Day 57: Pendletons and Ports in Eastern Oregon

May 15, 2021

Day 55: On the Road in Idaho

May 13, 2021Most recently updated on June 19, 2024

Originally posted on May 14, 2021

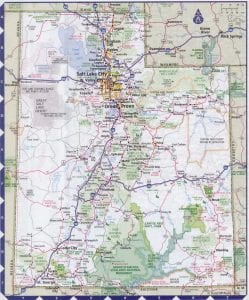

There are a lot of temples and other buildings in Salt Lake City that pay homage to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

But there’s also a shrine to honor the seagull. That bird played a historic role in Utah’s state capital, too.

That’s where we begin our journey on Day 56, a route that will take us to a place that helped the space shuttle program launch, an isolated area that’s an important part of our country’s railroad history and a bridge where people with parachutes love to perch and jump.

Salt Lake City is the most populous community in Utah with 211,000 residents. It’s 65 percent white, 20 percent Hispanic or Latino and sits at an elevation of 4,266 feet.

The Navajo, Ute, Pueblo and other tribes originally inhabited the area. John C. Fremont surveyed the area in 1843. The ill-fated Donner Party trekked across the valley in 1846 before getting stranded in the Sierra Nevada.

The city was founded in 1847 by Brigham Young and 147 followers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who were fleeing persecution in other areas of the country and found the valley mostly uninhabited, Young declared that “this is the right place” and immediately began planting crops and planning the Temple Square. Construction on the Salt Lake Temple began in 1853 and took 40 years to complete.

The Mormon pioneers built settlements and established irrigation systems. The religious followers originally called their area the State of Deseret after the honeybee, which became the state’s symbol. They named their community Great Salt Lake City after the nearby lake. The “Great” was dropped from the city name in 1868. Young had streets laid out in a grid pattern with the temple at the center. The city’s streets are wide because Young wanted people to be able to turn ox-driven wagons.

The dispute over the Mormons’ practice of polygamy reached a climax in 1857 when President James Buchanan sent 2,500 soldiers to install a non-LDS governor to replace the Mormon leader. Young declared martial law, leading to the Utah War. More troops were sent and forts were built, but no shots were fired. LDS members were jailed in the 1880s for violating polygamy laws. Citizens who practiced polygamy were also denied the right to vote or hold office. The church abandoned polygamy in 1890.

A boom sparked by the California gold rush led to gold, copper, silver and lead mines being developed between 1860 and 1920. In 1868, Young established the Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution, one of the first department stores in the nation. In the 1870s, rail links to the transcontinental railroad were completed and brought more economic growth. The city was nicknamed “Crossroads of the West.” Chinese immigrants who helped build the transcontinental railroad arrived and set up a “Plum Alley” neighborhood.

In the early 1900s, the state Capitol was built and a streetcar system was installed. The local economy suffered during the Great Depression with unemployment reaching 36 percent. The economy recovered in the World War Two era due to military institutions and demand for the region’s raw materials.

In the 1960s and 1970s as Salt Lake City residents began to move to the suburbs, the LDS church invested $40 million in a new shopping mall and other downtown improvements.

The University of Utah is a long-time institution here. The college was founded in 1850 and now has 26,000 students on its 1,500-acre campus.

The Seagull Monument in Salt Lake City, Utah. Photo by Waymarking.

There has been a recent influx of Hispanic residents as well as Asian immigrants. The city also has a growing LGBTQ community with the Utah Pride Festival during the first week of June being among the activities. The Sugar House neighborhood in the southeastern part of town, which is named after the sugar beet fields that were once there, has developed into a hip, progressive enclave.

Salt Lake City has battled a homelessness crisis for a number of years now. In 2020, the city opened three regional housing shelters to replace one large centrally located center. Observers said the new shelters had removed hundreds of people from the streets, but on-street encampments were a growing problem and housing waiting lists were long. In December 2021, city officials announced plans to re-evaluate the situation and better serve the homelessness. An investigative report stated that the city spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in 2021 on clean-ups at 50 homeless encampments. City leaders have instituted a moratorium on new homeless shelters and are asking other nearby cities to help ease the problem. In November 2023, the city opened its first sanctioned homeless camp, consisting of 27 small living units to house up to 50 people throughout the camp.

The economy here centers on state and federal government offices along with high tech and biotech industries. The city is also the industrial banking center of the United States.

In addition, Salt Lake City is the world headquarters of LDS church. Church leaders oversee operations in 160 countries from here. The headquarters’ Temple Square is the city’s number one tourist attraction with 1 million visitors in a typical year.

The city’s tourist industry also sees some economic activity every January from the Sundance Film Festival held in nearby Park City.

Tourism is also driven by outdoor recreation, especially skiing as evidenced by the city’s hosting of the 2002 Winter Olympics, an event that was deemed successful despite a series of bribery scandals. The Olympic Cauldron Park preserves the history and best moments from those Olympics.

There’s another monument to a success from the past here.

The Seagull Monument in Temple Square remembers the birds that swooped in from the Great Salt Lake in 1848 and devoured a horde of large, black crickets, saving that year’s winter harvest of 900 acres of wheat. In return, the seagull is honored as Utah’s state bird.

If you’re in the area, you might want to drink to your health with a Valley Tan, an alcoholic beverage made by Mormon pioneers from a blend of wheat and oat whiskey. The word “tan” comes from the leather tanning businesses owned by Mormon settlers. The word eventually came to mean anything that was homemade in the Salt Lake valley.

——————–

We see plenty of the valley as we retrace our steps from late yesterday on Interstate 15. To our west as we head north on the freeway is the Great Salt Lake, the largest salt water lake in the Western Hemisphere.

In an average year, the lake covers about 1,700 square miles. It’s about 75 miles long by 28 miles wide with a maximum depth of 33 feet and an average depth of 14 feet. The size fluctuates due to its shallowness. As rains come and go, the lake gets bigger or smaller, but the depth doesn’t change much. The lake has ranged from a low of 937 square miles in 1963 to a high of 2,300 square miles in 1986.

In October 2021, the lake recorded its lowest water level in history due to a drought that struck the western region of the country. In March 2022, scientists reported the lake remained at historically low levels with predictions of further decline. In July 2022, concerns were raised about arsenic-laced dust being kicked up from the dry lakebed. In September 2022, it was reported the lake had once again dropped to the record low it hit in October 2021, prompting young climate activists to hold a wake on a portion of the now-dry lake bed.

In January 2023, a team of scientists warned that emergency measures need to be taken to prevent the lake from drying up due to excessive water use. The scientists said the lake’s ecosystem could collapse, exposing millions of people to the lake bed’s toxic dust.

In August 2023, it was reported the lake had risen more than 5 feet due to the record-breaking rains the previous winter. The lake, however, was still 4 to 5 feet below what’s considered healthy levels for its ecosystem.

In September 2023, a coalition of environmental groups filed a lawsuit, demanding that the state allow more water to reach the lake by allowing less water to be diverted for agricultural uses upstream.

In February 2024, officials announced that water will be released from the nearly full Utah Lake near Provo and sent to the Great Salt Lake to help raise its water levels.

In May 2024, it was reported that runoff from a heavy snowfall season in the mountains of Utah had helped restore some of the Great Salt Lake’s water levels, reducing demands for more water conservation.

In surface area, the Great Salt Lake is still the largest lake in the United States outside of the Great Lakes region.

The lake is the remnants of Lake Bonneville, a pluvial lake that covered most of western Utah and parts of Idaho and Nevada. That lake spanned 20,000 square miles, about the size of Lake Michigan and more than 10 times larger than the current lake. Lake Bonneville was formed about 30,000 years ago and existed until about 17,000 years ago when much of its water was released through the Red Rock Pass in neighboring Idaho during a yearlong flood.

The Bonneville Salt Flats west of the current lake are what remains of that prehistoric lake. The current lake emerged about 10,000 years ago.

The Great Salt Lake in Utah. Photo by Phys.og

Native Americans lived near the body of water for thousands of years. The first known European visitor was Jim Bridger in 1824. In 1843, John C. Fremont and Kit Carson were members of an expedition to the area.

The lake’s three main rivers and other tributaries deposit 2.2 million tons of salt into the lake each year. There are about 4.3 billion tons of salt in the lake now. The salinity on average is 12 percent, much greater than ocean water because there is no outflow, just evaporation. Swimming in the lake is similar to floating.

There are 11 islands in the lake, the largest being Antelope Island, a state park with a large bison herd, a number of campgrounds, an array of hiking trails and an expansive view of the lake. As you enter the northern edge of the park across the Antelope Island Road causeway, there’s the Island Buffalo Grill, a small restaurant that indeed serves buffalo burgers.

Not too far away is an historical marker dedicated to the silk industry in northern Utah. The industry began when Brigham Young ordered mulberry trees to be planted in the region to raise silkworms, who feasted on mulberry leaves. The grove on Antelope Island was planted in the early 1900s. The silk industry in Utah has disappeared, but the marker on the island is a reminder of its heyday.

Another historical marker along the lake is the Toelle Aviation Marker. The site is near the southeast corner of the lake just off Interstate 80. It consists of a 50-foot yellow concrete arrow laying flat on the ground pointing westward. The arrow is the remnant of a navigation system for airplanes that was in operation from 1924 to 1933 to help cross-country pilots, many of them delivering mail, find their way from place to place. At one time, there about 1,500 of the arrows between New York City and San Francisco spaced 5 to 10 miles apart. Radar systems made the arrows obsolete by the mid-1930s and there are only a couple hundred of them left. One of them is this one on Skunk Ridge not too far from the shores of the lake.

The Great Salt Lake has been called “America’s Dead Sea,” but it still provides a habitat for birds, brine shrimp and waterfowl but no fish. More than 7 million birds from 257 species either migrate through or live at the lake, including one-third of the world’s phalaropes and one of the nation’s largest populations of pelicans. Brine shrimp are the most populous animal in the lake.

The lake contributes an estimated $1.3 billion annually to Utah’s economy. About $1 billion of that comes from industry. Most of that is from salt and other mineral extraction, mainly from solar evaporation ponds used by five companies. The salt is not used for table salt but rather for salt licks, road salt and water softeners. Other minerals extracted include sulfate, magnesium and potassium.

Another $136 million comes from recreation. Yet another $57 million is from the harvesting of brine shrimp, which occurs during late fall and early winter. The lake produces 35 to 45 percent of the world’s supply of brine shrimp, which are mostly used as food for prawns.

——————————–

After less than an hour on northbound I-15, we enter the city of Ogden, a community of 87,000 that is 62 percent white and nearly 30 percent Hispanic or Latino.

The Fremont, Shoshone and Goshute tribes lived here from about 400 to 1350. The town was established in 1845 by trapper Miles Goodyear. It was the first permanent settlement in Utah of people of European descent and named after Peter Skene Ogden, a brigade leader of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Mormon pioneers initially helped populate the town, beginning in 1847.

Agriculture was main industry at first, but things changed after the Transcontinental Railroad was finished in 1869. The town developed into a major railway hub with nine rail systems, giving it the nickname of “Junction City.”

The town prospered so much that it at one time it had more millionaires per capita than any other U.S. city. In addition, the town was so wild during 1920s prohibition that gangster Al Capone actually left.

Rail service has declined after World War Two. The economy today is buoyed by federal, state and municipal governments. The IRS also has a large facility here with 5,000 employees.

One of the town’s other large employers, Chromalox broke ground in October 2023 on a $58 million, 100,000-square-foot expansion of its Ogden plant. The company manufactures electric heating systems. The project is expected to be completed by early 2025.

The town is also the site of the Business Depot Ogden, a 1,118-acre business park on former Army depot land.

The city has also spent $6 million to renovate the Ogden River Parkway. Ogden is known as an outdoor mountain town with skiing, biking and hiking.

The Osmond family grew up in Ogden with a strict Mormon upbringing before moving to Los Angeles in 1971.

Shuttles and Railroads

Our travels continue north on I-15 for another half-hour until we reach Brigham City, a town of 20,000 that rests at 4,439 feet elevation.

You probably don’t have to guess who this community is named after. The town was established in 1851 and named after Mormon leader Brigham Young.

A peach crop was started in 1855 when a farmer returned to town with 100 peach stones. The city has had a Peach Days festival since 1904. The first crop of sugar beets was planted in 1891.

The area is also home to Morton Thiokol, the manufacturers of the booster rockets for the space shuttles. Thiokol’s Wasatch Division had 6,400 employees in 1986.

The Morton Thiokol Rocket Garden near Brigham City, Utah. Photo by Utah’s Adventure Family.

The shuttle manufacturing operation was at the company’s main plant in Promontory about 25 miles west of Brigham City. Morton Thiokol also produced automotive airbags at a plant in Brigham City with part of the Promontory plant also manufacturing propellant for the inflators in automotive airbags.

After the explosion in 1986 of the space shuttle Challenger, Thiokol was blamed for the booster rocket failure. The town was devastated. One 89-year-old engineer told the New York Times in 2016 that he tried to warn company officials of the sealant issues in cold weather, but he was ignored.

Eventually, the company split into Morton and Thiokol, with Morton retaining the airbag business. Thiokol also had a plant in Brigham City at the north end of town but quit using that facility about 30 years ago and sold it about 20 years ago. Over the years, Thiokol went through various mergers and acquisitions. It’s now Northrup Grumman.

Morton eventually sold the airbag manufacturing business to Autoliv ASP, a Swedish company that still operates the airbag business both at the plant in Brigham City and at the Promontory site.

Today, there remains a Northrup Grumman plant manufacturing rockets at Promontory and an Autoliv ASP factory manufacturing automotive airbag components at Promontory and in Brigham City.

There is also a Morton Thiokol (ATK) Rocket Garden northwest of town that commemorates the company’s work on the shuttle program. The park contains 40 examples of military and supersonic hardware, including a solid fuel rocket booster for the shuttle program.

———————————

Not too far outside of Brigham City is a 43-foot-high golden spike looming over Interstate 15. The monument arrived in Utah in October 2023 and will used to point travelers to Highway 13 west in the direction of a historic site in our country’s westward development.

We take that highway and after a few minutes, we pass through Corinne City, a town of less than 850 people along the northeast edge of the Great Salt Lake that is a historic lesson in power politics.

The original town of Corinne was founded in 1869 by former Union soldiers and non-Mormons along the Union Pacific railroad line. It was named after one of the founder’s daughters.

The plan was for the community to be the freight transfer point for goods to mining towns in western Montana. In its heyday, Corinne had 1,000 residents, none of them Mormon, and 500 buildings. It was known as the “Dodge City of Utah” because it had had 28 saloons and 16 liquor stores. It was called “Gentile Capital of Utah.”

Brigham Young didn’t like what he saw here. So, he built a railroad line in 1877 that went directly from Ogden to Idaho and Montana. Those tracks bypassed Corinne and assured the demise of this upstart community as suppliers abandoned the town’s wagon service for rail transport.

The town’s population declined and Mormon farmers moved in and made Corinne another LDS settlement. Today, the community remains a quiet, farming community.

——————————————

From Corinne City, we really get off the beaten path by taking Highway 83 west and then some two-lane roads. In a half-hour, we’ve reached Promontory Summit.

This is the place where the “golden spike” for the Transcontinental Railroad was ceremoniously hammered into the ground in 1869.

The railroad tracks no longer pass through here. There’s no town or highway. All that’s left is a national park with a visitors’ center, an engine house and a marker where the golden spike was sunk into the ground.

The transcontinental project began in 1862 with the Pacific Railroad Act. It was approved only because Southern states had seceded and couldn’t vote against it.

Central Pacific workers started in 1863 in Sacramento, using mostly Chinese workers. Union Pacific laborers started in 1865 in Omaha, Nebraska, using Irish immigrants and Civil War veterans. The workers battled through bad weather, rough terrain and attacks by native tribes.

A reenactment of the 150th anniversary of the golden spike ceremony for the Transcontinental Railroad was held in May 2019 at Promontory Summit in Utah. Photo by the Los Angeles Times.

On May 10, 1869, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific tracks finally met at the 4,900-foot-elevation Promontory Summit after laying down 1,776 miles of rails. The site had been selected in April by Congress. The original date was May 8, but that was delayed two days by a pay dispute with rail workers.

On that day, the Union Pacific’s No. 119 locomotive and the Central Pacific’s No. 60 were brought together, face to face, separated by only a single railroad tie. A ceremonial gold spike was driven in first, then removed. Three spikes of gold, silver and gold/silver were then pounded in. The event was billed as the “wedding of the rails.” In 1898, the ceremonial gold spike was donated to the Stanford Museum in California, where it remains today.

A direct coast-to-coast rail journey on the railroad didn’t actually occur until 1873. The railroad route reduced cross country travel from months to one week and cut costs from $1,000 to $150.

The railroad across Promontory Summit was in use for 35 years. However, Central Pacific and Union Pacific built a railroad trestle across the Great Salt Lake between 1902 and 1904. The 102-mile Lucin Cutoff bypassed Promontory. The final scheduled transcontinental train passed through Promontory on September 18, 1904.

After the Great Depression, the railroad decided to end its service through Promontory. An “unspiking ceremony” was held on September 8, 1942 to lift out the old steel rails.

The Golden Spike National Historic Park was established in 1965. Its 2,735 acres is administered by the National Park Service. The park now has a visitors’ center and an engine house with walking trails and auto driving tours. The golden spike site is 100 yards from the visitors’ center. The site receives 60,000 visitors in a typical year.

A celebration in May 2019 of the 150th anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad was held. There were also calls to remember the Chinese immigrants who were vital to the building of the line.

The importance of railroads to the growth of the United States is difficult to overstate. The industry’s crucial contributions to the country are discussed further in a special report on the 60 Days USA website.

Falls, Canyons and Jumps

We have a 2 ½ hour drive ahead to reach today’s final destination.

So, we reverse course on the two-lane roads and head back to Highway 83. We roll north on that roadway until it hits Interstate 84, a freeway we will see a lot of tomorrow.

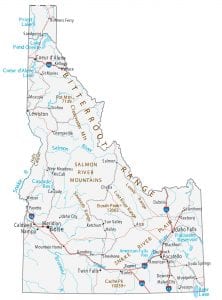

We continue north and in a little less than an hour after leaving the golden spike memorial we cross back into Idaho, the fifth state that we’ve entered more than once on this journey.

I-84 takes us through south-central Idaho until it bends sharply west at its juncture with Interstate 86. From there, it’s a straight shot to Twin Falls.

A few miles before we get there, we come upon Shoshone Falls, a waterfall on the Snake River that is sometimes called the “Niagara of the West.” The falls are 212 high feet, 45 feet higher than Niagara Falls, as its water flows over a rim 900 feet wide. As much as 20,000 cubic feet of water flows over the falls per second.

Local officials say the best viewing is in the spring after the snow melt and before summer water diversions. The Snake River water that is diverted 20 miles upstream helps irrigate 500,000 acres of farmland that produce crops worth $62 million annually. The falls also produce hydroelectric power.

This water wonder was formed about 14,000 years ago about some severe flooding. Explorers documented the falls in 1860s and it became a tourist attraction in the 1880s.

A few miles west of the falls is a historic spot in the world of stunt driving. In 1974, daredevil Evel Knievel attempted to ride his Skycycle X-2 across the wide canyon here formed by the Snake Rover. The jump failed after a parachute malfunction. The dirt ramp used by Knievel is still here, although it’s on private property. A plaque honoring Knievel was dedicated in 1985 at a bridge where we are headed next.

———————————-

There aren’t any waterfalls within Twin Falls itself, but it has a spectacular canyon cut by the Snake River and a classic bridge that crosses the gap.

The Snake River Canyon forms the northern boundary of the city limits. The canyon ranges from 500 feet deep to a quarter-mile wide and runs for about 50 miles.

The four-lane Perrine Bridge spans the canyon. It’s a truss arch span about 1,500 feet in total length with a 993-foot span between springings with a deck height of 486 feet over the Snake River. It’s the fourth highest arch bridge in North America and eighth tallest bridge in the country. The deck is also 3,600 feet above sea level.

The Perrine Bridge over the Snake River in Twin Falls, Idaho. Photo by Gribblenation.

The original bridge opened in 1927. The current bridge opened on July 31, 1976, which coincidentally is the day my wife, Mary, and I got married. The original bridge was dissembled afterward. The current bridge is the only place where BASE jumping is legal all year without a permit. The jumping was legalized in the late 1990s.

At least four jumpers have died since 2002, but that doesn’t dampen the enthusiasm of the thrill seekers who come here. When Mary and I visited in 2017, we saw jumper after jumper leap from the bridge and parachute their way to the canyon below, much to the delight of the large crowd that was watching.

The river has always been an important part of Twin Falls.

The first European visitors came through about 1811, an expedition led by Wilson Price Hunt to find an all-water route from St. Louis to Astoria, Oregon. At that time, the area was a neutral zone between U.S. fur trappers and British fur trappers with the Mexican border just 50 miles south.

An 1870 gold rush brought some settlers, some of whom stayed and farmed. The Oregon Short Line Railroad arrived in the early 1880s. In 1903, I.B. Perrine established the Twin Falls Land and Water Company to build an irrigation canal for the region. In 1905, Milner Dam was constructed, along with irrigation canals that made the region agriculturally viable.

Twin Falls was founded as a planned community in 1904 and incorporated as a city in 1907. In the original town design, streets were built in a northeast to southwest and a northwest to southeast direction to accommodate sunshine, the wind and irrigation. The NE-SW roads were numbered and called streets. The NW-SE roads were numbered and called avenues. Only Main Avenue and Shoshone Street had actual names. In 2003, the numbered streets (but not avenues) were re-named to avoid confusion.

After Milner Dam was built, agriculture in south-central Idaho expanded. Twin Falls became a main economic center for the region and has held that distinction to today. The city has been a major processing center for products, in particular beans, hay and sugar beets.

Base jumping is popular for both daredevils and spectators at the Perrine Bridge in Twin Falls, Idaho.

In the past few decades, Twin Falls has diversified its economy. Glanbia Cheese and the Jayco Inc. recreational vehicle manufacturer are two of the newer employers. Chobani yogurt operates the world’s largest yogurt manufacturing plant in Twin Falls. The factory underwent a $20 million expansion in 2017. In 2019, the company opened a 71,000-square-foot innovation and community center on the grounds.

In recent years, Twin Falls has become more multi-cultural with Hispanic and Latinos representing 15 percent of the city’s 56,000 residents. Syrian refugees began arriving in 2015.

The assimilation, however, has made Twin Falls a target.

The Refugee Center at the College of Southern Idaho were harshly criticized by hate groups in 2017 for taking in refugees from the Muslim world. Russian groups were accused of putting together an anti-immigrant ads on social media and organizing anti-immigrant rallies in Twin Falls. Chobani has been attacked by right-wing activists for hiring refugees.

However, the Refugee Center and the city have fought back.

In 2017, refugees who have settled in Twin Falls discussed how welcoming the community has been. In 2019, the High Desert News reported on how the refugee center has thrived despite the political criticisms. In 2019, the members of the City Council also signed their names to a letter supporting the resettlement efforts at the Refugee Center.

In 2020, officials at the center, which opened in 1980 and has helped resettled 2,500 refugees, said they continued to provide full services despite budget cuts due to the support of the community. In October 2021, the center welcomed the arrival of refugees from Afghanistan who fled their country after the Taliban took control.

Tomorrow, we will be on the move again as we head out of Twin Falls and travel west and then north to visit a human rights memorial, a town known for its popular shirts and a harbor that has one of the nation’s largest inland ports.