Day 36: Getting to Know Ohio

April 24, 2021

Day 34: From Laughter to Remembrance

April 22, 2021Most recently updated on February 5, 2024

Originally posted on April 23, 2021

Today, we get our first glimpse of the Rust Belt and the impact the industrial decline of the past few decades has had on some of the great manufacturing towns of our country.

We start by heading west out of Somerset on Interstate 76, a freeway that runs from New Jersey to Ohio.

A half-hour down the freeway we find the town of Acme, a hamlet of less than 4,000 people. What puts the community on our radar is a place called Polymath Park. It’s an enclave with four homes, two of which were designed by famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The Duncan House was built in 1957 and the Mantyla House was constructed in 1952. Both were moved from different parts of the country. These two houses as well as the other two Wright-inspired homes in the park can be rented overnight by visitors who want to experience what it’s like to stay in a prairie-style house designed by Wright.

After another 15 minutes on the road, we pass through the town of New Stanton, a community of about 2,200 residents that has seen factories come and go and then return again.

The region was originally occupied by the Mound Builders and then by the Mingo, Shawnee and Delaware tribes.

European settlers laid out the community along the old Somerset to Pittsburgh Road in the early 1800s. The grain crop couldn’t be easily transported to the Midwest at that time, so locals made whiskey and delivered that product to Pittsburgh.

In 1852, the Stanton Rolling Flour Mill was built. In the 1870s, industries such as salt wells, iron furnaces and stone quarrying emerged.

In 1940, the Pennsylvania Turnpike opened and was touted as the country’s first “super highway.” Indeed, 2.4 million vehicles roared through annually in its first few years.

Volkswagen operated a plant in town from 1978 to 1988. It manufactured the Rabbit, Jetta and Golf, employing 5,700 people from the region at its peak. More than 200,000 cars rolled out of the factory during its decade of operation.

The New Stanton plant was the only Volkswagen factory in the United States during that time. The plant closed in 1988 when sales of the company’s smaller cars declined. Volkswagen eventually opened another factory in Tennessee. The 350-acre site in New Stanton was taken over by the Regional Industrial Development Corporation.

In 1990, RCA opened a factory producing television sets. The plant employed 3,000 people in the late 1990s. That number had dwindled to 250 by 2007. The factory shut its doors in 2010. That left 2.8 million square feet dormant. The development corporation has since leased 1 million of that square footage to companies that now employ about 1,000.

New Stanton does have two distribution centers that employ more than 2,000 people in the region.

UPS has a sorting operation center that handles 400,000 packages daily and employs 1,700 workers in a 322,000-square-foot facility.

SuperValu operates a 720,000-square-foot distribution facility that serves Shop N Save, Save-A-Lot and Country Market stores. About 500 people work there.

The local economy seems to be doing OK. The median annual household income is $71,000 and the poverty rate is less than 1 percent.

—————————————-

Steel, economic distress and air pollution are all on the agenda a few miles up the road.

The town of Clairton is about a half-hour from New Stanton. The quickest way there is to hop on Interstate 70 west for a few miles before heading north on Highway 51.

Clairton was founded in the early 1900s when the Crucible Steel Company bought a large tract of land along the Monongahela River and formed the Clairton Steel Company. In 1904, Carnegie Steel, which would later become U.S. Steel, took over Clairton Steel and built a steel mill and coke refinery in town.

The community was incorporated as a city in 1922 when it had 11,000 residents.

The city’s economy powered along until the 1950s when the steel industry started to decline. The U.S. Steel plant closed in 1962.

The coke plant does remain in operation. Clairton Works is the largest coke manufacturing facility in the United States. It still operates 10 coke oven batteries and produces 4.3 million tons of coke per year for the commercial market as well as for U.S. Steel operations. It employs about 1,000 people, down from the 4,000 workers it had in the 1970s.

The Clairton Works coke factory in western Pennsylvania has been the source of air pollution complaints. Photo by Pittsburgh Tribune-Review

That hard-working factory has raised concerns about the quality of air that Clairton residents breathe.

In June 2018, Allegheny County officials fined U.S. Steel $1 million for chronic air pollution violations. In February 2020, county officials and U.S. Steel representatives agreed to a settlement that requires the company to pay $2.4 million in fines and spend $200 million to upgrade the Clairton plant. In March 2022, U.S. Steel was issued another $4.6 million in fines by the county for 86 air pollution violations since January 2020. The company was hit with another $458,000 in fines by Allegheny County officials in December 2022 for air pollution violations during the first three months of the year. Environmentalists said the fines show that U.S. Steel is willing to “pay to pollute” rather than modernize equipment.

The group Penn Future started a petition drive in 2019 to get U.S. Steel to upgrade its coke facility, which contains equipment that has been used since the 1950s. The organization delivered petitions with 5,300 signatures to the company. U.S. Steel has countered by saying it made $50 million in modernization improvements in 2018 and has hired 50 more employees.

In March 2023, U.S. Steel officials said they were moving forward with plans to shut down three of the 10 coke batteries at the plant. They said they would reassign rather than lay off the 130 employees affected.

Even with the jobs remaining at the coke factory, Clairton has struggled since the decline of the steel industry.

The city was the bleak setting for the opening scenes of the 1978 movie, “The Deer Hunter,” although the film was not shot locally.

The city was declared a distressed municipality in 1988 after laying off its entire police force and reporting a $680,000 budget deficit. It held that status for 27 years until finally being removed from the state list in 2015.

Lincoln Way, once a nice part of town, became an abandoned neighborhood of 52 pieces of unused property.

The community now has 5,800 residents, a fraction of its high of 25,000 citizens decades ago. The population today is listed as 52 percent white and 40 percent Black. It has a median annual household income of $41,000. Its poverty rate sits at nearly 23 percent.

Falling Glass and Failing Steel

There are more stories of decline and attempted renewal as we travel along the Monongahela River as it heads toward its juncture with the Allegheny River to form the mighty Ohio River.

Just 3 miles north of Clairton is the borough of Glassport, which is literally a shell of its former self.

The community once boasted a population nearly 9,000 people, but it now contains less than 4,300 residents. Most of the blame can be laid on a single tornado.

Glassport used to be part of the Elizabeth Township until it became its own municipality in 1902.

The population of Glassport, Pennsylvania, has declined to less than 4,300 residents. Photo by Wikipedia.

The town was built around the United States Glass Company, which had opened a mill here in 1894. The community was laid out by the Glassport Land Company, a subsidiary of U.S. Glass. The factory became known as the “The Glass House.”

The plant made pressed glass products such as tableware and other items produced from glass molds. In 1940, Glassport hit its peak population of 8,700 residents.

All was chugging along fine until August 1963 when an F3 tornado plowed through town. The windstorm knocked over the factory’s 80-foot-high water tower and sent it crashing through the roof of the glass factory. The furnaces shut down and all the molten glass inside hardened. All that was left behind was a 250-ton block of solid glass.

The tornado also damaged the Petrosky Hotel, killing two people inside.

U.S. Glass determined it was too expensive to repair their factory, so they shut it down. The company went out of business in 1963.

After the closure, Glassport’s population declined to its current 4,300 residents and the town never quite recovered.

————————————-

A similar story can be found a little farther up the Monongahela.

The community of Duquesne is about 6 miles north of Glassport.

The formerly thriving steel town once hosted a population of 21,000 with a world class steel mill humming at all hours. Today, the community has about 5,000 citizens.

The first steel plant here was the Duquesne Steel Works, which opened in 1886. In 1888, the factory was purchased by the Carnegie Steel Company. The complex helped propel Andrew Carnegie to the forefront of the steel industry.

By 1916, the city’s population had reached 19,000 people. Carnegie Steel had become U.S. Steel. By 1918, the company’s Duquesne Steel Works had 33 open hearth furnaces and 12 rolling mills.

The Duquesne factory was the heart of the town and a big piece of the U.S. steel industry. In 1920, the plant had grown to 6,000 employees.

The town reached its peak of 21,000 people in 1930. By 1948, Duquesne mill was employing 8,000 people.

In 1950, the population had slipped to 17,000 with 16 percent of them foreign born. African Americans made up close to 10 percent of the work force.

The Dorothy 6 Blast Furnace Cafe is a tribute to the former industries in Duquesne, Pennsylvania. Photo by the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

In 1963, the Duquesne factory christened its sixth blast furnace, calling it the Dorothy 6 after the wife of the president of U.S. Steel. It was the largest and most modern of its kind. Dorothy 6 operated for 20 years, lighting up the city’s night sky. Bob Dylan’s 2012 song, “Duquesne Whistle” is dedicated to the furnace. There’s also a Dorothy 6 Blast Furnace Café in nearby Homestead.

Like many towns in western Pennsylvania, deindustrialization started here in the 1960s. The steel mill closed in 1984, laying off the 1,200 workers who were still there. The plant was demolished in 1988. A historical marker was placed on the site in 1997.

In 1991, Duquesne was designated as a financially distressed municipality. In 2019, city officials said they hoped the city could be taken off that list in the near future. It hasn’t happened yet.

The town’s population is listed as 44 percent Black and 38 percent white with a median annual income of $40,000 and a poverty rate of 25 percent. The median home price is less than $50,000, having decline 6 percent in the past year.

Schools in the area have also struggled.

In 2007, state officials overseeing the school district closed Duquesne High School and sent its students to neighboring cities. In 2017, the nearby West Mifflin School District reached an agreement with Duquesne school officials over funding they provide West Mifflin for teaching their students. However, in June 2022, the district announced that 7th and 8th grade students would return to Duquesne and plans were under way to eventually reopen the high school.

The biggest sector of Duquesne’s economy today is healthcare and social assistance.

The steel mill’s former 250-acre site is mostly abandoned. A 10-story pile of blast furnace slag has been restored as a green space.

The site does contain an 11-acre facility for the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank.

The work this food bank and others are doing is discussed in a Spotlight report on hunger on the 60 Days USA website.

From the Top to the Bottom

As much as the other western Pennsylvania towns on today’s route have had their ups and downs, the town of Braddock may have them all beat when it comes to highs and lows.

Consider these disparities.

Braddock, which is just 3 miles across the Monongahela River from Duquesne, was the site of Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill, a factory that is still operating and is the final one of its kind left in Pennsylvania.

The town was also the site of the first of Carnegie’s more than 1,600 public libraries.

Its former mayor is now one of the two United States senators from Pennsylvania.

On the flip side, Braddock’s population now sits at 1,600. That’s less than 10 percent of its high-water mark of nearly 21,000 in 1920. It’s also the lowest population the town has seen since 1870.

The median annual household income is $27,000 and the median home price is less than $45,000 and declining.

It was designated as a financially distressed municipality for more than 30 years.

Today, the community is also dealing with a high infant mortality rate blamed on the toxic pollution left behind by its industries.

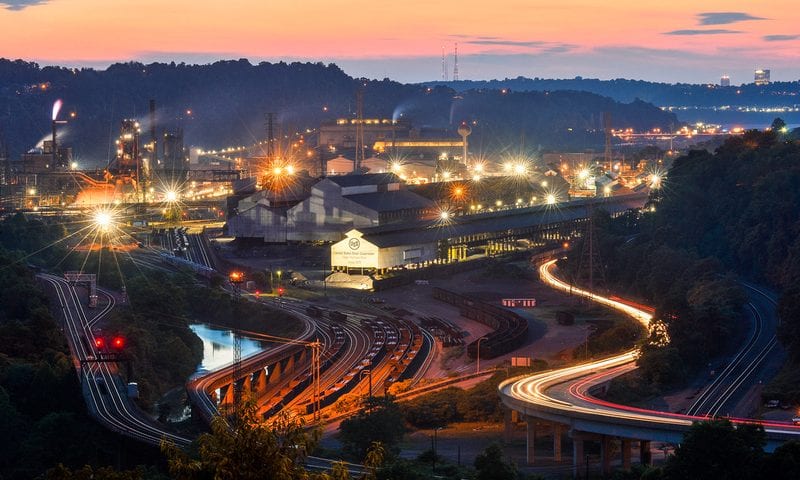

The Edgar Thomson Steel Works in Braddock, Pennsylvania, was Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill. Photo by Chris Litherland Photography.

Yet, the town hasn’t given up. There is a number of campaigns to revive the community.

The Braddock area was the site of a key battle in 1755 during the French and Indian War. In the Battle of Monongahela, British troops led by General Edward Braddock were defeated by a smaller force of French and Native American fighters. Braddock was killed during the fight and the town was named in his honor.

As that battle escalated, a young George Washington led the survivors on the British side to safety and gained a reputation for bravery. The battle site is now a Little League field. The Braddock’s Battlefield History Center, which opened in 2012, recalls the clash.

Braddock was settled in 1755. Its first industrial facility was a barrel factory that opened in 1850.

In 1873, Carnegie and his business partners built the Edgar Thomson Steel Works. It was Carnegie’s first steel mill and one of the first steel plants in the country to use the Bessemer process. The mill is now part of U.S. Steel Corporation and is still producing steel, nearly 3 million tons per year. In May 2022, U.S. Steel reached a settlement with the Environmental Protection Agency in which it agreed pay $1.5 million in penalties and upgrade its Braddock facility to settle air pollution violations.

Braddock was also the site of the first of Carnegie’s libraries. The industrialist contributed $40 million between 1886 and 1919 to help build his 1,679 libraries. His initial libraries were open only to his company employees. His first library open to the public was in the city of Allegheny, which is now part of Pittsburgh’s North Side.

The Braddock Carnegie Library was completed in 1888. It eventually contained a swimming pool, an indoor basketball court, a 1,000-seat music hall, a gym and a billiards room, all of which could be enjoyed by steel mill workers for a nominal fee. It should be noted that although Black steel workers could use the library, they were prohibited from using the other amenities.

The library was saved from demolition by a citizens group in 1978 and is still open. A major renovation began in September 2022.

Braddock was also the location of the country’s first A&P supermarket. The 28,000-square-foot store opened in 1936.

Like its neighboring towns, Braddock’s economy declined as the steel industry faded in the second half of the 1900s. The steel mill employed a peak of 5,000 workers during World War Two. It now employs about 600 people. Its two blast furnaces are the only ones left in Pennsylvania that produce steel.

In 1988, Braddock was designated as a financially distressed municipality. It stayed on that list until July 2023 when it was finally removed.

The city’s water distribution system was rebuilt in the early 1990s, but high levels of lead have been detected over the past 5 years.

Activists are trying to bring attention to the environmental problems here. One of their chief concerns is the high rate of infant mortality, especially among African-American babies. A four-part video series entitled “Braddock, Pa” chronicles some of the health issues.

Due to these environmental concerns, the group North Braddock Residents for Our Future was formed. One of its projects was to stop a proposal by a New Mexico-based oil company to drill and frack six gas wells on the U.S. Steel property. In December 2020, the project suffered a setback when an important permit expired and wasn’t allowed to be renewed. The project was shelved in 2021 by U.S. Steel. The organization is also involved in the Breathe Project, a program to clean up the air in the Pittsburgh area.

In addition to its low population and incomes, Braddock, a city that is now 80 percent Black and 15 percent white, also suffers from a poverty rate of 31 percent.

In 2005, Braddock began a slow attempt to try to revive its town.

It began with the election of John Fetterman as mayor. Fetterman arrived in town in 2001 as an AmeriCorps volunteer. He decided to stay and in 2005 was elected mayor by one single vote. He made it his mission to revitalize Braddock.

Fetterman threw his support behind a drive to attract new residents from artistic and creative communities. The mayor was known to buy abandoned homes for people in need of housing at no cost.

Fetterman also launched the Braddock Redux program, initially financed by his family’s money. The group’s stated goal is to mobilize young adults and other citizens for the overall betterment of Braddock through training programs, art initiatives, green projects and employment opportunities.

Fetterman also organized the Braddock Youth Project, a youth training program whose goal is to provide skills for youngsters to get them headed in the right direction in life. Since 2006, the young participants in the program have maintained community gardens in three locations in Braddock.

The city of Braddock website also spotlights some of the community programs and industries in town.

Braddock does face a dilemma seen in many former industrial towns. Do you provide new opportunities to former factory workers or do you try to bring their jobs back? You can read more about the status of U.S. manufacturing in another Spotlight story on the 60 Days USA site.

Fetterman served as mayor of Braddock for 13 years before he was elected lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania in 2018. In November 2022, Fetterman defeated Republican Mehmet Oz to win the open Pennsylvania seat in the U.S. Senate.

A City of Steel, Tech and Art

It’s just 15 minutes on westbound Interstate 376 to travel from Braddock to the metropolis of Pittsburgh.

The city famously sits at the juncture where the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers meet to form the mighty Ohio River.

Its population of 297,000 makes it the second most populous city in Pennsylvania, behind only Philadelphia and more than double the size of third place Allentown.

Pittsburgh is known as “Steel City” due to its 300 steel-related businesses. It’s also called the “City of Bridges” for its 446 bridges. Those spans include the Andy Warhol Bridge in honor of the famous artist who grew up here as well as the Roberto Clemente Bridge that was named after the baseball great who played right field for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Like nearly every community in western Pennsylvania as well as nearly city in the nation’s Rust Belt, Pittsburgh suffered through an economic decline when the country’s manufacturing base faded.

However, Pittsburgh has been able to bounce back by courting the high-tech industry and utilizing its higher education base as well as its artistic endeavors.

The Roberto Clemente Bridge is one of 446 bridges in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photo by Motion Array.

The Ohio River headwaters region was inhabited for centuries by the Shawnee, Seneca and Lenape tribes. The first European visitor was Robert de La Salle, who passed through during a 1669 exploration of the Ohio River.

The first European settlers arrived in 1764. The community was named after William Pitt the Elder, a member of Britain’s House of Commons who earned the respect of American colonists for his fair treatment of them.

Pittsburgh was laid out in 1784 and incorporated in 1816.

It didn’t take long for industry to sprout. The early businesses included shoemaking and tanneries. It was also a busy port that shipped whiskey, coal and salt. During the War of 1812, the city began producing iron.

The Pennsylvania Railroad arrived in 1854 and by 1857, Pittsburgh’s 1,000 industrial plants, which included 70 glass factories, were consuming 22 million bushels of coal a year. The black soot in the air earned it the nickname “Smoky City.”

Pittsburgh developed as a vital link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Midwest, earning the alternate moniker of the “Gateway to the West.”

The Civil War further boosted the economy as it created an additional surge of demand. Andrew Carnegie began producing steel in the region and formed U.S. Steel in 1901. The city accounted for nearly one-half of the nation’s steel production in the first half of the 1900s.

Factories also manufactured aluminum, glass, ships, petroleum, automobiles, electronics and food products. Industrialists H.J. Heinz and George Westinghouse also set up operations here.

European immigrants flooded to the city and African Americans transplants arrived from the South looking for work.

During World War Two, Pittsburgh factories operated 24 hours a day to produce 95 million tons of steel for the war effort.

In the 1980s, thousands of blue collar workers were laid off as the country’s manufacturing bases declined. However, technology industries were lured to pick up some of the slack. Today, there are 1,600 tech-related companies, including Google and Apple. In fact, Pittsburgh was ranked 13th in a June 2022 list of the top cities in the world for tech start-up businesses. A January 2023 report by the RAND Corporation recommended Pittsburgh bolster its science and technology workforce to keep up with the industry. All these changes have prompted city officials to rename their municipality from Steel City to Smart City.

The Duquesne Incline trolley provides great views of Pittsburgh. Photo by LiveAuctioneers.

The city is also home to at least 18 universities and colleges, including the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University. There are also several firms developing self-driving cars and trucks as well as a growing community of start-up companies, including AlphaLab.

In the Strip District, a number of former warehouses have been converted to shops, museums and restaurants. The city also boasts 29 skyscrapers now that are at least 300 feet tall.

Pittsburgh has been praised in recent years for turning its economy from blue collar to green collar. It also was ranked third in a September 2019 list of best Rust Belt comebacks.

Pittsburgh does have its obstacles to overcome.

For starters, its population has declined by more than 50 percent from its peak of 677,000 in 1950. Pittsburgh was the eighth most populous city in the country at that time. It’s now the 69th most populous, just behind the suburb of North Las Vegas in Nevada.

The city has struggled with air pollution issues caused by all the decades of heavy industry. At times, the city was described as being choked by a black film of sooty air. Several efforts known as “renaissances” have been implemented since the late 1940s to clean up the city’s air and water. Nonetheless, the city still received a failing grade for air quality in a 2020 report by the American Lung Association. The region also received an “F” in the association’s 2021 report. In its 2022 report, the association gave the Pittsburgh metropolitan area its first passing grade for fine particle pollution, but they noted the region still is among the 25 worst in the country.

Bicycle Heaven in Pittsburgh is the world’s largest bicycle museum. Photo by Discover the Burgh.

A big story involving air pollution in Pittsburgh is efforts by actor Michael Keaton, who grew up in the region, to open a new manufacturing plant here that will produce building panels that require 50 percent less energy to make than traditional concrete materials. The plant would emit fewer pollutants than a traditional factory.

Pittsburgh is also trying to heal from the October 2018 shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in which a gunman reportedly yelled anti-Semitic slurs as he killed 11 people. The massacre shook the Jewish community nationwide, in particular in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood where the synagogue is located. In June 2023, a jury convicted gunman Robert Bowers of all 63 federal charges filed against him. In August 2023, Bowers was sentenced to death.

In April 2019, the City Council approved three laws that restricted automatic-type weapons. A judge has struck down those restrictions and the city is now appealing that decision as well as asking state lawmakers to give the municipality the authority to enforce its laws.

There are a variety of sites for visitors to choose from when they come to Pittsburgh.

Point State Park sits at the confluence of the city’s three rivers. The 36-acre park was the location of Fort Pitt.

Nearby is the Duquesne Incline, a 140-year-old trolley system that takes visitors up Mount Washington for a grand view of Pittsburgh. The trolley opened in 1877 and now follows the path of an old coal hoist. It has 794 feet of track and an elevation of 400 feet.

There are four Carnegie museums in the city. One is the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. It’s considered one of the top natural history museums in the country. It focuses on science, nature and different cultures. Among its exhibits are dinosaur fossils, a hall of minerals and gems, and sections devoted to birds and North American wildlife.

There’s also the Heinz History Center, which details the history of western Pennsylvania. Among the exhibits in the 6-story complex is the TV set from the show “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” Fred Rogers grew up in Pittsburgh.

Another historical facility is the Andy Warhol Museum. It’s housed in a refurbished warehouse and is the largest museum focusing on a single artist in the country. It contains seven floors of exhibits of the works of the Pittsburgh native.

Finally, there is Bicycle Heaven. The museum and shop, which opened in 1996, contains nearly 6,000 bicycles. It’s the world’s largest bicycle museum.

It’s back in our car tomorrow as our tour of the Rust Belt region continues. We’ll head into Ohio with our final destination being a rockin’ city on the shores of Lake Erie.