashville also has a strong healthcare component. More than 900 healthcare companies have operations here. The industry contributes 550,000 jobs and $97 billion in economic impact to the city.

Nashville is also going to get a bit bigger in the coming years.

In 2019, a development firm announced plans to build 600 apartments as well as offices and 50,000 square feet of retail space on land the group has purchased along the Cumberland River. A ground-breaking ceremony was held in October 2021 as the first phase of construction began. The 125-acre River North project will include a pedestrian bridge that connects the Germantown district with eastern Nashville. It also will have a marina and waterfront park.

The real estate market remains hot here. The median price for a home in Nashville is listed at about $430,000.

We’ll settle in here to end the 20th leg of our trip.

Today was a dash through central Tennessee.

Tomorrow we cut through another region of the state on our way to Kentucky.

Along the route we will visit two towns connected to the childhood of my grandfather.