Day 26: From Jersey to Connecticut’s Gold Coast

April 14, 2021

Day 24: Chocolate, Pretzels and Mushrooms in Pennsylvania

April 12, 2021Most recently updated on March 25, 2024

Originally posted on April 13, 2021

The sun rises over the great city of Philadelphia, the birthplace of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as well as the home of the Liberty Bell.

The city where Benjamin Franklin and Betsy Ross lived. The town where Rocky Balboa ran up the 72 steps leading to the Philadelphia Art Museum.

Boathouses, murals and cheesesteaks. A lot to see and taste here today.

First, though, we make a side trip to check out two sites that were important parts of the Revolutionary War.

From downtown Philly, we take Interstate 95 in a northeasterly direction, skirting the Delaware River as well as the New Jersey border. Before I-95 takes a hard right and becomes the New Jersey Turnpike, we veer onto Interstate 295 and head due north.

After 40 minutes, we arrive at Washington Crossing Historic Park, which sits across the Delaware River from the Washington Crossing State Park in New Jersey.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, this is the spot where General George Washington crossed the Delaware not once, but twice, in late December 1776.

Washington Crossing Historic Park on the Delaware River in Pennsylvania. Photo by visitPA.

The first crossing happened on Christmas night when Washington and 2,400 troops left their encampment at McConkey’s Ferry and quietly glided 300 yards across the icy Delaware and landed near what is now Trenton, New Jersey. They used sturdy Durham cargo boats, which were 40 to 60 feet in length, to transport soldiers as well as 18 cannons.

Among Washington’s men were future presidents James Monroe and James Madison as well as future secretary of the treasury Alexander Hamilton, future vice president Aaron Burr and future Supreme Court justice John Marshall.

The next morning, the American soldiers surprised a group of 1,400 German soldiers known as Hessians who were fighting for the British. The group of Hessian soldiers surrendered after an hour and a half of fighting. In all, 22 Hessians were killed and nearly 900 were captured. Only four Americans died. Washington’s squadron returned across the Delaware later that day with prisoners as well as muskets, powder, artillery and other supplies.

The first attack was so successful, Washington decided to try it again. He correctly guessed that British troops on the other side of the river were not expecting American revolutionary forces to make a repeat trip over the frigid waters. Spies also told the British that Washington’s army seemed to be tired, cold and not going anywhere.

“To them, there was nothing to worry about,” said Thomas Maddock, one of the interpreters at Washington Crossing Historic Park.

On December 30, Washington’s brigade once again slipped across the Delaware. On January 2, they defeated British troops stationed near Trenton. The next day, they overwhelmed a rear guard near what is now Princeton before retreating to their winter quarters in Morristown, New Jersey.

The famous painting of the initial crossing was completed by a German artist in 1851. While the painting captures the drama of the moment, historians say there are several things that are historically inaccurate. For starters, the painting shows a U.S. flag that didn’t come into existence until the following year. It also depicts an older Washington as he looked when he was president. The general was 44 years old at the time. In addition, it shows Washington standing, although he was most likely sitting while in a rowboat on choppy waters.

The revolutionary forces’ two victories were not strategically significant, but they cemented Washington as the leader of the Continental Army and injected morale into the American side. In December 1776, many colonists did not think their ragtag fighting force could defeat the mighty British, especially after Washington’s army had been chased out of New York and New Jersey.

“Washington knew something offensive had to happen,” Maddock told 60 Days USA in spring 2021. “He had to get some good news for the cause.”

In addition, many of the enlistments in Washington’s army were due to expire at the end of that month. The Delaware crossings convinced some of them to stay.

So did money.

Maddock said Washington had promised recruits who stayed past December 31 an extra $10. However, he didn’t have any money. So, he sent word to Robert Morris, a delegate to the Second Continental Congress who played a major part in financing the war. Morris quickly raised $50,000 and sent the cash to Washington.

“Without the money, I don’t think Washington would have had an army,” Maddock noted.

In Maddock’s mind, the importance of the crossing cannot be overstated.

“It was literally one of the major turning points of the American Revolution,” he said. “If this hadn’t worked, heaven only knows, we might all be speaking British.”

The historic crossing is detailed in “American Ramble,” a book by Wall Street Journal journalist Neil King Jr. about his 330-mile walk from Washington, D.C., to New York City in spring 2021. During his journey, King and a friend paddled kayaks across the Delaware at the spot where Washington’s army crossed.

The historical event is also remembered at Washington Crossing Historic Park, a 500-acre preserve that includes the spot where the colonial army crossed the river as well as 13 historic buildings. One of those structures is the McConkey’s Ferry Inn, where Washington and his commanders reportedly ate dinner while they planned the initial raid. There’s also the Durham Boat Barn with five replicas of the watercraft Washington’s troops used.

In addition, there’s an upper park area 5 miles away with the site of a hospital and the graves of several dozen soldiers who died at the winter encampment.

The Pennsylvania park was founded in 1917 and was designated as a national historic landmark in 1961.

Across the river is New Jersey’s Washington Crossing Historic Park.

This 369-acre area is part of the national historic landmark. It’s also a wildlife habitat.

The New Jersey park includes the spot where Washington’s army landed as well as Goat Hill Overlook, a place where Washington may have stood to assess battle conditions. There’s also the Johnson Ferry House that may have been used by Washington and his commanders after their crossing.

The Delaware River, by the way, is a 405-mile waterway that starts in the Catskill Mountains in New York and winds through five states before dumping into Delaware Bay.

The town of Washington Crossing in Pennsylvania is a community of 4,500 people that is 89 percent white. The median annual household income here is $194,000 and the average price of a home is about $900,000.

The village is within easy commuting distance to Philadelphia and several New Jersey cities.

Maddock said the median income and the average home price may be driven up by some large McMansion-type houses on the north side of town.

He says the core of Washington Crossing is much the same as when he grew up here as a kid from 1936 to 1951.

Maddock, his wife and others conduct 1-hour tours of the historic park.

————————————-

While the winter of 1776 was a success for George Washington and his Continental Army, the winter of 1777 was one of misery and endurance.

That’s when Washington’s garrison of 12,000 soldiers as well as 400 women and children camped at Valley Forge from December 19, 1777, to June 19, 1778.

Valley Forge is now a small village about 45 minutes west of Washington Crossing.

In 1777, it was the winter encampment for Washington’s army.

The location was selected because it was close to Philadelphia but far enough away to discourage British attack. It also sat on a plateau and had water on three sides, making it relatively easy to defend.

Valley Forge National Historic Park in Pennsylvania. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

Washington’s soldiers built hundreds of log cabins here that were 14 feet by 16 feet long and 6 feet high. The roof was wood board and the floor was dirt. There was a stone fireplace, but little else to keep the occupants warm. Straw was often used instead of blankets. Each cabin housed about a dozen men. Among them were Monroe, Hamilton, Burr, Benedict Arnold and the Marquis de Lafayette. Martha Washington also spent some of that winter at Valley Forge.

Snow fell on most days and temperatures dipped into the 20s and 30s. For the first three months, few supplies got through. The only water was what could be drawn from the nearby streams. Food became scarce. Uniforms turned threadbare.

Poor sanitation and hygiene led to rampant disease. Illnesses such as typhus and dysentery killed as many as 3,000 of the soldiers. Another 1,000 were seriously ill. A hospital was built in nearby Yellow Springs to care for the sick. More than 50 other buildings such as barns became makeshift medical centers.

In early March, the situation began to change.

General Nathanael Greene took over the transportation of food, clothing and other supplies. Those items started coming regularly by wagon. A group of 70 bakers also arrived, producing daily bread for the famished soldiers. Fish began to appear in the streams and were snared for hearty meals. Farmers also started bringing in fruits and vegetables.

Baron von Steuben, a former Prussian army soldier, was brought in to shape up things. He observed an army that didn’t do a daily roll call and had soldiers who didn’t know how to march correctly or properly use a bayonet. Von Steuben instituted training and drills. The unit improved dramatically and fresh soldiers began to arrive. Morale was further boosted when the men at Valley Forge learned that France had joined the war on their side.

The troops marched out of Valley Forge a better trained and motivated Army, confident they could defeat the Red Coats. That spring, the British retreated from their positions in Philadelphia and headed back to New York. The Valley Forge contingent quickly moved into Philadelphia.

In “American Ramble,” King also describes how harsh that 1777 winter was and how Valley Forge evolved into an important historical site. It didn’t happen overnight.

Today, the army’s winter home is the Valley Forge National Historical Park, a 3,500-acre region of monuments, woods and pastures that preserves the encampment and provides interpretation of that winter’s hardships. Visitors can see historic structures such as Washington’s headquarters as well as reconstructed versions of the log cabins.

The Birthplace of American Democracy

It’s just a half-hour drive down Interstate 76 from Valley Forge to Philadelphia.

The city is so full of history and culture, it’s difficult to know where to begin.

So, let’s start at the beginning.

Native American tribes began inhabiting this region about 10,000 years ago. The first European settlers were the Dutch, who arrived in 1615. They built Fort Nassau on the Delaware River in 1623.

William Penn founded the city in 1682 after he received a royal charter for the Pennsylvania colony. Penn signed a peace treaty with the Lenape tribe and named the settlement after the Greek words for “brotherly love.”

He planned the city to be a port along the Delaware River as well as a hub for peace and religious freedom.

That freedom wasn’t immediately extended to African-Americans. In 1684, the first slave ship arrived in Philadelphia. The citizens were quick to establish a movement against slavery. In 1688, members of Quakers organized the first New World protest against slavery. The American Anti-Slavery Society was eventually formed here.

In its first decades, the city became the largest shipbuilding center in the country.

Philadelphia was instrumental in the American Revolution as a meeting place for the Founding Fathers. The Declaration of Independence was signed here at the Second Continental Congress in 1776. It was also the site where the Constitution was drafted in 1787.

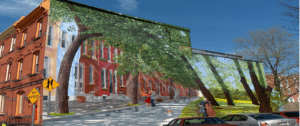

Philadelphia is well known for its murals. Photo by SpokenVision.

Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800 while Washington, D.C., was under construction. It was the most populous city in the country until New York overtook it in 1790.

Philadelphia was a major industrial center and a railroad hub. Textiles and shipbuilding were among the main industries. It was also the first city to have a library, hospital, medical school and zoo.

Those industries fired up during the Civil War, supplying the Union side with ships, weapons and uniforms.

During the 1800s, there was an influx of immigrants from Germany, Italy and Ireland. In the 1900s, African-Americans from the South arrived as did people from Puerto Rico.

The city’s population doubled to 2 million between 1890 and 1950. The increase in numbers as well as diversity brought about racial tensions. In 1919, Philadelphia was one of a number of cities where racial riots occurred in what became known as the “Red Summer.”

Tensions between police and African-Americans have simmered for decades. In 1964, Philadelphia was the target of one of the first civil rights demonstrations of that decade. In 1985, police dropped a bomb on the roof of a home occupied by African-American activists in the MOVE organization. The resulting fire killed 11 people inside and burned down adjacent homes. In October 2020, protests broke out after police officers shot and killed 27-year-old Walter Wallace Jr.

Today, Philadelphia remains a city with a rich ethnic mix. It has the fourth largest African-American community as well as the second largest Italian, Irish, Jamaican-American and Puerto Rican populations among U.S. cities. It also has a large, active LGBTQ population with a high-profile Gayborhood section near Washington Square.

Philadelphia was also the U.S. center for the 1918 flu pandemic with 500,000 people contracting the disease. Nearly 12,000 Philadelphians died. The illness was initially spread by a Liberty Loan parade attended by 200,000 people.

Philadelphia had to live through another pandemic from 2020 to 2022. In April 2022, the city reinstituted mask mandates as COVID-19 cases began to rise again. Restrictions were eased in summer 2022 as cases began to decline once more.

The city’s economy has had to become more diverse after the shipyards and other factories closed. Financial services are the largest sector. There’s also a biotech hub and the 1,200-acre refurbished Navy Yard, which is now home to a mix of retail, office, industrial and research facilities with 15,000 employees working for 170 companies. A new phase of development began in 2021 that will redevelop another 109 acres of property. In June 2022, plans were unveiled for a development that includes 611 residential units as well as life science buildings and a hotel.

In January 2022, the city was informed it would receive $1.6 billion to repair up to 3,000 bridges in poor condition under the $1 trillion infrastructure bill signed by President Joe Biden in 2021. In July 2023, workers completed a 12-day repair job on the collapsed I-95 bridge.

Philadelphia is also considered the world capital of murals. The program began in 1984 with Mural Arts Philadelphia as an anti-graffiti project. It’s now the largest public art program in the nation. There are more than 4,000 community-based works of public art in the city with 50 to 100 new pieces commissioned each year.

Artwork and historical landmarks were some of the reasons Philadelphia was named a World Heritage City in 2015, the first such designation in the United States.

The City Center area has been transformed into a “walkable downtown.”

That’s helpful as there is a lot of U.S. history on display downtown. One of many reasons the city receives more than 40 million tourists in a typical year.

The Liberty Bell near Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Photo by the National Park Service.

We can start with Independence Hall, the place where the First and Second Continental Congress met and the Declaration of Independence was signed. The Constitution was debated and drafted in this building. The structure, which was slowly built between 1732 and 1753, includes an exhibit hall where an original draft of the Constitution was signed. An inkstand used to sign the Declaration of Independence and George Washington’s “rising sun” chair are also displayed.

Across the street is the Liberty Bell Center, where the famous 2,000-pound copper and tin artifact is on exhibit. The Liberty Bell hung in the tower of the Pennsylvania State House and was rung to mark historic occasions, including the first reading of the Declaration of Independence. The last chimes were in 1846 to celebrate George Washington’s birthday. The bell’s signature crack is actually a repair job, which was done to widen a smaller initial crack to keep the damage from spreading. It didn’t work. A second smaller crack appeared and the bell was put into retirement.

Three blocks away is the Museum of the American Revolution, which showcases the “compelling stories and complex events that sparked America’s ongoing experiment in liberty, equality and self-government.” The array of exhibits examines how colonists turned into revolutionaries and the new nation they created.

Just a block or so from here is the Benjamin Franklin Museum. The facility is dedicated to the life and work of Franklin, who came to Philadelphia from Boston in 1723 at the age of 17 and became well known as an inventor, publisher and founding father. The museum is divided into five rooms, each focused on a particular trait of Franklin. There are also “ghost” frameworks in the courtyard where Franklin’s house and print shop were located.

Not too far away is the Betsy Ross House, the 250-year-old home that Ross was renting when she purportedly sewed the first U.S. flag. Ross was born Elizabeth Griscom on New Year’s Day in 1752. Although Ross is often referred to as a seamstress, she was actually a trained upholsterer. After completing her formal education at a school for Quaker children, Ross went on to apprentice under John Webster, a talented and popular Philadelphia upholsterer. She spent several years under Webster, learning to make and repair curtains, bedcovers, tablecloths, rugs, umbrellas and Venetian blinds.

While apprenticing to Webster, Ross met and fell in love with a fellow apprentice named John Ross, an Anglican and son of the former assistant rector of Christ Church. She eloped and married him at age 21. The couple started an upholstery business. In May 1776, the story goes, the 24-year-old Ross was asked by George Washington and two other colonial activists to sew that first U.S. flag. Ross was widowed twice and married three times. She died at the age of 84 in 1836.

There’s plenty of history outside the downtown area, too.

Boathouse Row in Philadelphia. Photo by Wikiwand.

Along the banks of the Schuylkill River to the northwest is Boathouse Row. It consists of a line of 15 boathouses, the oldest built in 1860. Most others are around 100 years old. The boathouses are used by rowing clubs, among other groups. The buildings are now a national historic landmark.

Not too far away are the 72 stone steps that lead up to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. These steps were used by Sylvester Stallone in his “Rocky” movies. The film’s main character would charge up the steps whenever he was in top shape before a fight. A “Rocky” statue that was crafted in 1980 for the “Rocky III” film was installed at the bottom of the steps in 2006. The statue as well as the steps are a favorite spot for tourist photographs.

Another tourist favorite are Philly Cheese Steak sandwiches. The famous meals are made from thinly sliced beefsteak with melted cheese on a hoagie roll. Toppings can include onions, green peppers, mushrooms, ketchup, hot sauce, salt and pepper. The sandwiches were created in 1932 at a hot dog stand in South Philadelphia. Cheese wasn’t added to the recipe until 1949.

Like most cities, Philadelphia is dealing with a number of urban issues.

One is an ongoing trash problem that has produced the nickname “Filth-adelphia.” The issue is somewhat simple. There aren’t enough trash collectors and street sweepers to pick up all the garbage out on the street.

Philadelphia has also struggled over the years with economic issues. Up until 2010, the city suffered from decades of declines in jobs, a rise in poverty rates and an exodus to the suburbs. In the past decade, the city was starting to see a bit of a turnaround even though poverty and affordable housing were still major concerns.

Many of these issues have been covered in depth by the city’s main newspaper, The Philadelphia Inquirer. The paper was first published in 1829. It’s a publication known for investigative pieces that have brought it 20 Pulitzer Prizes.

After 2006, the paper went through a series of ownership changes before becoming the property of the nonprofit Lenfest Institute for Journalism in 2016. A 2019 report by the Neiman Lab stated that the institute has made some investment into the newspaper, but that the paper still struggles with financial issues and morale problems.

The Inquirer’s fiscal situation is not uncommon in the country’s daily newspapers, as we discussed in a Spotlight story on our site.

The major issues facing the city had landed on the desk of Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney for 8 years. He was the city’s 99th mayor and the latest in a string of Democratic leaders in a city that hasn’t had a Republican mayor since 1948. Kenney did not seek a third term, so the city got a new mayor in November 2023 when Democratic former city councilmember Cherelle Parker won by a wide margin and became the city’s 100th mayor and the first female mayor of Philadelphia.

In November 2021, Mayor Kenney signed legislation that prohibits police from stopping motorists for seven types of minor vehicle infractions, including non-working taillights and a non-visible license plate. Fines are now mailed to vehicle owners. The new rules took effect in early 2022.

A lawsuit was also filed against the mayor’s administration in April 2021 by Italian-American groups angry that the city has changed the Columbus Day holiday to Indigenous People’s Day. In August 2021, a judge ruled in favor of an Italian-American group’s request to leave standing a statue of Columbus in Marconi Plaza. In October 2021, though, the city celebrated Indigenous People’s Day instead of Columbus Day. The same celebration was held in October 2022. The lawsuit against the mayor’s administration was dismissed by a federal appeals court in January 2023.

A lot to absorb on this full day in the Philadelphia area.

Tomorrow, it’s back on the road through New Jersey and New York before we settle down in one of the richest regions in the country.