Day 37: From North to South Through Ohio

April 25, 2021

Day 35: Rumbling Through the Rust Belt

April 23, 2021Most recently updated on February 6, 2024

Originally posted on April 24, 2021

We depart from Pittsburgh by heading north on Highway 65 as it hugs the eastern shoreline of the Ohio River.

This stretch of road covers the first 25 miles of the Ohio’s 979-mile length, making it the 10th longest river in the United States.

The waterway begins in Pittsburgh and flows through or borders six states before it merges with the Mississippi River in Cairo, Illinois, just south of St. Louis, Missouri. At that juncture, the Ohio is actually larger than the Mississippi. In fact, the Ohio is the largest tributary by volume to the Mississippi.

“Ohio” means beautiful river in the language of the native tribes that lived along it and used it as transportation for centuries. Europeans first glimpsed the river in 1669. The first Anglo to travel on the waterway from beginning to end was Arnout Viele, who did so in 1692.

In the late 1700s, the Ohio served as the southern boundary of the Northwest Territory. In his book, “The Pioneers,” author David McCullough describes the voyages of the people who traveled on the river to reach destinations in this new and mostly unexplored region.

Eventually, the Ohio River served as an extension of the Mason-Dixon Line that separated free states from slave states. At the river’s narrowest points, such as Cincinnati, fugitive slaves would cross the waters to escape to freedom. Slaves that were caught were “sold down the river” along the Ohio and Mississippi back to their plantations. That’s where the phrase originated.

Throughout the 1800s, the Ohio served as a major transportation route for travel as well as for shipping goods from Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois.

In its natural state, the Ohio ranged from 3 feet to 20 feet deep. The more than 20 dams now along the river have changed the make-up of the waterway. The average depth is now 24 feet with its deepest point in Louisville at 168 feet.

The river is still used by barges to transport oil, coal, steel and other goods. The Ohio carries an estimated 230 million tons of cargo per year. It also has 49 power generating stations and provides drinking water to more than 5 million people.

This well-used waterway does suffer from the effects of pollution.

People who fish are routinely warned not to eat what they’ve caught. The Allegheny Front environmental journal reported in 2020 that there are 40,000 permits in the Ohio River watershed allowing entities to discharge wastewater. Of those, nearly 7,000 are considered toxic releases. Environment America reports that in 2020 heavy industry dumped more toxic materials in the Ohio River watershed than any other watershed in the United States.

There are a number of major sources for the river’s pollution.

Raw sewage is reportedly discharged at more than 1,300 points during rainstorms. The chemical PFOA used to make Teflon is reportedly discharged into the river from a DuPont plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia. There’s also acid mine pollution on the upper Ohio, partly from discharges from the steel mills along the river banks. And there is so-called “nutrient pollution” from the agricultural uses that make up about 35 percent of the Ohio River basin.

All of these factors led the organization American Rivers to declare in April 2023 that the Ohio is the second most endangered river in the United States, behind only the Colorado River.

Organizations such as the Environmental Law & Policy Center are advocating measures to improve water quality in the Ohio River. Among the proposals are establishing pollution control standards, limiting nutrient runoff and requiring polluters to pay for clean-up efforts. The Ohio River Foundation also has an ongoing public education campaign.

In November 2021, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine announced the state will spend $5 million on wetlands projects to improve the water quality in the Ohio River Basin.

————————————-

After 25 miles of northward trajectory, the Ohio River takes a sharp turn westward. At that bend is the town of Monaca, a community of 5,400 people where the economy may soon be dominated by at least one, if not two, major chemical complexes owned by large oil companies.

The local economy here was quite different when settlers first arrived.

The land was granted to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1787. It was sold in 1813 to Frances Helvidi, an exiled Polish nobleman who raised sheep. The property was sold again in 1821 with residents first arriving in 1822 and setting up boat yards on the Ohio River.

In 1832, German immigrants moved in and formed a religious community. Some of them moved downstream, but there are descendants that remain in Monaca to this day.

A “water cure sanitarium” was established in 1848. In 1865, a home for soldiers’ orphans opened. In 1892, the town was named Monaca after the Oneida warrior chief Monacatootha.

Manufacturing slowly developed over the years with factories producing porcelain ware, glass, tubing and wire. Anchor Hocking has a glass manufacturing plant here. That plant was sold in 2021 to Stoelze Glass Group of Austria.

The Beaver Valley Power Station nuclear power plant was supposed to be closed in 2021, but its owners changed their mind. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Another big regional employer is the Beaver Valley Power Station nuclear power plant in nearby Shippingport. In 2018, the former owners of the facility announced plans to close its two power-generating units that employ 1,000 people. However, in March 2020 officials at Energy Harbor Corporation, which now operates the plant, said they were rescinding that decision and planned to keep the 1,800 megawatt power station open.

They said the main reason for the reversal was the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative signed in 2019 by Governor Tom Wolf. The initiative is a cap-and-trade program whose goal is to limit carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. Energy Harbor said the initiative would “begin to help level the playing field for our carbon-free nuclear generators.” However, Pennsylvania’s participation in the program is now in flux. In November 2023, a court ruled that the state has imposed an unconstitutional tax to join. State officials are appealing the decision as well as seeking legislative action.

Another large energy-related complex has opened in the Monaca area.

Shell Chemical Appalachia has finished construction of a $6 billion petrochemical complex at a 386-acre former zinc site near town. The plant is developing natural gas into plastic pellets. It’s expected to produce as much as 1.6 million metric tons of pellets per year. The complex has its own set of pipelines and its own rail system with 3,000 rail cars.

Automobiles and Amish

As the Ohio River swerves westward, we continue northward.

Eventually, we make our way to Interstate 76, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and head northwest.

In a half-hour, we say goodbye to Pennsylvania and hello to Ohio. We’ll be in the Buckeye State for most of the next three days.

Ohio is only the 34th largest state in terms of size, but its nearly 12 million people make it the 7th most populous, behind Illinois and ahead of Georgia.

The first European settlements were trading posts for the fur industry in the 1700s. After the French and Indian War in the 1750s, France ceded the territory to Great Britain. After the Revolutionary War, Great Britain handed over the land to the United States.

The Ohio area was part of the Northwest Territory before it became a state in 1803, the 17th to join the Union. It was mostly wilderness and started out with an agricultural economy.

As pioneers moved westward, Ohio developed into a cargo processing and distribution center because it linked the Northeast and Midwest via the National Road, the Ohio River and the railroads.

Later in the 1800s, it became an industrial powerhouse, first with coal mining and then iron production. That strong economic activity lasted for more than 100 years, but, as we shall see over the next couple days, as the country’s industrial economy began to fade in the second half of the 1900s, some of Ohio’s well-known cities took a hit.

As the 2000s dawned, Ohio leaders started to make a slow shift to the technology and information industries. The change has had some impact, but the state’s largest industries are still manufacturing and transportation/trade. Ohio remains the nation’s leading producer of plastics, rubber, fabricated metals, electrical equipment and appliances.

In January 2019, Ohio began allowing the sale of medical marijuana. Some supporters see the drug’s legality as an answer to the state’s opioid addiction epidemic. The state now has more than 90 state-licensed operating cannabis dispensaries. In November 2023, voters approved a measure allowing recreational cannabis to be sold in the state. That product is expected to start being dispersed in fall 2024 after state officials finalize rules regarding its sales.

Ohio also has a long history of anti-abortion legislation. A law in Akron that included a 24-hour waiting period and an “informed consent” provision was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1983. In 2018, legislation was approved that banned the most common abortion method used in the second trimester of pregnancy. In December 2018, Governor John Kasich vetoed a “heartbeat” bill that would have prohibited abortions after six weeks of pregnancy. In 2019, an appeals court upheld an Ohio law that prevents state funding of healthcare operations such as Planned Parenthood that provide abortion services. After the June 2022 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down Roe v Wade, Ohio instituted the 6-week abortion restrictions. The new rules made national news when a pregnant 10-year-old rape victim was denied an abortion. That law was blocked by a judge while a constitutional challenge made its way through the courts. However, in November 2023, Ohio voters approved a measure that enshrined abortion rights into the state constitution, in effect eliminating the 6-week ban.

Ohio does have a number of historic firsts. The nation’s first traffic light was installed in Cleveland in 1914. Akron was the first city to use police cars. The country’s first hot dog was served up here in 1900.

Finally, Ohio is the birthplace of seven U.S. presidents. Only Virginia with eight has had more. Ohio has adopted the nickname “Mother of Presidents.”

—————————————-

A half-hour after crossing the Ohio border, Interstate 76 takes us just south of the former steel center of Youngstown and into Lordstown, a village of 3,300 people that has been in the spotlight in recent years due to its car manufacturing industry.

The town was home to the Lordstown Assembly, a General Motors factory that began operating in 1966. The 6 million square foot state-of-the-art plant with robotic welders had a peak employment of 12,000 workers in 1976. It was one of the largest employers in northeastern Ohio after the steel industry collapsed in Youngstown.

The plant was in the news in 1972 when employees went on strike. The action led to the phrase “Lordstown Syndrome” for when workers are bored and depressed during monotonous assembly line duties.

General Motors considered closing the factory in 2002 but didn’t. The Lordstown facility also survived GM’s 2009 bankruptcy filing.

In November 2018, however, General Motors announced it was shuttering the factory in spring 2019 because the company was discontinuing the Cruze model. Company officials said it was focusing less on sedans and more on trucks and other larger vehicles as well as self-driving and electric cars.

The last Chevy Cruze rolled off the Lordstown assembly line in March 2019. In its time, the Lordstown plant manufactured 16 million cars. That included 2 million Chevrolet Cruze vehicles since 2011.

In June 2019, GM executives announced they were negotiating to sell the plant to Workhorse Group, an electric vehicle start-up that critics noted had lost $150 million since 2007 and had less than $3 million cash on hand. The deal was signed in November 2019.

A model of an electric truck at Lordstown Motors’ new plant in eastern Ohio. Photo by Industrial Equipment News.

In November 2020, the new Lordstown Motors, with the backing of Workhorse Group, opened a plant to manufacture electric pick-up trucks in the old GM factory. The plant’s plan was to provide 450 union jobs with preference given to former GM employees.

However, it’s been a bit of a rocky road for Lordstown Motors. In March 2021, their stock plunged after an investment firm accused the company had misled investors about its demand and production capabilities. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission launched an investigation and some shareholders filed a lawsuit.

Nonetheless, state officials said the plant was a key to Ohio’s automotive future. Steven Burns, Lordstown Motors chief executive officer, dismissed the investment firm’s report and said the first electric trucks would roll off the assembly line here in September 2021.

However, financial difficulties delayed those plans and in November 2021, it was announced that Taiwan-based Foxconn would purchase the Lordstown factory. Foxconn is best known for manufacturing Apple iPhones.

In September 2022, the first handful of Endurance electric pick-up trucks were assembled. Company officials said they expected to deliver 50 trucks to customers by the end of 2022 and 450 more during the first half of 2023. Reaching that goal got off to a poor start. In February 2023, Lordstown Motors halted production amid production and quality issues after selling only six vehicles. In May 2023, it was reported that Foxconn and Lordstown Motors were at odds over investments that Foxconn was supposed to have made. In June 2023, Lordstown Motors officials announced they were filing for bankruptcy protection, putting the company up for sale and suing Foxconn over promised investments. In October 2023, Burns purchased the company’s assets. It’s unclear if the plant will continue production.

What has happened in Lordstown is symbolic of what has happened to the U.S. auto industry in general. You can read more about this rise, fall and rebound in our Spotlight feature on the history of manufacturing in the United States.

Despite the struggles in Lordstown, the electric truck factory here is seen as a potential harbinger of an automotive revival in the United States. The Time magazine article discusses how other places in Ohio as well as states such as Tennessee are trying to position themselves for a piece of this new “green” market. Indeed, in late September 2021, Ford Motors announced it plans to build an electric F-150 truck assembly plant and three battery manufacturing centers in Kentucky and Tennessee. The facilities are expected to open in 2025 and create 11,000 jobs. In May 2022, Ford unveiled plans to build electric vehicles at its Ohio Assembly Plant in Avon Lake near Cleveland, creating 1,800 union jobs. In October 2023, it was reported that full electric vehicles were having a record year in sales, representing nearly 8 percent of the market. There are currently 2.4 million electric vehicles registered in the United States in an industry valued at nearly $50 billion.

Despite the problems with Lordstown Motors, there is an emergence of related industries in town.

In July 2020, construction began on a $2.3 billion battery cell plant on 158 acres next to the former GM plant. It’s a joint venture between GM and LG Chem of South Korea. The factory is expected to provide 1,100 new jobs. The facility powered up in March 2022. In July 2022, LG Chem announced it had signed a deal to supply batteries to General Motors.

——————————————–

We head north out of Lordstown on Highway 45 through rural northeastern Ohio.

At the town of Warren, we bend in a northwesterly direction on Highway 422 before we direct ourselves north again on Highway 528 until we hit the town of Middlefield.

The community of 2,700 has been a prosperous village for 200 years. It even has a Walmart super center that caters to their small town economy. That’s why there are hitching posts for buggies in the parking lot. More on that in a moment.

Middlefield was first settled in 1799 by James Thompson and his father, Isaac Thompson. In 1818, James Thompson built a hotel that eventually became the Century Inn and now houses the local historical society.

The town’s initial industries included furs, grains, cheese and black salts that were transported to Pittsburgh. In 1873, a narrow gauge railway was built through town. The first manufacturing business was the Johnson Pail Company, which eventually became the Johnson Rubber Company.

Today, the manufacturing base includes the Gold Key Processing rubber compounding factory now owned by Hexpol. There’s also KraftMaid, which manufactures kitchen cabinetry. Duncan yo-yos have been produced here since the 1930s. Middlefield Cheese specializes in Swiss cheeses and has a chalet in town.

Agriculture remains a staple with horse breeding, dairy farming and crops such as corn, wheat and soybeans. Trade is also important as 44,000 vehicles pass through town each day.

Middlefield is the center of the fourth largest Amish settlement in North America. It’s also the second largest such community in Ohio, which has the highest number of Amish citizens of any state.

The Walmart Supercenter in Middlefield, Ohio, has hitching posts for Amish customers to tie up their horses. Photo by Ars Technica.

The Amish are a Christian group mostly located in North America. The religious order was formed in Europe in the late 1600s by followers of Jakob Ammann. The Amish immigrated to North America in the 1800s and 1900s, disappearing from the European continent. An old order, which sticks to traditions, and a new order, which accepts some societal change, branched away from each other.

The old order Amish are known for their plain, handmade clothing. Men sport long beards but do not grow mustaches. Amish women don’t cut their hair nor do they wear jewelry. They don’t own vehicles. Instead, they ride bicycles or guide horse-drawn buggies. Electricity is not part of their home life unless it’s necessary to operate a buggy or do essential chores such as milking cows. Musical instruments are also prohibited in old order households.

Amish settlers first moved to Ohio from Pennsylvania in 1808. Ohio has 60,000 Amish living in 52 settlements with more than 400 church districts.

The largest settlement is in Holmes County with 30,000 residents. Geauga County is second with 12,000 residents. Middlefield is part of that congregation.

The influence of the Amish is seen throughout the town.

Many earn a living by farming, doing manual labor or running a small business. Among them are shops with hand-crafted items. There’s also Mary Yoder’s Amish Kitchen just north of downtown.

However, perhaps the most obvious indicator of Amish presence in Middlefield is at the Walmart Supercenter. There are hitching posts out front for Amish customers to park their buggies. Inside the store carries blocks of ice for refrigeration as well as fabrics for homemade clothing.

In August 2022, a new law took effect requiring Amish buggies and other animal-driven carriages to be equipped with flashing yellow lights.

All Along the Lake

We continue north on Highway 528 before we backtrack a bit east on our friend from Buffalo, Interstate 90.

In less than an hour, we reach the town of Ashtabula, a community of 17,000 people along the shores of Lake Erie that once was one of the world’s busiest ports as well as a vital component of the Underground Railroad.

Native tribes lived beside the lake for centuries. Ashtabula, in fact, comes from an Algonquin word that means “river of many fish.”

The first European settlers didn’t arrive until 1801. The town quickly developed as a port trading center due to its location on the lake and its proximity to inland transportation.

By 1830, Ashtabula was considered to be the third largest receiving port in the world as well as the busiest port on the Great Lakes.

The Pittsburgh, Youngstown and Ashtabula Railroad was built in 1873, allowing the port here to bring in coal and iron ore from Minnesota and then transport the materials to the steel mills in Youngstown and Pittsburgh.

The industrial growth brought in immigrants from Finland, Sweden and Italy. Eventually, ethnic rivalries developed, so in 1915 Ashtabula became the first U.S. city to adopt proportional representation where the percentage each political party received in an election determined what percentage of legislators they had. Another 24 cities adopted this system, although Ashtabula ended it in 1931.

The political differences didn’t slow down the activity along the shores of Lake Erie. In the 1960s, Ashtabula was still the third busiest iron ore port in the world and hit its peak population of 24,000.

Coal and iron ore are still transported into Ashtabula but not in the quantities they once were. The chemical industry is now a primary user of the port.

At one point, the Rockwell International factory that was here manufactured brakes for the space shuttle program. Other companies manufacture automobile parts, fiberglass and plastics.

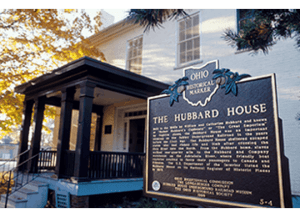

The Hubbard House Underground Railroad Museum in Ashtabula, Ohio. Photo by the Ashtabula County Visitors Bureau.

As we’ve seen in other cities, all this industrial activity has led to the pollution of local waterways. The Ashtabula River and nearby Fields Brook as well as the harbor itself were designated as a Superfund project in the 1990s. The cleanup lasted until 2013 and included the dredging of the river. The site is still monitored by federal officials.

A $139 million cleanup was in operation between 1998 and 2006 at the former RMI plant in town. The factory conducted titanium extrusion operations as part of a federal energy department program from 1962 to 1988. The cleanup was ordered due to radioactive contamination left over from the plant’s operations on the 7-acre site.

The economy does appear to have stumbled since the port’s heyday. The median annual household income is about $36,000 and the poverty rate is 31 percent.

There’s a home in town that is a tribute to an important part of Ashtabula’s past.

The Hubbard House was built by William and Katharine Hubbard in 1841. It was one of the northern terminus points for the Underground Railroad used by runaway slaves to reach freedom.

Ashtabula’s location on Lake Erie became particularly important after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was approved. The law required people in free states such as Ohio to hand over any runaway slaves caught in their territory.

The fugitive slaves would hide in houses in places such as Ashtabula and then take a boat across Lake Erie to freedom in Canada.

It’s unknown how many slaves found refuge in the Hubbard home, but there are accounts of dozens of them being there at one time.

The home is now the site of the Hubbard House Underground Railroad Museum. There’s also an annual Underground Railroad Pilgrimage in October that begins at the Hubbard House and visits 18 other spots in the county that were important locations for runaway slaves.

————————————–

We’ll stay close to Lake Erie as we turn westward for today’s final destinations.

Highway 20 takes us out of Ashtabula and provides a wide view of the southern shores of the lake.

Lake Erie is the second smallest of the five Great Lakes with a surface area of 9,910 square miles, although it is still the 11th largest lake in the world.

It’s also the southernmost, the shallowest and the smallest in volume of the Great Lakes. Its deepest depth is 210 feet with its average depth being 62 feet. The lake’s shallowness makes it the warmest of the Great Lakes but also the first to freeze in winter.

Erie is 210 miles in length stretching on its southern side from Buffalo, New York, to Toledo, Ohio. The states of Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York all touch its shore. It begins with water flowing in from the Detroit River and finishes downstream at the Niagara River in Buffalo. It also has 31 islands.

Lake Erie has the largest population of the five Great Lakes with 12 million people living in its watershed.

Settlers began to arrive in numbers in 1809 thanks to the Talbot Trail. In the 1850s, fisheries were established. That was also the same decade that railways began to circle the lake.

Lake Erie supplies about half the fish caught in the Great Lakes, earning itself the nickname of “Walleye Capital of the World.” Sturgeon are also starting to make a comeback due to new stocking efforts. The sturgeon is still listed as an endangered species in Ohio, so any that are caught must be released back into the water.

The shores of Lake Erie. Photo by Public Domain Pictures.

There is also a lot of agriculture on the lake’s shores with Canadian farmers growing vegetables and operating wineries.

Wind farms could also be a formidable industry here. Steel Winds south of Buffalo opened in 2007.

There were plans for a 20 megawatt Icebreaker Wind facility near Cleveland. If built, it would be the first offshore wind project on the Great Lakes. It would also be the first freshwater offshore wind power facility in North America. Supporters say it could help wean large Midwestern cities off fossil fuels, but opponents say it’s too costly and its impacts on the environment are unknown. Groups such as Save Our Beautiful Lake have formed to try to stop the project. However, in August 2022, the Ohio Supreme Court cleared the way for the project and its six turbines to be built. Nonetheless, in December 2023 the Lake Erie Energy Development put the project on indefinite hold, citing rising costs and opposition.

The Great Lakes Wind Council was formed in 2009 to try to find a balance between energy needs and environmental protections for the Great Lakes.

The strong winds here do create waves and other hazardous conditions. That’s why there is an estimated 1,400 shipwrecks on the lake’s bottom.

The environmental concerns on Erie include overfishing, pollution and algae bloom. The algae bloom in summer 2019 was the fifth largest recorded since 2002. Environmental groups filed a lawsuit in 2019 asking for mandatory regulations. In 2022, the algae bloom was reported as less serious than in recent years. The Alliance of the Great Lakes says algae blooms endanger the drinking water of 11 million people as well as harm the ecosystem. Other groups say climate change is making the algae growth worse. Plans are in the works to toughen regulations on the runoff into the lake that causes the blooms.

————————————–

A 45-minute jaunt along Lake Erie takes us to the town of Mentor, a community of 46,000 that was the site of the 1800s version of a virtual presidential campaign as well as a school that’s been spotlighted for its anti-bullying campaign.

The region was first settled in 1797 by Charles Parker who built a cabin on a marsh along Lake Erie. The town grew due to its proximity to the lake as well as the Ohio and Erie canals. It was named after the Greek character Mentor in “The Odyssey.”

In 1876, Mentor captured the fancy of Ohio congressional representative James A. Garfield, who purchased a farm and a home to accommodate his large family. The farm was originally 118 acres before Garfield added 40 more acres. He expanded the home in 1880 from nine rooms to 20 rooms.

In 1880, Garfield staged a “front porch campaign” for president from his estate. He didn’t hit the road to solicit votes. Instead, he gave speeches from his home, which reporters called Lawnfield. Voters and journalists came to his house to hear what he had to say.

The campaign was successful. Garfield was elected president, defeating Civil War General Winfield S. Hancock by about 10,000 votes. That remains the smallest popular vote margin in presidential election history.

Some other candidates adopted Garfield’s strategy in the ensuing decades. Benjamin Harrison won in 1892 with a front porch style of campaign. So did William McKinley in 1896 and Warren G. Harding in 1920.

After that, it seemed that the days of the stay-at-home campaign were over.

The home in Mentor, Ohio, where James A. Garfield ran his successful “front porch” presidential campaign in 1880. Photo by TheArmchairExplorer.com.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020 and Democrat Joe Biden spent much of the early part of his successful presidential campaign courting voters and donors from the basement of his home in Delaware as technology such as FaceTime and Zoom allowed Biden to campaign virtually.

Garfield’s time in the White House was brief. In July 1881, just four months after being inaugurated, he was shot in the back at a train station by a deranged gunman. Garfield lived for two more months before dying in September.

Garfield’s wife, Lucretia, lived in the home in Mentor until she died in 1918. Her brother then resided there until his death in 1934. The family donated the house and its contents to the Western Reserve Historical Society for a museum.

The James A. Garfield National Historic Site was designated as a historic location in 1980. The property was transferred to the National Park Service in 2008. It contains the memorial library built inside the home by the family in 1885. It was the first presidential library in the country.

In the 1800s, Mentor was a farming community and a distribution center due to its proximity to the lake and canals.

However, by the 1930s the town had earned the nickname of “The Rose Capital of the World” because of its plentiful supply of rose bushes. Many people worked here as florists and horticulturists.

After World War Two, the construction of new highways turned Mentor into a commuter suburb of Cleveland. It also developed an advanced manufacturing industry with products such as plastics, aerospace equipment, biotechnology, polymers, automotive parts and components.

The city is also known for its 300 retail stores and its 175 restaurants. The Convenient Food Mart chain has its national headquarters in Mentor.

The town seems to have done well economically. Its median annual household income is nearly $84,000. The poverty rate is listed at less than 5 percent.

However, Mentor did have a dark secret.

In 2010, CBS News did a story on four Mentor High School students who had died in a two-year span after being bullied. Three were by suicide and the other was an overdose on antidepressants. In 2014, Amazon released a documentary called “Mentor” that focused on the families of two of those children.

A lawsuit filed by the parents of Eric Mohat against the school district was settled in 2014. Another lawsuit filed by the parents of Sladjana Vidovic was dismissed in 2015.

Mentor certainly isn’t the only community facing this issue.

The federal government estimates that about 20 percent of students ages 12 to 18 nationwide experience bullying. The aggressive behavior takes place on campuses as well as online, a form of harassment known as cyber-bullying.

The bullying actions range from being called names to being the subject of rumors or lies to being shoved or tripped to being excluded to being threatened with harm. Experts say bullying can affect not only those who are harassed but also those who do the bullying as well as those who witness it. The aftereffects can last well into adulthood.

In Mentor, the public school system has released a series of vision statements on bullying that call for a “safe and secure environment in which students can grow academically and socially.” The schools also participate in the “Stick Together” nationwide antibullying campaign.

Rockin’ It in Cleveland

It’s only a half-hour down westbound Interstate 90 to get from Mentor to Cleveland, our final stop on today’s route.

The city of 354,000 is the second most populous in Ohio, behind only Columbus. It’s a diverse population that’s listed as 46 percent Black, 34 percent white and 12 percent Hispanic or Latino.

Cleveland’s history is a prime example of the struggles and attempted revivals of our nation’s industrial centers. However, it’s also the place where you can savor rock ‘n’ roll music, pay homage to our country’s female aviators and visit a house that was the setting for one of the country’s most popular Christmas movies.

The Erie and Iroquois lived along the lake shoreline here for centuries. The settlement was established in 1796 by surveyors from the Connecticut Land Company led by Moses Cleaveland. The crew laid out 220 lots at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River.

The community was incorporated as a village in 1814 and named after the survey party leader. The name was shortened, however, in 1831 when the Cleveland Advertiser dropped the first “a’ so the town’s name would fit on its masthead. The settlement was incorporated as a city in 1836.

The town grew slowly at first due to a lack of adequate transportation. Rapid growth occurred after the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal in 1832. Merchants could now send goods to the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. The growth increased when the railroads arrived in the 1850s.

Like many Ohio cities, Cleveland developed into a commercial center due to its location between the Midwest and the East Coast. Iron ore, coal, copper, lumber and farm goods all moved through town.

Steel production began in the 1860s. John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in Cleveland in 1870.

In the early 1900s, Cleveland was a manufacturing center that included a number of automobile companies. The available jobs attracted European immigrants as well as Black and white migrants from the South. Bootleg liquor was also smuggled in from Canada during the Prohibition era.

In 1920, Cleveland was the nation’s fifth most populous city.

The Great Depression hit the town hard with one-third of the workforce being unemployed at one time. The industries bounced back during World War Two when Cleveland was one of the more important manufacturing centers in the nation. Its population peaked at 915,000 in 1950.

The Christmas Story House Museum in Cleveland, Ohio, is a popular tourist attraction. Photo by Thought & Spirit.

In 1967, Cleveland became the first major U.S. city to elect a Black mayor when Carl Stokes was sworn in.

In 1969, the city was in the national news for its “burning river.” It happened on June 22 when floating pieces of oil-covered debris in the polluted Cuyahoga River were ignited by sparks from a passing train. The flames reached as high as 50 feet and the fire lasted for nearly 30 minutes. This incident was the 13th recorded fire on the river since 1868.

The attention the 1969 blaze received led to the passage of the National Environment Policy Act of 1970. That law helped establish the Environmental Protection Agency. One of that new agency’s first policies was the 1972 Clean Water Act. Since then, more than $3 billion has been spent to clean up the Cuyahoga River.

In the 1970s, Cleveland’s industries began to falter. In 1978, it became the first major U.S. city since the Great Depression to declare financial default on its federal loans.

Starting in the 1990s, redevelopment helped revive the downtown. New sports arenas as well as a number of museums helped boost the economy.

Since 2000, the city has tried to diversify its economy with gains in the medical industry and the arts. Like Pittsburgh, Cleveland is considered an example of an old industrial city reinventing itself. The Republican Party showcased that element when it held its 2016 national convention here.

The city still has a way to go, however.

Its median annual household income sits at $37,000 with a poverty rate of 31 percent. The median price for a home is slightly less than $100,000.

Since 2008, the Evergreen Cooperative Corporation has been doing their part to turn that around.

The non-profit organization creates employee-owned businesses that provide jobs and boost the regional economy. Some of the original enterprises include the Evergreen Cooperative Laundry.

In 2018, Evergreen launched a program to create 10 more owner-operated businesses that would employ 600 people through the Fund for Employee Ownership program. The fund purchases private businesses in the Cleveland region and converts them into employee-owned operations.

So far, the fund has turned at least three businesses into employee cooperatives.

The organization’s programs also have the goal of providing jobs for people who have been released from prison after serving time.

Their focus has been in the Greater University Circle neighborhood where the median household income is less than $20,000 per year.

The Cleveland organization is part of a small but growing nationwide trend.

In February 2020, a Pew Trusts report estimated that there are about 400 worker-owned cooperative businesses in the United States. Another 6,300 companies have employee stock ownership plans.

The report noted that worker cooperatives have had supporters from both sides of the political aisle over the years from Republican President Ronald Reagan to Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren.

Cooperative businesses efforts like those sponsored by Evergreen got a boost in 2018 with the passage of the Main Street Employee Ownership Act.

Cleveland parks officials are also trying to revamp part of the city’s shoreline with Lake Erie.

In April 2021, officials at Metroparks unveiled a plan to convert part of the city’s East Side lakefront into tranquil coves and wetlands. The proposal calls for using recycled sediment from the bottom of the Cuyahoga River to create 80 acres of parkland along the shore, including a new Erie Island. The project could take 15 to 25 years to complete.

In the meantime, Cleveland has a variety of current sites for visitors to see.

As you enter the city from the east, there’s the Lake View Cemetery. The tomb of John D. Rockefeller is here. A tradition is to leave a dime in honor of Rockefeller’s habit of giving dimes to children. The cemetery is also the burial place of President James Garfield and FBI agent Eliot Ness, who was safety director for Cleveland in the 1930s before he went on to “The Untouchables” fame.

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland is designed to look like a record player. Photo by Wikiwand.

A little south of downtown is the Christmas Story House. This is the actual house used for Ralphie’s family in the 1983 holiday classic “A Christmas Story.” The home was renovated in 2006 to look like it did when the movie was filmed nearly 40 years ago. You can actually rent the house for an overnight stay. The Christmas Story Museum is located across the street and contains items such as pink bunny suits and replicas of the movie’s iconic leg lamp.

Just north of downtown is the International Women’s Air & Space Museum, located in the terminal building at Burke Lakefront Airport. The center pays tribute to the country’s women aviators and space travelers. Many of the artifacts have been collected by the Ninety-Nines, an international organization of women pilots formed in 1929.

A few blocks away is perhaps Cleveland’s best-known museum.

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame opened in 1995 and in a typical year will receive 500,000 visitors. The facility is designed to look like a record player. The exhibits include Michael Jackson’s sequined glove, the Boy Scout uniform of The Doors’ Jim Morrison, the Pink Floyd Wall and Elvis Presley’s motorcycle. There’s also lots of musical tributes as well as displays of past induction ceremonies.

Cleveland was chosen as the site for the museum because local DJ Alan Freed is credited with coining the term “rock and roll” in 1951 to establish the style of music as separate from rhythm and blues.

The 2022 inductees included Pat Benatar, Duran Duran, Dolly Parton, Eminen, Lionel Ritchie and Carly Simon. The 2023 inductees included Sheryl Crow, Willie Nelson and Missy Elliott.

You can listen to your favorite tunes at any number of music-themed restaurants in Cleveland.

One of the best known is the Jukebox, a music-centric tavern in Cleveland’s Ohio City neighborhood.

We covered a lot today, but our tour of Ohio has just begun.

Tomorrow, we cut through the center of the state and end up at one of the more historic cities along the Ohio River.

Some famous chili will be on the menu.